Program Director Cilly Kugelmann on the Exhibition “NO COMPROMISES! The Art of Boris Lurie”

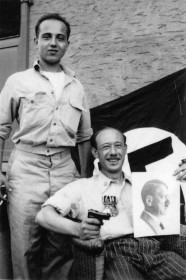

“As this image of Lurie with his brother-in-law Dino Russi from 1946 shows, the NO!art artists, in reclaiming the swastika symbol, robbed it of its symbolic value.” (Cilly Kugelmann)

Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York

Our major retrospective dedicated to Boris Lurie opens 26 February 2016 (for more information see www.jmberlin.de/lurie/en). Blog editor Mirjam Bitter spoke with Cilly Kugelmann about the artist, his provocative work, and the possible impact today of the taboos that he broke throughout his career.

Mirjam Bitter: What is your view of Boris Lurie? What sort of a guy was he? What distinguished him as an artist?

Cilly Kugelmann: The man and the artist Boris Lurie was shaped by his experience of persecution and concentration camps under the Nazi regime. And yet, unlike other artists who faced similar experiences, I feel he cannot be described as a “Holocaust artist.” With the exception of some early drawings from 1946 and a few paintings from the late 1940s, he neither chronicled these events nor sought to interpret the Holocaust artistically in his work.

Then what role did the Holocaust play in Lurie’s work? → continue reading

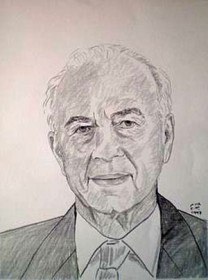

Remembering 4 November 1995

Twenty years ago today, 4 November 1995, Israel prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, was assassinated following a peace rally in central Tel Aviv. Mirjam Wenzel was there.

“It was a mild evening at Kikar Malchei Yisrael (Kings of Israel Square, now Yitzhak Rabin Square) in the middle of Tel Aviv, where throngs of people had gathered under signs of shalom achshav (peace now) to show their support for Rabin and Shimon Peres and their push for peace. The national religious movement had grown more hostile towards the government in recent weeks, and the media had been reporting its demonstrations with posters of Rabin in a SS uniform. No one could imagine, at least not within my circles, that this movement could turn deadly. From the Tel Aviv office of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, where I had a semester internship, the Oslo Accords were viewed as a political and economic fact. → continue reading

An Internet Harvest for the Day of the Refugee

“Refugees”, color woodcut by Jakob Steinhardt, 1946, purchased with funds provided by Stiftung DKLB. You can find this and other related objects in our German-language collection database.

This year’s Day of the Refugee takes place today, 2 October 2015 as part of Intercultural Week, with the slogan “Refugees Welcome!” We have taken this as an occasion to go through our own and other websites and blogs, gathering items on this subject. Since we work at a Jewish museum, stories about fleeing are part of our ‘everyday business’: practically all of the family collections given to our museum tell stories of persecution and flight, going beyond mere statistics to depict the fates of individuals. Letters, travel documents, photographs, and personal memorabilia tell of the desperate search for a country to emigrate to, failed or successful emigrations, the often difficult life in a foreign country, the search for relatives, friends, and former neighbors, now scattered across the entire world. We tell these stories in our permanent exhibition and they have also been the subject of various special exhibitions. At the moment, for instance, in our current cabinet exhibition “In a Foreign Country” you can see publications that originated in Jewish Displaced Persons Camps. Jewish men and women waited there for their passage to Palestine or later Israel, to the USA and other countries, where they hoped to start a new life after the Shoah.

In addition to our exhibitions, we also make stories of flight and displacement visible online, for example with a selection of objects: → continue reading