Signe and Darrell have been together a long time. They met in the USA, have shared an apartment in Berlin for nearly 15 years, and now have two daughters and a son together. Signe’s family is Jewish American on the mother’s side, German Protestant on the father’s. Darrell is 100 % North American – in his family, you can find just about everything: Puritan pastors, Unitarian ministers, Mormons, Catholic liberation theologians, liberal Muslims, secular Jews. I talked with the two of them about circumcision and the role that Jewish tradition has played in raising their children.

You first had a daughter, then twins. One of the twins is a boy. Did you think a lot about the question of whether to circumcise your son while you were pregnant?

Signe: When I found out that one of the twins was going to be a boy, my first thought was: “uh-oh – now I’ve got to deal with the question of circumcision!” I felt – and still feel – a certain ambivalence on the subject. We spoke about it a few times pretty seriously.

Darrell: As I remember it, this never became a big issue – at least not for me, or between Signe and me. Had Signe insisted on circumcision, I think I might have let myself be persuaded. After all, I am circumcised, too. For me – or rather for my parents – the decision was not based on religious considerations. Circumcision was simply the norm at hospitals in the USA. In Germany today, it isn’t.

Signe: I had inquired early on whether there was someone in the hospital who would be able to carry out the circumcision right after he was born. It turned out that they don’t offer that. So I put together a list of doctors who could do it within eight days of the birth.

So it was clear that the circumcision – even if not performed according to Jewish ritual – should be carried out by the eighth day?

Signe: If we were going to do it, we should do it right. But there’s a practical reason for that, too: within eight days of the birth it can be done without anesthesia.

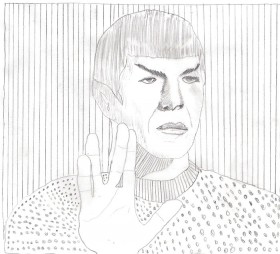

…the sign of the priesterly blessing.

Vignette by Ephraim Moses Lilien © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jörg Waßmer

So what ultimately made you decide not to do it?

Darrell: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Circumcision would have meant performing a surgical operation that was not required by any specific health condition. So why do it?

Signe: You have to have a pretty strong religious feeling to not feel that way. I asked myself whether I could really make the irreversible decision for my son to be marked with the sign of belonging to the Jewish faith – and if not, why not? But in the end, we can’t foist on our children affiliation with a religious community, when we ourselves don’t live that way. On the other hand, I know that means we are passing our own rootlessness on to them.

And how did you feel once the decision was made?

Signe: I was, to be honest, very happy about it. Not least of all because I also had the inexplicable – and from a feminist standpoint unjustifiable! – feeling that a father in some sense enjoyed greater sovereignty over the body of his son than a mother, at least with regard to this question. Had I insisted on circumcision, I would have been encroaching on that relationship.

Darrell: My mother was in favor of circumcision on account of the father-son relationship. She is not Jewish, but for her it seemed important that a son look like his father, and not different. But I wasn’t persuaded. I mean, he’s got blond hair – that’s much worse! I’ve never regretted our decision.

Signe: Me either. But I must admit – every time I changed his diaper, I thought: how weird that he’s not circumcised!

Back to the question of identity. If your resolve was not strong enough to decide that your son should bear the sign of the covenant and belong to the Jewish community, what do you say to him now when he asks: “Am I Jewish? Am I Christian?”

Signe: Ah, you know what? I work in the Jewish Museum, our younger daughter is playing Maria in the Nativity play at her nursery school, we light candles at Hanukkah, and march in the Lantern Parade on St. Martin’s Day. On November 9, we came across some people who were polishing the memorial stones planted along our street in memory of those who died in the Holocaust. My elder daughter asked me then for the first time: “would they have killed you, too, Mom?“ So we talked for a long time about war and various forms of hatred. That is a subject of deep concern for her, at the tender age of six. I think our children will negotiate their identities through a series of issues we could never plan in advance.

Darrell: We try to question borrowed identities whenever we can. The school environment is sure to reinforce them, though. I’m sure we’ve got a lot of discussions like this ahead of us.

Signe: I agree – but if our son decides he wants a Bar Mitzvah when he turns 13, he’s going to hate us!

The interview with Signe and Darrell was conducted by Mirjam Wenzel, Media