“It’s Complicated”

A Text by Simone Bloch, Daughter of Curt Bloch

Like most teenagers, I failed to share my father’s sense of humor. By my standards then, it wasn’t even clear he had one. Around the house we disagreed about almost everything and winning an argument was as close as we came to playing a sport. Now almost fifty years have passed since my father died suddenly when I was fifteen years old. Over time I’ve come to think of him as a generous and funny character who would be astonished at how completely we – he and I –have overcome our differences. I imagine he’d be impressed and overjoyed that I’ve dedicated myself to bringing to light his talent and remarkable body of work, Het Onderwater-Cabaret.

When my father wanted to make some irrefutably wise point to me, he would resort to quoting some long rhyme by Goethe or Heine or Schiller in German. To me it sounded like a magic spell. I had no idea what he was saying because I happened to be a kid he was raising in the 1970s in New York City. In a cartoon, the thought balloon above my head would have read: “If those are real words he’s saying, they rhyme.” The piece of doggerel he often quoted in English was known as “The Optimist’s Creed”, most famously the slogan of Mayflower Donuts, a chain founded by Adolph Levitt, a Jewish-Bulgarian émigré who became known as The Donut King:

As you ramble on through life, brother,

Whatever be your goal

Keep your eye upon the donut

And not upon the hole!

I got that. It boiled down to that one quote of Nietzsche that everyone knows, “What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.” Except it’s about donuts instead of death. And it rhymes. As a little girl, the first big word I learned how to use was “complicated.” It meant “hard to explain” and it seemed to be the answer to most questions related to our family. Being Jewish had nothing to do with what made us different. Our Jewish identity was the one normal thing about us in New York City at a time when there were more Jews there than in Israel.

Our house in Queens appeared identical to the others on the block, but inside our neighbors’ homes were Jewish dads who had served in the US Armed Forces, whose wives were stay-at-home mothers who didn’t know how to drive. Every morning my mother hopped into her Oldsmobile 88 station wagon and drove to work at my parents’ store in Manhattan, Continental Antiques. I stayed home with Ida, the Catholic German nanny who shared my bedroom and let me help her light candles at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on the way to art classes at the Museum of Modern Art. My favorite painting was Henri Rousseau’s Le Rêve, but in order to get there one had to pass Picasso’s Guernica, commemorating the Nazi aerial bombing of a Spanish village during the Spanish Civil War. It haunted the stairs leading to all the exhibits.

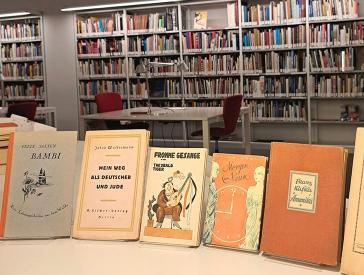

On our block my friends had grandparents and aunts and uncles who came to visit. They went to baseball games at Shea and Yankee Stadium. Their houses were decorated with retouched family photos, wall-to-wall carpeting, and Chagall prints alongside displays of formal dinnerware. Our house was a kind of museum, decorated with Persian rugs and oil paintings and way too many books, about art, literature, history. Some in English, most not. In the basement we had a fullsize French carousel horse, a Polynesian devil’s mask, and a stuffed leopard’s head. We drove into Manhattan to museums and concerts. Of course, I had a Barbie, but my father also started a collection of small animal bronzes for me – birds and bears and kittens. Each time he returned from a buying trip, he’d open his suitcase and hand them over straight away, along with other exotic treasures: perfume, chocolates, dolls, and silk scarves. He brought these gifts back from a world that no longer existed, from which only he could travel back and forth. In New York we lived in a house full of conversation pieces we didn’t talk about. Het Onderwater-Cabaret (OWC) was yet another relic.

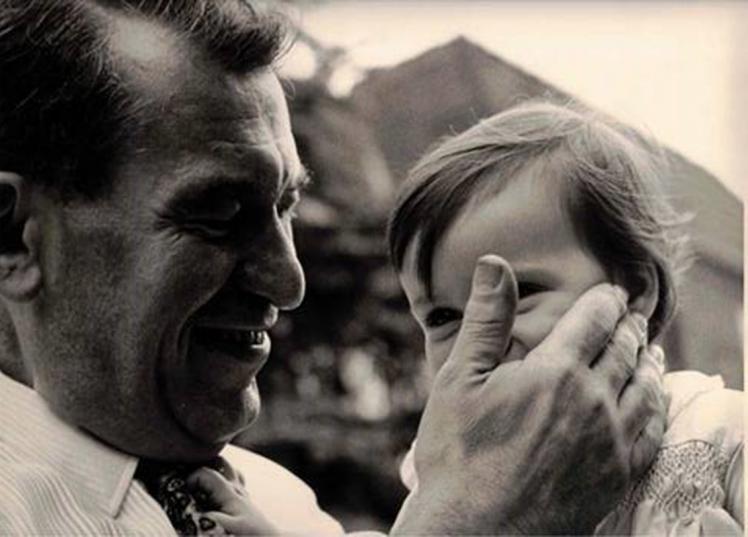

Curt Bloch with his daughter Simone, 1950s; photo: courtesy of Simone Bloch

"What did you think when you came upon this treasure?" I’ve been asked a version of this question many times and can only repeat the same disappointing answer. There was no “moment of discovery.” In Amsterdam after the war, my father had the Onderwater-Cabaret bound into four thick compact volumes to preserve and keep them organized. Anyone who ever met him knew he had a lot to say and he’d decided the OWC belonged on the bookshelf. Our house was filled with lots of weird stuff that had come from Europe in addition to my parents themselves. Were the antiques they sold at Continental Antiques junk or treasures? Either way, they were out of synch with chronological time and space; mute objects carrying stories they would never tell, and definitely not in English. The OWC was no buried treasure, it was always accessible, within reach physically. Its frame of reference could only build with time. I would not question why it was in our dining room any more than I would have wondered why the table came from a French library.

Educated émigrés of my parents’ generation believed that assimilation was possible, desirable, and could be achieved relatively quickly if you “just learn the language.” That proved to be complicated. To my brother and me my parents spoke only English, but to each other they often spoke German. Every bit I understood was a triumph. Understanding Dutch was a hopeless proposition; code for keeping real secrets. In Queens our neighbors spoke English with such thick New York accents it was hard for us to understand, but fun for me to imitate. My friends found my parents’ heavy foreign accents comical and worthy of mimicry, but I could barely hear them. On American television, characters who shared my father’s accent were Nazis, the butt of jokes on Hogan’s Heroes, then a popular series about American GIs in a German prisoner-of-war camp. It had a laugh track and no Jews.

I do remember once, at the close of a dinner party, my father took the Onderwater-Cabaret off the shelf and read aloud in German. It was during the time of the Watergate scandal, and the poem he read was doubtless intended to point out the injustice of Nixon directing incompetent, lying thieves to maintain his power and keep fighting the war in Vietnam. Even after he translated it into English, the parallel was impossible for a room full of monolingual, American-born English speakers to grasp. How lonely a feeling that must have been. The people who could appreciate my father’s wit were scattered around the world or dead. The Germans of his own generation were not his audience.

“I read without an accent” he said, and, indeed, he spoke and read many languages well. In English his jokes didn’t always land. He made my mother laugh as her mind followed his back and forth over the ocean, but my mind didn’t travel that way yet. What did I know of how his history intersected with Europe’s? Not much. His nose had been broken in a street fight with Nazis at a newspaper office in Dortmund. Maybe also his teeth? In the Netherlands my dad had been hidden by a gravedigger with a macabre sense of humor. In the Netherlands my father had come to know hunger for the first time.

I only became curious about my father’s story when he was suddenly gone. I began to study German because it was the only way to ever know where he – where I – came from. Again, this was complicated. While most of the kids I grew up with learned Hebrew and traveled to Israel to make sense of their identity, I gravitated to Germany, the place my father thought of as his homeland. During a semester in the early 1980s at the University of Trier I neither denied nor made much of an issue of my Jewishness or family history. Like me, my German friends had learned about the war at home, but if we talked about it, how could we be friends? We didn’t talk about it. We wanted to be friends.

Shortly before my father’s death in 1975, with both New York City and the market for antiques “in the toilet,” my parents had closed their store. My mother – a young widow out of a job – had a practical desire: to stay busy. She volunteered as a translator for the Holocaust Center in Brooklyn and the Museum of Jewish Heritage downtown, and taught idiomatic English to new immigrants. She learned to play tennis and bridge. “It’s of its time,” she said of the OWC. Who was I to disagree? The cover collages of the magazines were coarse and had nothing to do with the present: Stalin, Hitler, and Mussolini were all long gone. As a rule, we were suspicious of people who were too interested in the war. There was an air of the grotesque about that.

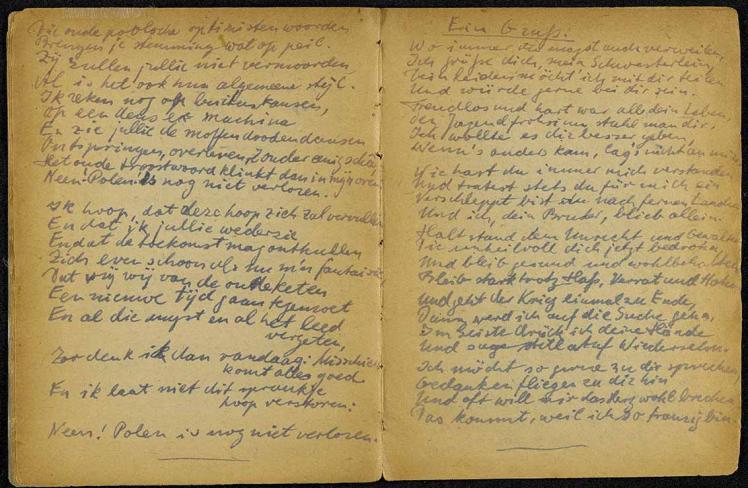

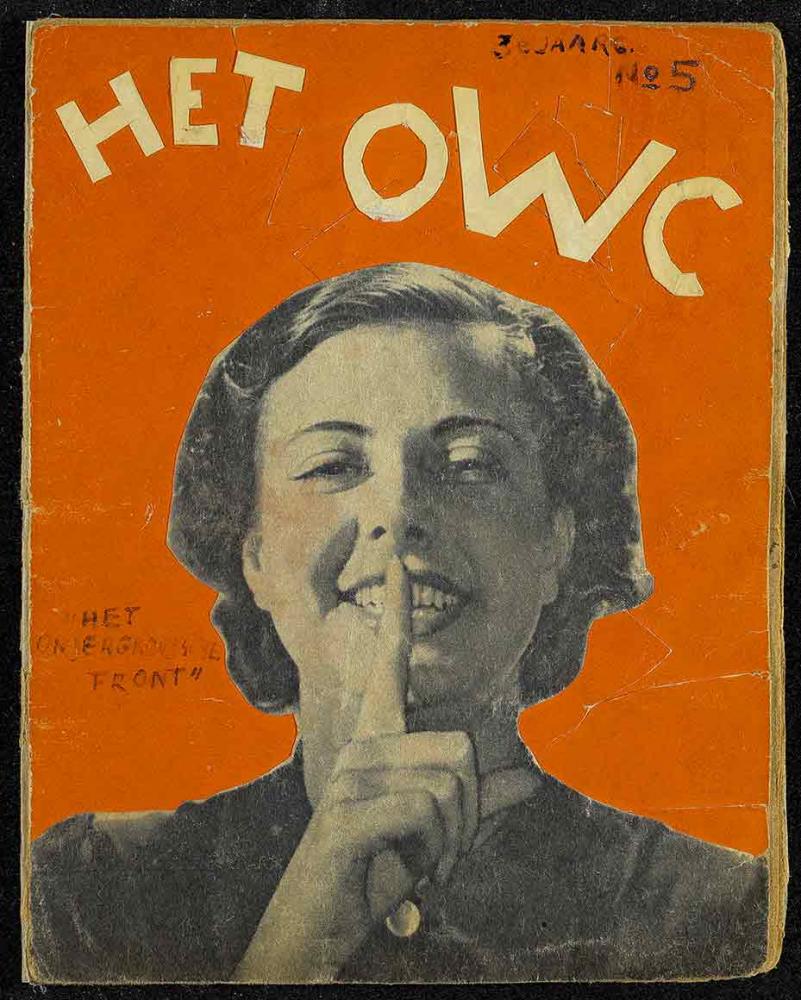

Curt Bloch: "A Greeting", Het Onderwater-Cabaret from August 30, 1943, 2nd edition; Jewish Museum Berlin, Konvolut/816, Curt Bloch Collection, on loan from the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of the Bloch family

When the Berlin Wall fell I learned that German citizenship was my birthright. Along with my two very young daughters, I became a naturalized German citizen. Having children of my own I realized how complicated the many strands of our family history might one day seem to them.

My daughter Lucy was the first to share my father’s poem “Ein Gruß,” and the story behind it, with me. While in college she delved deeper into the volumes of the OWC than I ever had. She studied German in Berlin while trying to learn the answers to questions like: Exactly how unique is the OWC? The answer was “very.” Did any other families have something like this? Unsurprisingly, the answer was no. But how were we to share it? It was old, fragile, and irreplaceable. Unlike the furniture and the curios he brought back to sell at the store, the OWC was my dad’s creation, a product he had made, not something he found at a flea market.

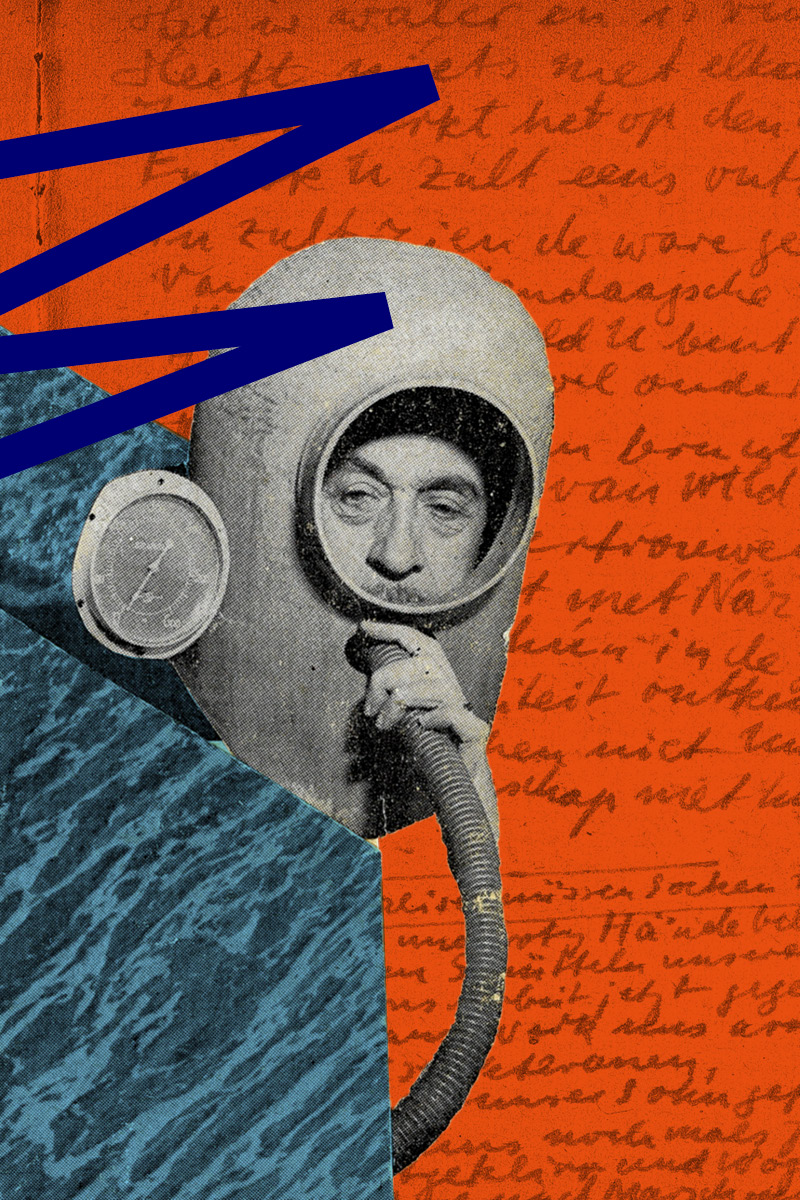

The OWC finally started circulating in 2011 after I brought it to be scanned and digitized at the Leo Baeck Institute in New York. Now I could pose the question of what to do with this unwieldy legacy of resistance. I became a promoter, engaging friends and friends of friends in my struggle to find the right place for my father’s work. I met art historians and curators, psychologists, television producers, archivists, filmmakers, linguists, publishers, grad students, journalists, cartoonists who could all appreciate the uniqueness but found the work uncategorizable. It was then that a first contact to the Jewish Museum Berlin was made. I was convinced my father’s oeuvre deserved to be seen, but I was not ready to donate by that time.

The big upside to Donald Trump is that he’s so easy to make fun of, so when he was elected President in 2016, satire enjoyed a renaissance. It gave me a new way to describe my father: a patriot and originator of subversive free content. Trump was an international target for derision and it became clear that the OWC belonged where its critique of tyranny could be read and understood in the original and applied to the present day.

I’m not shy about talking to strangers. I got that from my father. With help from a journalist neighbor I lobbed the project over the ocean to the Netherlands, where I eventually met Marcel van den Boogert, an editor who introduced Gerard Groeneveld to the material. Meanwhile – on Facebook – I happened upon Thilo von Debschitz, a graphic designer who had brought attention to the work of Fritz Kahn, a brilliant Jewish popular science author. His enthusiasm was unstoppable, and together we brought my father’s story and verse to small audiences at Rotary Club meetings around Germany. Attending via Zoom to answer questions, I could see the surprise and deep emotional effect my father's story and his rhymes had on German speakers. Deliberating on how to bring the OWC to the widest possible audience, we began our work on a dedicated website showcasing my father, his work, and his experience. Thilo encouraged me to re-approach the Jewish Museum Berlin. Hetty Berg, herself from the Netherlands, was utterly enthusiastic and greenlighted OWC’s exhibition premiere.

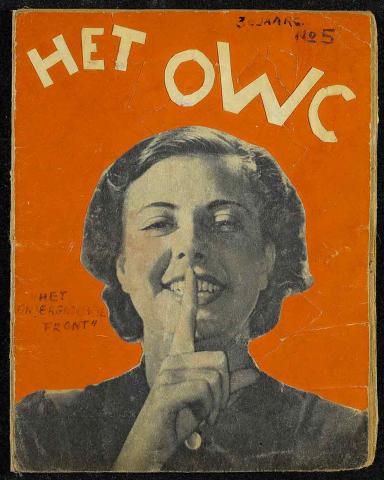

Curt Bloch, Het Onderwater Cabaret, booklet cover from February 3, 1945; Jewish Museum Berlin, Curt Bloch Collection, on loan from the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of the Bloch family

Berlin is where – just shy of one hundred years ago – my father, a nice Jewish boy from Dortmund, lived it up as the world started to fall apart. He arrived here believing the future of Germany might be influenced by someone like him. If only.

Yet somehow, finally that’s true!

It feels magically uncomplicated that the OWC has found its way home to the Jewish Museum Berlin, where beyond this exhibition it will become part of educational and scholarly programs available for intersecting purposes around the world. Together with his online presence, we may have exceeded Curt Bloch’s dream that his Onderwater-Cabaret might receive recognition beyond the walls of his hiding place in Enschede or the bookshelf in our living room in New York.

One of my father’s favorite quotes in English didn’t rhyme and came from Mark Twain:

“When I was a boy of fourteen, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be twenty-one, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.”

Give or take a bunch of decades, that is the story of Curt Bloch (and me), and he would be so delighted to know how wise I believe he has become.

Simone Bloch is a writer, psychoanalyst, mother, and grandmother. She lives upstairs from her own ninetyeight-year-old mother in New York City, a mile as the crow flies from the hospital where she was born. She has held dual US/German citizenship since 1990.

This article was first published in 2024 in issue 26 of the print edition of the JMB Journal.

Citation recommendation:

Simone Bloch (2024), “It’s Complicated”. A Text by Simone Bloch, Daughter of Curt Bloch.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/10286

Exhibition “My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret: Features & Programs

- Exhibition Webpage

- “My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret: 9 Feb to 23 Jun 2024

- Accompanying Events

- Tour of the Exhibition “My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret: Dates by arrangement (from 9 Feb to 26 May 2024)

- Exhibition Opening: 8 Feb 2024

- Curator Tour for FRIENDS OF THE JMB: 8 Apr 2024, in German

- Joodse Vluchtelingen: The Fate of German-Jewish Émigrés in the Netherlands: 3 Mar 2024, in German

- Archival Objects of German Jews in the Netherlands: Show & tell for FRIENDS OF THE JMB, 7 Mar 2024, in German

- Het Onderwater Cabaret Live. An evening of music and poetry: 11 Apr 2024, in German

- Hidden in Enschede: Conversation with Contemporary Witness Herbert Zwartz: 16 Apr 2024, in German

- Publications

- JMB Journal 26: Het Onderwater Cabaret: Special edition on the occasion of the exhibition

- Digital Content

- OWC Online Feature: A Glimpse Behind the Scenes of the Exhibition

- Life and Work of Curt Bloch: Essay with biographical insights, JMB Journal 26

- On the Piano of My Fantasy – Video with Marina Frenk, Richard Gonlag, and Mathias Schäfer, in German, Dutch and German Sign Language

- Current page: “It’s Complicated”: A text by Simone Bloch, daughter of Curt Bloch

- “Ik neurie mee ’t propellerlied…”: Essay on Het Onderwater-Cabaret: A Testament to Political Resistance in the Occupied Netherlands, 1943–45

- Clandestine Literature in the Netherlands 1940–1945: Essay, JMB Journal 26

- All Audio Pieces of the Exhibition with Transcriptions and Translations

- All issues of Het Onderwarter-Cabaret: All 95 issues to browse

- See also

- Survivors in Hiding (National Socialism)

- To the Web Project www.curt-bloch.com