Workshops for young refugees

What’s written in a Jewish marriage contract? As a minority, how do you secure your civil rights? And why is Hanukkah celebrated for eight days? My work as a guide at the Jewish Museum isabout how to coax stories from objects on display — but also about language. The first thing I did when I began working here about four years ago was to look up how to say “ruminants with cloven hooves” in French. You need to have this phrase at the ready if you want to explain Jewish dietary laws to a group of French museum visitors. My French didn’t help much, however, when I led the first workshops in August of 2016 for Welcome Classes. At this time I was to organize workshops for young people whose German was still at a very basic level: “A1” as their teachers told me. “A1” — what did that mean? That didn’t tell me much, though soon I discovered that it meant these students didn’t know words like “candles” and “holiday” in German. I turned to the few Arabic words I knew.

Young refugees write their names on t-shirts that they take home with them after the workshop; photo: private

My mini-dictionary offered up “yahud” (Jew), “Al-Quds” (Jerusalem), and a few polite phrases like “hello”, “bye”, and “thank you”. In addition I employed a lot of gestures and facial expressions to communicate certain activities, such as lighting candles and writing on Torah scrolls. Sometimes I was frustrated, imagining that participants would have been more talkative during the workshops if we’d had a common language. The teenagers would certainly have been able to follow longer discussions about subjects like architecture and history in their mother tongue.

I conducted two special workshops for Welcome Classes last year: the baking workshop where we prepared traditional Shabbat breads, and the t-shirt workshop during which students printed Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin letters onto white tees. I usually led the young refugees through the permanent exhibition, focusing on a topic like “Shabbat” or “Hebrew”. Then they would have the chance to get creative themselves: either they would bake challah buns as one does to prepare for the Jewish day of rest, or they’d print their names in Hebrew lettering on t-shirts.

For the practical part of the workshops, the language barrier was clearly much less important. Instead of explaining how you braid the dough, I would simply demonstrate it and the kids then had no problem making their own yeast buns. I didn’t even have to ask them to tidy up after the baking was finished: they grabbed the brooms and dishrags of their own accord. We could also pantomime the 39 activities forbidden on Shabbat (the melachot); in fact that’s a component of the workshop anyway. Plus, I would have a children’s book with illustrations depicting these various prohibited forms of work. Nonetheless some more complex ideas — for instance, that the reception of the Shabbat is often compared with the visit of a queen in your home, thus you prepare your apartment accordingly — were presumably lost on our young visitors, given the necessity of verbal explanation.

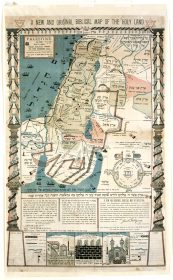

Jacob Goldzweig, Biblical map of the Holy Land; Jewish Museum Berlin, Löwenhardt-Hirsch Collection, acquisition with funds from the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

I imagined the Hebrew workshop as a potential area of conflict since Hebrew is of course primarily spoken in Israel, a country regarded with some reservations by its Arab neighbors. And because some of the youthful refugees came from these countries I was prepared for a degree of rejection. Instead, I was met with the pleasant surprise of children who much preferred to search for commonalities between Arabic and Hebrew than make political statements. Thus the emphasis was on, among other things, how both languages are written from right to left and some of the letters actually bear a resemblance. At some runs of the workshop we looked together at a map of the Middle East with Hebrew lettering on it. While the German students tended to need a couple of minutes to locate Israel and its neighbors, this activity turned out to be a game of “point out home” for the Welcome Classes: they all immediately recognized Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt and could name them.

The best experiences — what meant a lot to me, like the enthusiastic faces and students who tried hard, despite our language barriers, to communicate through international words such as “Islam” — occurred regularly in one small corner of the museum. It’s where short films are shown on the rituals of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

The Qur’an, the Prophet Mohammed, and the Islamic pilgrimage are mentioned, among other things. I remember one group of boys well. They’d seemed fairly bored at the start but when we got to that part of the exhibition, they stopped of their own initiative to watch the films twice through. I had to smile to myself, because they reminded me of another group of children: Christian kids (culturally-speaking) who had been drawn as if magnetically to stop in front of the Christmas tree in the section on family — searching, like the refugees, for the familiar in an alien setting.

Mirjam Beddig has been a guide at the Jewish Museum since 2013 and is happy to be able to give young people a little preview of Hebrew and see them grow curious about the language.