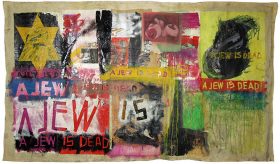

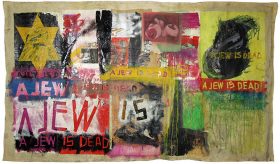

A Conversation with Peter Weibel about whether Boris Lurie Should Be Seen as a Part of the Ultra-realist Neo-avant-garde, and Pornography as a Metaphor for Capitalist Society

Boris Lurie, “A Jew is dead,” 1964; Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York, USA

Mirjam Bitter, blog editor: As part of the program accompanying our Boris Lurie retrospective, you’ll be giving a lecture at the Jewish Museum Berlin on 30 May 2016 on the subject of “The Holocaust and the Problem of Visual Representation,” (further details of which can be found in our events calendar). Is this tied up with the idea that the Holocaust is a major theme in Lurie’s work?

Peter Weibel

© ONUK

Peter Weibel: The Holocaust, along with war, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki were pivotal traumatic experiences for the post-Second World War neo-avant-garde. Take, for example, Yves Klein’s painting “Hiroshima” (1961) or Joseph Beuy’s environment “Show Your Wound” (1974–1975). Many artists responded to the inhumanity they had witnessed by calling into question humanity and indeed, civilization itself: Why, they asked, had literature, painting, music, and philosophy been unable to prevent this twentieth-century barbarism? → continue reading

The Tragic Fate of Shmuel Dancyger Z. L.

The family at the grave of Shmuel Dancyger; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Morris Dancyger

During a visit to my hometown of Calgary Alberta, Canada in the summer of 2014, I had the opportunity to meet with Morris and Ann Dancyger, both child survivors of the Holocaust. Morris Dancyger was one of the very few children to have been liberated by the Russians at Auschwitz on 27 January 1945. In the iconic footage of the children displaying their tattooed arms, four year old Morris is in the center of the picture. Ann Dancyger and her mother had miraculously survived an execution in 1942 near the town of Ratno where she was born, and spent nearly three years thereafter in hiding. After a nearly two year trek to Germany following the end of the war, she was able to come to Calgary where relatives lived. I had not known the Dancygers while growing up in the city, and although I had much later read about the tragic fate of Morris Dancyger’s father Shmuel, I was completely unaware that his wife and children had settled in Calgary. → continue reading

Film Historian Claudia Dillmann on the Artur Brauner Film Collection in Our Library

The German film producer and Shoah survivor Artur Brauner has kindly donated to our Museum twenty-one films on the subject of the Shoah and the Nazi era—you’ll find the complete list on our website. Today, the Museum acknowledges our great appreciation of this gift with a special event in the presence of Artur Brauner and his family.

Claudia Dillmann

Photo: Deutsches Filminstitut/Uwe Dettmar

Prior to the event we interviewed film historian Claudia Dillmann about Artur Brauner and the appeal of his film productions, in particular for a Jewish Museum. Ms. Dillmann is Director of the German Film Institute in Frankfurt Main and a renowned expert on Artur Brauner, and also initiated the online resource www.filmportal.de. She talked to us about Brauner’s interest in the victims of Nazi crimes, the balancing acts it has called for, his veneration of Romy Schneider, and the German public’s tastes.

Mirjam Bitter, Blog Editor: Ms. Dillman, in your opinion, how representative is our Artur Brauner Film Collection of Mr. Brauner’s entire production list?

Claudia Dillmann: The films that Artur Brauner has donated to the Jewish Museum are indeed representative since they constitute a pivot of his career—one very dear to his heart—namely an abiding commitment to exposing the Holocaust, not least because forty-nine of his own relatives also lost their lives then. He sees these films as his personal “legacy,” one he has been forging since the start of his career. They are dedicated to victims of the Nazi regime and constitute a cycle that in his view is still not complete. In them, he has continually explored new facets of persecution under the Nazi terror and of the traumata he lived through himself. → continue reading