in Conversation with Emile Schrijver, Curator of the Braginsky Collection

What made you decide to be curator of a manuscript collection?

When I studied Hebrew in Amsterdam, a lecturer took us to see the University of Leiden’s collection of medieval manuscripts. In the impressive vaults, I saw ancient manuscripts for the first time: the only manuscript of the Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi), for instance, and one of the earliest Rashi manuscripts. Seeing these ancient sources, and gaining first-hand experience of living history, was overwhelming. Historical books had a strong effect on me. I subsequently studied at the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, the Jewish library at the University of Amsterdam, where I later began to work. A few years ago, Mr. Braginsky was looking for a curator for his first exhibition in Europe. Mutual acquaintances from the international circle of manuscript specialists put us in touch with one another. We got along well and were soon able to establish a good, trusting working relationship

What do you do as a curator of the Braginsky Collection?

I take care of the collection. I am responsible for Mr. Braginsky’s new acquisitions and for his existing objects. Most new acquisitions are delivered with a short description. Others we describe and photograph, before adding them to our inventory. I carefully examine the books’ condition and, if necessary, commission their restoration. I’m also responsible for monitoring the climate in the storerooms. Inquiries concerning exhibitions and reproductions are a lot of work for us. The process of digitizing our stock is ongoing. Occasionally, scholars wish to view specific works at length. We also organize presentations on our own premises, on behalf of the European Association of Jewish Museums, for example. Public relations for events such as the Jewish Book Week in London in 2013 likewise require a great deal of preparation.

What makes the Braginsky Collection so special?

The way it has grown is remarkable.—When he started out, Mr. Braginsky was motivated by nothing more than to purchase beautiful books. His choice of consultants, as the collection reveals, was excellent. Art dealers soon became aware of Mr. Braginsky’s interest in high quality documents. And they helped him pursue his focus for many years, leading, for instance, to the acquisition of the Herlingen Collection now in his possession, which is a distinct chapter of the current exhibition,“The Creation of the World” That is one strongpoint of his collection; another is the breadth of its thematic content. Given the range of his acquisitions, which include manuscripts from India, Eastern Europe and Iraq, Mr. Braginsky has made his way – as I like to say – on a journey through Jewish worlds.

Some manuscripts have strange names, such as the “Second Braginsky Herlingen Haggadah.” Why?

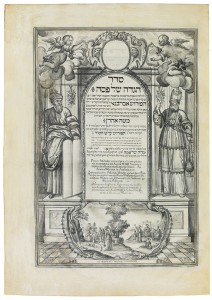

Front page of the Second Braginsky Herlingen Haggada © Braginsky Collection, Zürich, photo: Jens Ziehe

I asked myself this question several times when I was a student. Once you work for a collection, you find yourself having to name books so as to be able to tell them apart at a glance. Mr. Braginsky had one Herlingen Haggadah, which we called the Braginsky Herlingen Haggadah and which we displayed in our exhibitions under this name. Then he bought a second Herlingen Haggadah. We called it the Second Braginsky Herlingen Haggadah according to the convention of naming books after their owners so that they can be clearly identified—it’s convenient that way. When manuscripts become known under a certain name, the name often persists, even when the manuscripts change hands. That is the case with the Harrison Miscellany, for example, which we exhibit as part of the Braginsky Collection.

Please tell us about one interesting object.

This small Latin Herlingen micrograph showing King David playing the harp illustrates how artists depend on the market and collectors in order to become artists. It was purchased from an anonymous owner about seven years ago for very little money, in essence because the frame was so beautiful; yet it was able to be sold at auction shortly afterwards at a much higher price because someone had recommended that the first buyer have Sotheby’s evaluate the manuscript.

We are speaking in German, your native tongue is Dutch, and you studied Hebrew. Which other languages do you speak and which do you use in your work?

I speak English and German best of all. I studied Hebrew and Aramaic at university, as well as Syrian, Phoenician, Ugaritic, and Akkadian. I speak a little Latin and can also read the relevant literature in my field in French, Italian, and Spanish. I no longer use the ancient Semitic languages so much but do have to switch constantly from one modern language to another. I also make regular use of Hebrew, Yiddish, Aramaic, and sometimes a little Latin.

Miriam Goldmann, Project Manager of the Exhibition

“The Creation of the World”