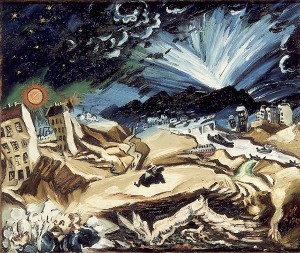

A cold wind blows tiles off of roofs and hats off of heads. The first pages of Robert Schindel’s new novel Der Kalte (The Cold One), read here by the author, are stormy. The Austrian novelist, poet and essayist born in 1944 already won over his readers with his persuasive images and poetic language in Gebürtig (Born-Where), published in 1992. Here too, the atmospheric beginning is reminiscent of the first line of the expressionist poem “Weltende” (End of the World): “From bourgeois’ pointed heads their bowlers flew, the whole atmosphere’s like full of cry” (Jakob van Hoddis).

Apocalyptic Landscape by Ludwig Meidner, 1913

© Ludwig Meidner-Archive, Jewish Museum Frankfurt-am-Main

Yet in the first scene of Schindel’s novel a world unfolds: Vienna of the Waldheim affair, from 1985 to 1989. During the 1986 Austrian election campaign, a debate ignited around the conservative candidate, Kurt Waldheim, who was indicted for war crimes. In his autobiography, he had concealed his time as a Wehrmacht-officer. Represented in the novel by the figure Johann Wais, he professes “that he had done nothing that one hundred thousand other Austrians had not done, too.” This is precisely why he functions “as an involuntary clarifying machine.” The prototypical Austrian, who would have liked to be a proud executor of duty yet never more than a spectator, and, actually ‘Hitler’s first victim,’ rallied artists and intellectuals constituting “the other Austria” against him. Accordingly, theatre and literature play an important role in the novel, in particular the Viennese Burgtheater, which, led for the first time by a German director, sparks controversies by staging political plays. Schindel also picks up on historical debates surrounding the anti-fascist monument in Vienna.

The author helps himself to the ‘quarry of history.’ But he constructs autonomous characters, who emancipate themselves from their historical counterparts and function even without knowledge of their political referents. Surrounding the literary renditions of Waldheim, Peymann and Hrdlicka, as well as Simon Wiesenthal are a large number of other figures who are not based on any specific historical model. The Jewish fighter in Spain and survivor of Auschwitz, Edmund Fraul, and his wife Rosa, who is also a Jewish survivor, convey the historical experience of ‘surviving’ as being a matter not settled once and for all. Rather, their challenge is to “continue to live” (weiter leben, as formulated in the title of Ruth Klüger’s autobiography, which was translated into English as still alive). This pertains in particular to their encounters with former tormentors, who had been acquitted or had received only short sentences. The emotional and climatic coldness surrounding the eponymous protagonist seizes the readers and provides a vivid image for the consequences of Auschwitz, as do the “quagmires of thought” and “anthills under skullcaps,” which haunt the married couple in their sleep.

In an unusual, moving, yet blunt description, Fraul opens his armor of coldness upon meeting, of all people, the former concentration camp overseer Rosinger, and ends up crying “tears of ice.” Though Rosinger also suffers from insomnia, the novel is careful not to blur the line dividing perpetrators from the persecuted. The past is made immediate when “both residents of Auschwitz” tell one-another stories “about our home” from their diverging perspectives.

The novel’s present is told with much humor and via a large number of viewpoints. Since many figures act as first-person narrators, each chapter arouses a tension as to who is speaking. Much of the large cast of characters work in arts and politics, but some are cardiologists, as befits the theme of emotion. Various generations, genders and standpoints are represented within the landscape of memory – which is at times better described as a landscape of forgetting. Yet the characters are not confined to specific types. On the contrary, only few novels equip their figures with the amount of desire for love and life as Robert Schindel’s. The young Dolores, who adorns her voluptuous neckline with a Star of David, for instance, is a counterweight to her painful name. As Stephan, her non-Jewish boyfriend, notes in his diary, she is passionate in bed and invites him to a “merry celebration” of Pessah. The figures, and with them the readers, at times lose oversight in the midst of erotic desire, bringing the novel closer to life than any conceivable sociological categorization. The author appears to love his figures; even Johann Wais is portrayed with a certain amount of sympathy.

More than six hundred pages offer ample “nutritious letter-dishes.” Along the way, the readers re-encounter acquaintances from Gebürtig and, by the end of the novel, forge ties with new ones. Since Schindel recently spoke of a trilogy, there is good reason to hope for a sequel by this artist of narration and language.

Mirjam Bitter, Media