Singled Out and Viewed Suspiciously: Jews in the GDR

The history of Jews in the GDR did not begin with the country’s founding on 7 October 1949. Rather, from May 1945 onward, the course was set for the East-West division, the Cold War, the Stalinist purges, and the conditions of Jewish life in East Germany. At the same time, this period contained the seeds of a different course of history and other, unrealized options.

After World War II and the Shoah

When the war and the anti-Jewish persecution ended, an extremely heterogeneous group of Jewish survivors found themselves in the Soviet and the other three occupation zones in the destroyed and dismembered “land of the perpetrators.”

The survivors had been liberated from the death camps, fought in Allied armies, or returned from exile. Others had survived in hiding or been protected by non-Jewish spouses. Some initially saw Germany as a way station on the road to Palestine or the United States. Others deliberately returned to Germany, hoping to help shape a new society there.

Berlin, which was governed by the four occupying powers, was an important destination and hub for survivors and returnees. The newly constituted Jewish Community of Berlin had its headquarters in Oranienburger Strasse in the Soviet sector. Its first acting chairman was Erich Nelhans, he belonged to the then dominant group in the Jewish community who did not consider Jewish life possible in Germany after the Shoah and advocated emigration to Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish state there.

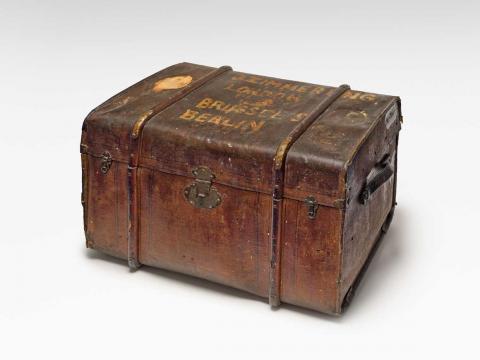

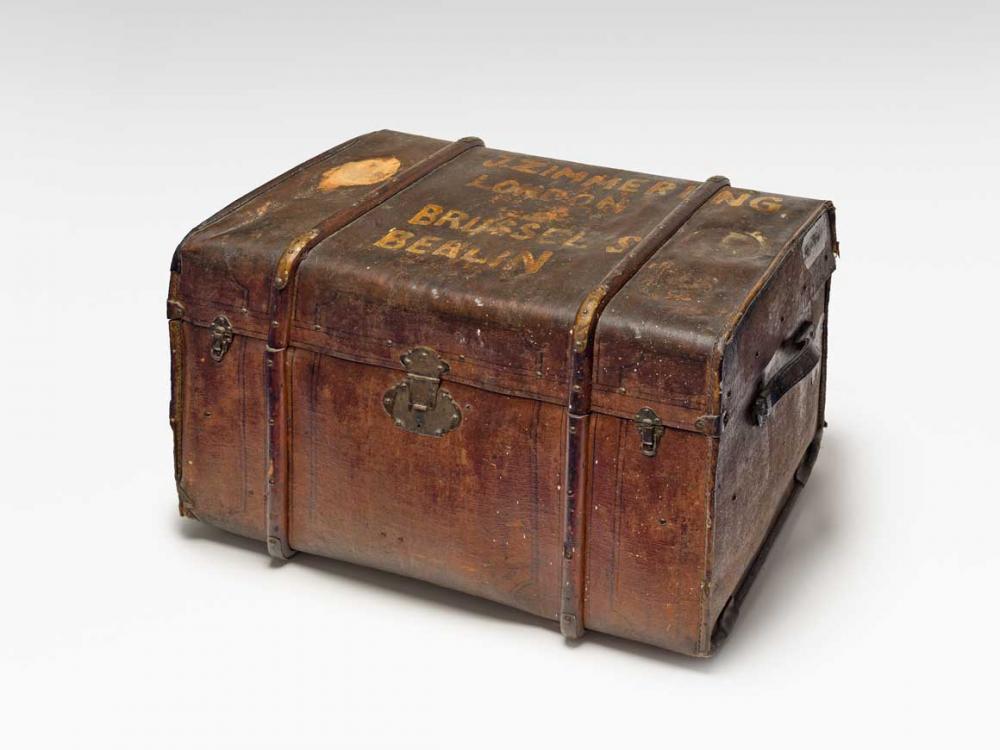

Josef and Lizzi Zimmering’s traveling trunk, probably Britain, 1930s to 1940s: both survived the period of Nazi tyranny in exile. After the GDR’s establishment, Josef Zimmering (1911–1995) became an important official in the new state; on loan from the Zimmering family, photo: Roman März

Nelhans also looked after Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe, tens of thousands of whom had fled to the West to escape postwar antisemitism in Poland. Many showed up at the Jewish community in the Soviet sector of Berlin, which directed them to the American and French sectors, where Displaced Persons camps had been set up. Nelhans attracted the attention of the Soviet intelligence service after helping Jewish Red Army soldiers escape to the West. He was arrested in his East Berlin apartment in March 1948 and sentenced to twenty-five years in prison by a Soviet military court. He died in the Dubravlag camp in Mordovia in 1950.

In the summer and fall of 1945, Jewish communities were established in several cities in the Soviet occupation zone, mostly at the initiative of Jews who had been spared deportation due to their non-Jewish spouses. In the weeks and months that followed, these Jews were joined by survivors from the camps and ghettos, refugees from Eastern Europe, and those who had emerged from hiding. Membership in these first few communities in Leipzig, Zwickau, Dresden, Chemnitz, Erfurt, and Magdeburg initially grew rapidly but then, starting in 1949, declined just as quickly. The smaller communities in Plauen, Mühlhausen, Eisenach, Jena, and other towns were dissolved between 1948 and 1953.

What were displaced persons?

After the Second World War, “displaced persons” referred to people stranded outside their countries of origin, including around a quarter million Jews in the western occupied zones of postwar Germany

New Beginnings

The attempt to reestablish Jewish life took place under contradictory conditions. The Soviet Military Administration and most regional governments in East Germany supported the founding or reconstitution of the Jewish communities and ensured that the returnees and immigrants received the basic necessities of life (a roof over their heads, clothing, health care, and additional food rations). At the same time, antisemitism was still rampant at the local authorities and in the population.

To meet the challenges of securing the daily lives of their members, representatives of the Jewish communities worked closely with the local committees set up to help the victims of fascism, which later became the “OdF” (victims of fascism) and “VdN” (victims of the Nazi regime) offices. Earlier, in summer 1945, the OdF committees, most of which were founded by liberated political prisoners, had initially opposed recognizing Holocaust survivors as “victims of fascism.” Their reasoning: while they “had suffered hardship, they had not fought.”1 Just a few months later, in October 1945, at the Leipzig meeting of the OdF committees from all parts of the Soviet occupation zone, this view was corrected. The reversal was primarily the doing of Julius Meyer and Heinz Galinski, who went on to establish the Department for the Victims of the Nuremberg Laws at the main OdF committee in Berlin.

Urgently needed support for the survivors also came from the Joint Distribution Committee (JOINT for short), a Jewish-American relief organization whose food donations and aid were distributed through the Jewish communities (from 1947 onwards, also through the Jewish communities in the Soviet occupation zone).

The Association of Victims of the Nazi Regime (VVN) was established in all four occupation zones in 1947/48. It initially defined itself as a nonpartisan interest group that represented all persecuted people. Jewish victims of Nazi persecution constituted a large group within the association and in Berlin even formed the majority. Although the distinction between “fighters” and “victims” remained contested in the VVN, cooperation between it and the Jewish communities initially went well, not least because many leading representatives of the Jewish communities held positions in the VNN.

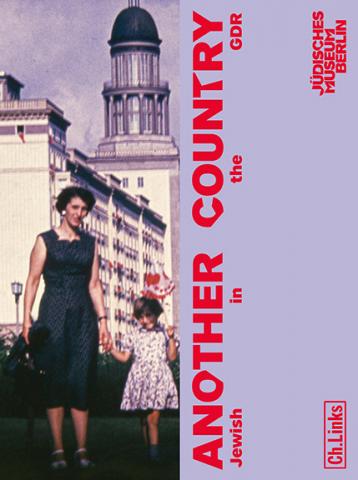

Exhibition catalog Another Country. Jewish in the GDR, in which among other texts you can find a more comprehensive version of this article; design: Team Mao, Berlin 2023.

The Cold War

With the separate currency reforms in 1948, it became clear that the four occupying powers in Germany would not act jointly to overcome the legacy of Nazism in Germany. The Cold War between the one-time allies and the founding of the two German states set new political priorities on both sides that led to the breakdown of the already fragile anti-fascist alliances.

In 1950, the West German branch of the VVN was classified as a “radical organization”

and monitored by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution. By contrast, the East German VNN continued to wield significant political and moral clout until it was dissolved in 1953. The eastern VVN provided representatives for parliaments, ran health spas, published several journals, and owned a publishing house. It influenced the drafting of a reparations law which included a special pension system and the preferential provision of health care, housing, commercial space, household products, and scarce consumer goods. However, it did not include a provision on the restitution of stolen property or on material compensation.

But the VVN’s initially postulated non-partisanship soon existed only on paper. Beginning in 1948, the SED gradually took control of the association’s governing bodies and began to subordinate all its activities to the new friend-or-foe mentality of the Cold War.

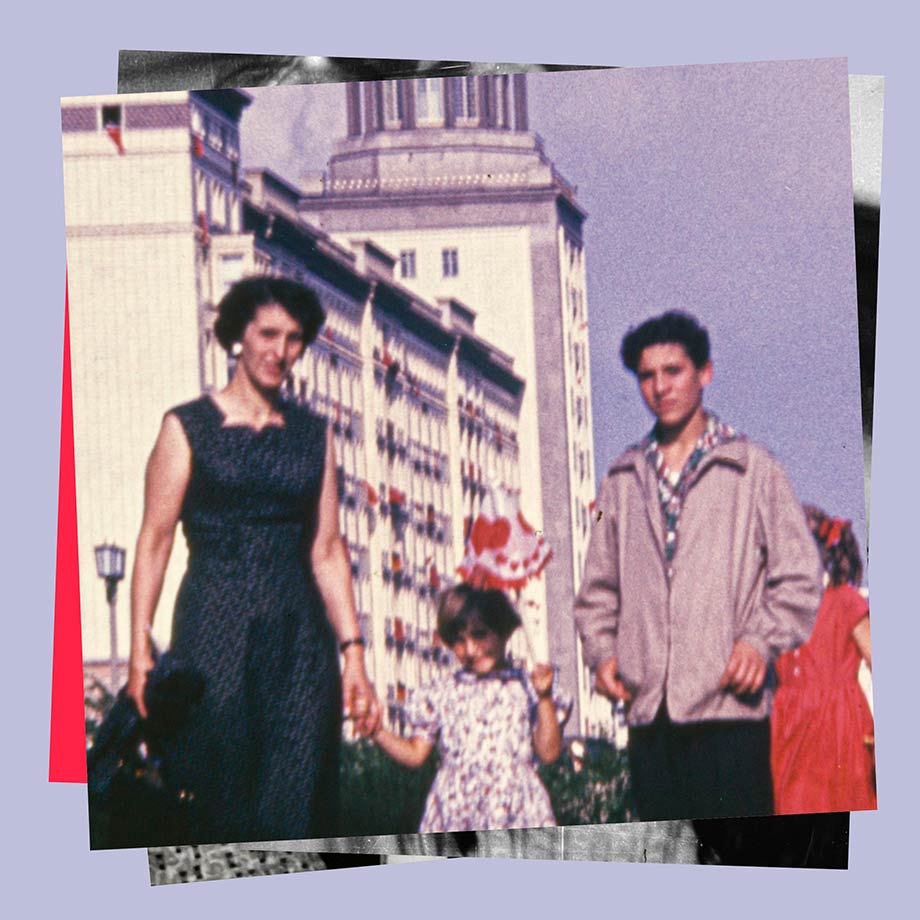

Alice Zadek with her daughter Ruth and her nephew David Hopp on Stalinallee (Karl-Marx-Allee), photographer: Gerhard Zadek, Berlin, ca. 1956; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Ruth Zadek. Gerhard (1919–2005) and Alice Zadek (1921–2005) returned to Berlin from UK exile in 1947. In the Soviet Occupation Zone and the GDR, the Zadeks were integrated into the political system from the start. However, as former emigrants to the West, they lost all their roles and positions in 1953.

Alice Zadek with her daughter Ruth and her nephew David Hopp on Stalinallee (Karl-Marx-Allee), photographer: Gerhard Zadek, Berlin, ca. 1956; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Ruth Zadek. Gerhard (1919–2005) and Alice Zadek (1921–2005) returned to Berlin from UK exile in 1947. In the Soviet Occupation Zone and the GDR, the Zadeks were integrated into the political system from the start. However, as former emigrants to the West, they lost all their roles and positions in 1953.

The Slánský Trial and its Consequences

With the start of the clearly antisemitic Stalinist show trial of Rudolf Slánský in Prague in late 1952, Jews in the GDR faced pressure on two fronts: first, they needed to defend themselves against continued and growing hostility from broad segments of the population, and second, they were subject to Stalinist antisemitism from the Soviet Union.

In early January 1953, Julius Meyer, SED member and President of the Association of Jewish Communities in the GDR, was pressured to “confess” his intelligence ties in interrogations with both the Soviet and the SED Control Commissions. They demanded that he surrender the lists of recipients of JOINT packages and persuade his Association to publicly distance itself from JOINT and to condemn Zionism. After the interrogations, Meyer traveled to Leipzig, Dresden, and Erfurt to warn leading Jewish community representatives of the impending persecution. Günter Singer, Helmut Salo Looser, Leon Löwenkopf, Fritz Grunsfeld, and Leo Eisenstädt fled to West Berlin that same day. Additional Jewish community members followed. Their exodus continued into the fall of 1953 amid antisemitic agitation in the media and under the influence of police searches of Jewish community offices and arbitrary measures taken by local authorities against recognized victims of persecution.

The suspicions and persecution were also aimed at state and party functionaries of Jewish origin who had no ties to the Jewish community.

Disintegration of the Jewish Communities

The events of 1948–53 and their consequences shaped the lives of Jews in the GDR until 1989. Most of the Jewish communities no longer had board members and also lacked rabbis and cantors. Membership had declined dramatically, caused not only by Jews fleeing the country. Fearing reprisal, many members of the SED had also left the Jewish religious community. The Berlin community split into an eastern and a western part. After Stalin’s death, targeted antisemitic persecution ended, but the accusations and suspicions were never officially withdrawn; they lived on beneath the surface in the form of fear and resentment.

With the forced dissolution of the Association of Victims of the Nazi Regime, which the SED Central Committee replaced with the Committee of Anti-Fascist Resistance Fighters, the Jewish survivors – like many other persecuted groups – no longer had a voice in politics. The Jewish communities could not fill this gap because they were essentially restricted to religious practice.

Due not only to the small number of members, but mainly to failed reparation attempts, the Jewish communities were completely dependent on state funds.

Remembrance Policy in the GDR

Until the mid-1980s, the topic of Jewish persecution and genocide played only a minor role at official commemorative events. The state’s remembrance policy focused on the communist resistance. Nevertheless, the crimes committed by the Nazis in the concentration and death camps were not taboo. School textbooks showed photographs of piled-up corpses in Bergen-Belsen and mentioned the mass killings in the gas chambers – though mostly without discussing their antisemitic background. The victims were described in general terms as “inmates from all European countries”

or were sweepingly attributed to the resistance.2

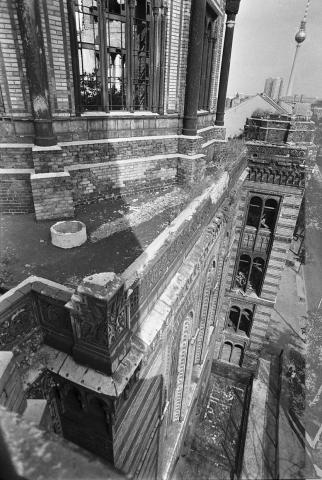

While in exile in France, Dora Davidsohn (1913–1999) worked for the Communist Party. She escaped the internment camp for “enemy alien” and joined the Résistance. Find out more about her and her first husband Alfred Benjamin in a video on our website. Résistance armband belonging to Dora Benjamin née Davidsohn, France, ca. 1942-1945; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Peter Schaul, photo: Roman März

For many years, commemoration of the 1938 November pogroms was limited mainly to the events in the Jewish communities, mostly accompanied by a brief newspaper note with a greeting from the SED Central Committee. The early 1980s saw changes to this well-rehearsed ritual, culminating in the major official commemorative event in 1988 marking the pogroms’ fiftieth anniversary. Members of the SED Politburo, all wearing kippahs and surrounded by TV cameras and flashing lights, lay wreaths in the Jewish cemetery in the Weissensee district of Berlin. The next day they lay the symbolic cornerstone for the reconstruction of the destroyed New Synagogue in Oranienburger Strasse. These actions were clearly motivated by foreign policy and economic interests linked to the GDR’s relations with the United States; however, state and party leaders were also responding to the shifting situation at home, where committed representatives of a generation that had grown up in the GDR were taking seriously their anti-fascist education and were no longer willing to accept the ignorant, negligent treatment of the traces of former Jewish life in their surroundings. Their initiatives to restore destroyed and neglected burial sites and to study Jewish history in their cities and communities suddenly met with interest and were even promoted by the local authorities.

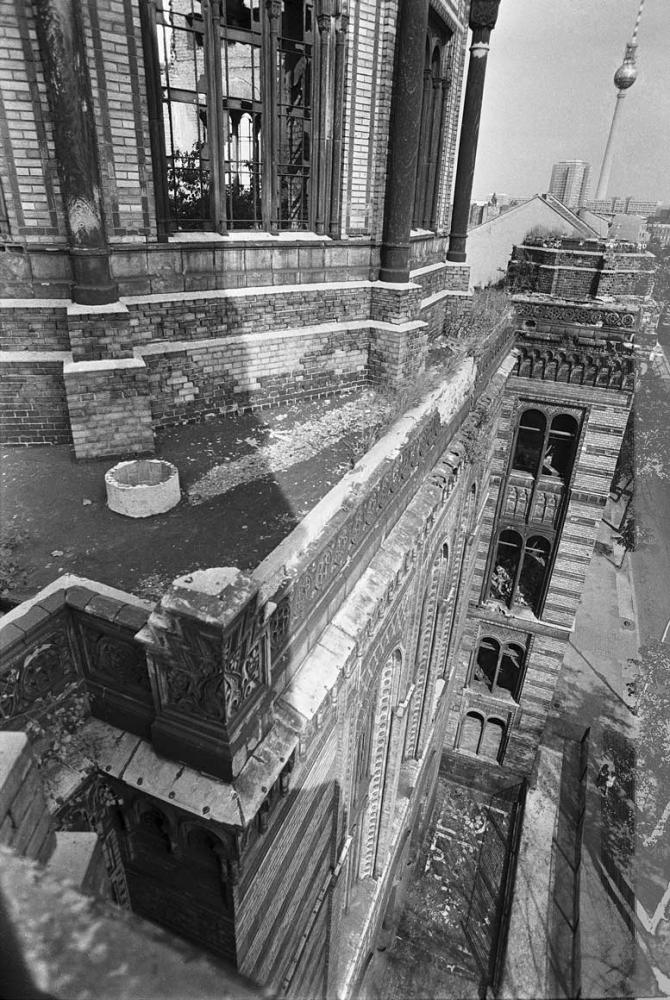

Photo series of the New Synagogue on Oranienburger Straße, photographer: Mathias Brauner, Berlin, September 1987; Jewish Museum Berlin

But beyond the narrow confines of the state’s remembrance policy and long before the policy shifts of the 1980s, the history of the Holocaust in the GDR could be accessed through many other channels, including novels, autobiographical accounts, plays, and films. The Investigation by Peter Weiss is one example, a documentary theatrical collage dealing with the first Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt am Main. On October 19, 1965, the play premiered simultaneously in fifteen cities in East and West Germany. The East Berlin event, which was broadcast on TV shortly afterward, took place in the assembly hall of the East German Volkskammer, and the parts were read by actors, writers, cultural policymakers, and people persecuted by the Nazi-regime.

Jewish Life Beyond the Communities

An essay such as this that discusses Jewish life in the GDR cannot limit itself to members of the Jewish communities, but must also examine the much larger group of Holocaust survivors who descended from Jewish families but distanced themselves from their ancestors’ religion and traditions. Many had joined the labor movement before 1933 and become members of the KPD. They were loyal to the Soviet occupation force and the Communist Party, in whose sphere of influence they hoped for favorable living and working conditions.

They consisted of writers, actors, directors, singers, composers, and visual artists. They assumed management of the newly founded publishing houses, broadcasting companies, and newspapers. They were appointed to university chairs, became factory directors, or performed functions in the party and state apparatus.

During the Stalinist purges, many faced accusations, suspicions, or – at the very least – professional discrimination. And perhaps it was precisely the persecution they suffered during the Nazi period and their grief over murdered relatives that unconsciously bound them to the socialist project. With their creativity, professional skills, and cosmopolitanism, these women and men made an important contribution to rebuilding cultural life and new political structures in East Germany. Among the best-known are Anna Seghers, Lea Grundig, Arnold Zweig, Alfred Kantorowicz, Stefan Hermlin, Ernst-Herrmann Meyer, Alexander Abusch, Albert Norden, and Hanns and Gerhart Eisler.

One exceptional figure among them was Jürgen Kuczynski, a party loyalist and scholar who never gave up his intellectual independence. In 1936, after three years of working illegally for the KPD in Germany, he emigrated to Great Britain, only to return to Berlin in 1945 in the uniform of a US Army colonel. A few years later, he co-founded the Academy of Sciences. Kuczynski also directed the Institute for Economic History, where research was conducted in relative freedom by GDR standards. An internationally respected scholar, he served as advisor to Erich Honecker and often stood out with his undogmatic ideas and unusual initiatives in the closely managed East German public sphere.

Another exceptional figure was the singer and dancer Lin Jaldati, who grew up in a poor Jewish family in Amsterdam and joined the Communist Party of the Netherlands in 1936. After the Wehrmacht invaded the country, she joined the resistance against the occupiers. She was arrested and deported to Auschwitz in 1944 and liberated from Bergen-Belsen in 1945. In 1952, she moved to the GDR with her husband, the pianist and former German émigré Eberhard Rebling. She was the only artist to have success as a singer of Yiddish songs well into the 1980s.

Positions on Israel

The SED leadership saw members of the Jewish communities as the only true Jews in the country. However, on certain occasions they exploited the Jewish origins of the many “others” for their propaganda. This occurred in 1961, when the journalists Max Kahane, Gerhard Leo, and Kurt Goldstein – all of whom came from Jewish families – were sent to Jerusalem as special correspondents for the Eichmann trial and instructed to highlight the Nazi past of Hans Globke, a state secretary in Bonn. In addition, in June 1967, one day after the start of the Six-Day War between Israel and its Arab neighbors, the SED Politburo decided to publish “statements by Jewish citizens of the GDR expressing outrage at Israeli aggression and the Israel-Washington-Bonn conspiracy.”

3

Its key motivation was probably to head off accusations of antisemitism. Albert Norden had been charged with the task, but as he noted confusedly (or indignantly?) to Walter Ulbricht, many of the Jews he approached refused to participate. In the end, none of the signers of the declaration published in Neues Deutschland on 9 June 1967, were members of a Jewish community. However, Jewish community functionaries, particularly in the 1980s, became increasingly confident about criticizing antisemitic lapses in East German coverage of the Middle East conflict and Israel.

As a result of the GDR’s hostile policy toward Israel, the Jewish communities were largely barred from contact with international Jewish organizations. It was not until 1986 that delegates from the umbrella association were permitted to attend a meeting of the World Jewish Congress in Jerusalem. Earlier, after years of isolation, the Jewish communities had begun to send out feelers to the “external world within” – that is, to East German society. In the 1980s, they regularly held concerts, readings, and lectures in Berlin and Leipzig. Around the same time, working groups were founded in several large cities to promote Christian-Jewish dialogue.

New Members for the Communities?

In the 1980s, the Jewish communities in East Germany had a total of around four hundred members. Roughly two hundred belonged to the community in East Berlin. In 1986, the executive board in Berlin, under the leadership of Dr. Peter Kirchner, took an unusual step to stop the decline and aging of the community. It invited many of the adult children of secular Jewish communist families to a community event. The response was overwhelming. The initiative met with growing interest among a younger generation that wanted to learn more about their roots and rediscover the values, traditions, and practices their parents or grandparents had given up so long ago. They formed the group “Wir für uns” (We for Ourselves) and took part in services, festivals, and Hebrew lessons – though few ultimately joined the Jewish community. Most preferred loose ties, discussions, lectures, and cultural events – in other words, membership in what was essentially a Jewish cultural association. This type of association was not founded until 1990, by which time the GDR’s existence had almost come to an end.

Annette Leo, historian and publicist

This text is a significantly abridged version of her contribution to the exhibition catalog Another Country Jewish in the GDR.

Menorah, Manufacturer: VEB, Wohnraumleuchten Berlin, Berlin, ca. 1975–1989; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of the Berlin Jewish Cultural Association, photo: Roman März.

- Deutsche Volkszeitung, July 1, 1945, cited in Elke Reuter and Detlef Hansel, Das kurze Leben der VVN von 1947 bis 1953 (Berlin, 1997), 80–81. This is probably a quote from Ottomar Geschke, the first chairman of the main OdF committee in Berlin and later chairman of the VVN. ↩︎

- See Stefan Küchler, “DDR-Geschichtsbilder: Zur Interpretation des Nationalsozialismus im Geschichtsunterricht der DDR,” Internationale Schulbuchforschung 1 (2000), vol. 22, 42–44. ↩︎

- Protokoll Nr. 7/67 der Politbürositzung am 7.6.1967, Anlage 1; SAPMO, DY 30/J IV2/2/1 117, cited in Ulrike Offenberg, “Seid vorsichtig gegen die Machthaber”: Die jüdischen Gemeinden in der SBZ und der DDR 1945 bis 1990 (Berlin, 1998), 201. ↩︎

Citation recommendation:

Annette Leo (2023), Singled Out and Viewed Suspiciously: Jews in the GDR.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/10076

Exhibition Another Country. Jewish in the GDR: Features & Programs

- Exhibition Webpage

- Another Country. Jewish in the GDR: 8 Sep 2023 to 14 Jan 2024

- Publications

- Another Country. Jewish in the GDR: Catalog accompanying the exhibition, English edition, 2023

- Ein anderes Land. Jüdisch in der DDR: Catalog accompanying the exhibition, German edition, 2023

- Digital Content

- Voices from the GDR: Twelve short film interviews with Jewish perspectives on life and the political system, 2023, in German with English subtitles

- Come Fly With Me Over the Brandenburg Gate: A documentary by Esther Zimmering, in German

- Current page: Singled Out and Viewed Suspiciously: Jews in the GDR: Abridged version of Annette Leo’s contribution to the exhibition catalog, 2023

- Jewish in the GDR. A Road Trip with Marion and Lena Brasch: A podcast by Deutschlandfunk Kultur in cooperation with the Jewish Museum Berlin, six episodes, 2023, in German

- Jewish Local History of the GDR: Information about the communities in Dresden, Erfurt, Halle, Leipzig, Magdeburg, Chemnitz and Schwerin on Jewish Places

- City Walk Berlin-East: Tour with Jewish Places from the New Synagogue to the kosher butcher’s shop, school participation project 2022/23

- Soundtrack of the Exhibition: Playlist on Spotify

- See also

- East Germany