— the Hanukkah Message?

Mice with a vice

Photo: CC-BY Michal Friedlander

I have been using the same Hanukkah lamp for nearly 20 years. I find it aesthetically-challenging and totally impractical: it is difficult to clean and the candles fall out. Yet I persist in using it because it provokes me to think. When I put the illuminated, figurative lamp on the windowsill to publicly “proclaim the Hanukkah miracle of light,” the same three questions always resurface in my mind: “Who designed this lamp?,” “What were they thinking?,” and, “Are Mickey and Minnie Mouse actually Jewish?”

The scene never changes. According to the mantle clock it is 12:12 (a.m. or p.m.?) and Mickey and Minnie are cozily positioned in front of a redbrick fireplace, where a log fire blazes. They are happily ensconced in a round of the dreidel game, which is typically played during the Hanukkah holiday and is an evolutionary form of an old German gambling game, which involved a spinning top. In this Jewish version, Hebrew letters are written on the four faces of the top, denoting how many pieces can be won from the pot. The ante pieces may be plastic chips, pennies, buttons, nuts or candy, according to family tradition. Rabbinic tradition, in turn, has given the Hebrew letters a symbolic, theological meaning relating to the festival.

In the Mouse household, the stakes are high and the booty is lined up in front of the players. There are towers of silver and gold coins, two big bags (evidently holding more coinage) and three half eaten chocolate coins lying on the parquet. This show of wealth is framed at each end with an unopened, wrapped gift. The presumable meaning of this scenario is that Mickey and Minnie are staying up way past their bedtimes and have been given unlimited access to chocolate coins, a wish not uncommon among Jewish children.

A “Hanukkah gelt” coin purse, find out more in our German-language online collection’s search

Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

While it is customary to give children money on Hanukkah, the precise origin of the custom is unclear. It is known from centuries past that parents gave their offspring money to distribute to their teachers during the holiday and the wealthy gave financial donations to help support Torah students. Chocolate “Hanukkah gelt (money)” became popular in the USA when foil-wrapped chocolate coins first made an appearance there in the 1920s and are still beloved today. The meaning of Hanukkah monetary gifts is a matter of interpretation: some consider it an opportunity to teach children about giving charity, others view the coins as a symbol of freedom. In the story relating to Hanukkah, the Jews free themselves from an oppressive regime and minting coins can be seen as a mark of independence.

However, if we step back from these layers of Jewish interpretation and look at my Hanukkah lamp again, what do we see? The dominant motifs are mice (friendly, Jewish vermin) and money; the prevalent themes appear to be consumption and the acquisition of wealth. We live in an age in which the stereotypical association of Jews and wealth is still perpetuated and reinforced.

“Lucky Jew” or pastoral idyll? The Poznań market panders to consumer tastes.

Photo: CC-BY Noam Friedlander

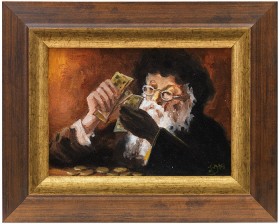

During a recent trip to Poland, I bought a “Żydki” painting for the Jewish Museum Berlin collection, after much consideration. I was wandering through a street market in a small town and discovered a huge selection of miniature paintings and prints showing stereotypical figures of bearded, male Jews, counting money. I walked away from one stall three times before I finally took a deep breath and exchanged my złotys for an original work of dubious artistic quality. Such images (and figurines) are produced today for the general Polish public who view them as good luck charms that bring prosperity. These pervasive representations hang in shops, restaurants and of course in private homes.

Hang this picture upside-down (in Poland), and it will rain prosperity.

Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

In Poland, non-Jews mostly perceive them as charming objects of local folk art. From the viewpoint say, of a Jewish-American tourist, the stereotypical representations scream of anti-Semitism. The dual convictions, from different cultural contexts, co-exist uncomfortably. The Polish images travel to new destinations with every tourist’s purchase and are placed on display in public and in private, just like my Disney lamp. Let’s not underestimate the visual power and impact of messages broadcast by seemingly harmless objects.

Michal Friedlander is Curator of Judaica and Applied Arts and her most recent museum acquisition is a Yoda Lego Mezuzah. But that’s another story.

P.S. For a riveting study of Polish “Lucky Jews” see the book of the same title by Erica Lehrer, Cracow, 2014. http://www.luckyjews.com/introduction/