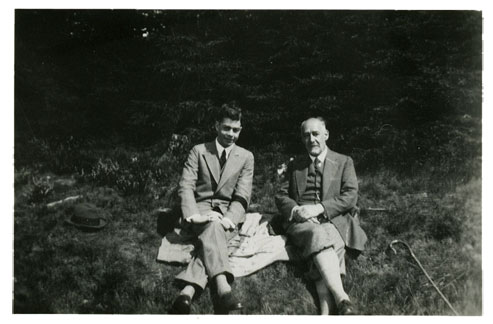

When Bertha Lindenberg was buried in Oderberg on 11 October 1933, rabbi candidate Rudolf Seligsohn (1909–1943)—only twenty-three at the time—held a remarkable eulogy. For Seligsohn, saying goodbye to Miss Lindenberg, a woman with deep roots in the little Brandenburg town, was "a symbol of another, greater farewell." It was a farewell to the Jewish communities in the countryside and small towns, which "will not be able to take up the harsh struggle for existence that the German Jews must now pursue."

The decline of such communities had begun in the mid-nineteenth century as a result of emerging urbanization, the allure of the big cities, and the advance of modernization. Rudolf Seligsohn believed it meant the loss of treasured values, of manual labor, and of a strong sense of connection with the soil. For him, this parting marked the end of endeavors to "lay the foundations of German Jewry afresh" by sustaining smaller communities. It also signaled the failure of hopes to achieve "a healthy and equitable distribution of the adherents of Judaism across our fatherland" by means of new settlements.

Seligsohn could not have guessed what the future would bring—"only a prophet could tell whether German Jews will enjoy the shining light of freedom again"—but he emphasized that "if the gates do reopen," the German Jewish community would have to renew itself. It would have to give precedence not to the path of nineteenth-century emancipation, the path "toward pure intellect, the path into the city," but instead to rootedness in the countryside. He saw the deceased woman and her family as "representatives of true Jewishness," of a Jewishness that "clings to its soil, straight from the root, robust and strong, constructing, preserving, and sustaining."

The funeral of Bertha Lindenberg, who "took her leave at a moment of historical transition," was the last to be held at Oderberg‘s Jewish cemetery, in use since at least 1750. The cemetery was desecrated during the Nazi period and many of its gravestones were lost, while others were simply thrown haphazardly into a heap. After the war the cemetery was cleaned up, and around forty monuments and fragments were reerected. They included Bertha Lindenberg‘s tombstone.

Aubrey Pomerance

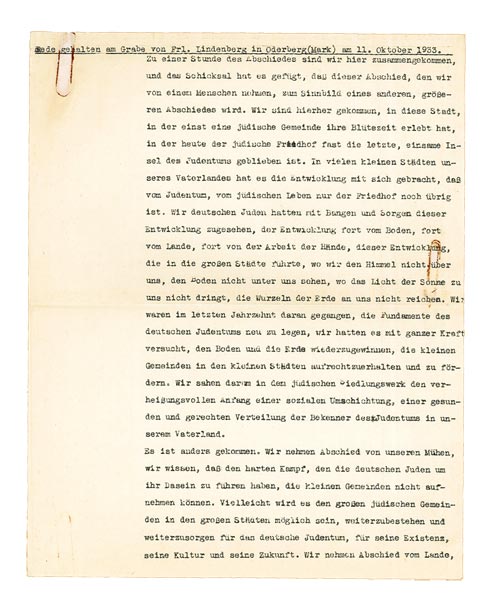

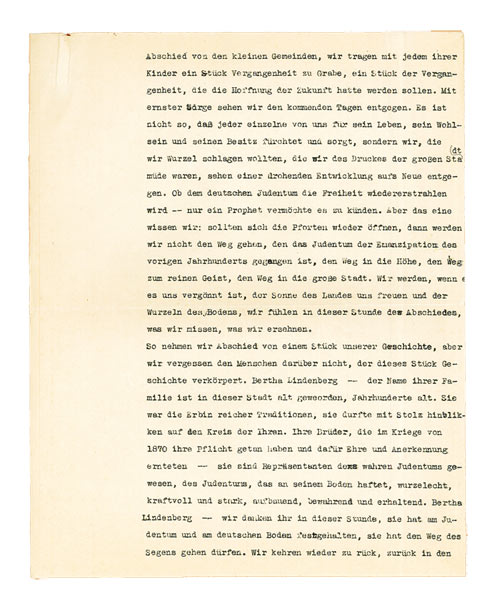

Eulogy at the graveside of Fräulein Lindenberg in Oderberg (Mark) on 11 October 1933

We have come together today at an hour of farewell, and Providence has decreed that this farewell from one human being becomes a symbol of another, greater farewell. We have come here to a town where a Jewish community once blossomed and where today the Jewish cemetery is almost the last, lonely island of Jewry. Developments in many small towns of our fatherland have meant that only the cemetery is left of Jewry, of Jewish life. We German Jews have observed these developments with concern and trepidation: the move away from the soil, away from the countryside, away from manual labor; the move that has led us into the big cities where we cannot see the sky above us or the earth below, where the light of the sun does not touch us, the roots of the soil do not reach us. In the past ten years, we have begun to try to lay the foundations of German Jewry afresh; we have tried with all our strength to win back the land and the soil, to sustain and nurture the small communities in little towns. In the Jewish settlement movement, we saw the promising beginnings of a social reconfiguration, a healthy and equitable distribution of the adherents of Judaism across our fatherland.

But it was not to be. We say farewell to those efforts, knowing that the smaller communities will not be able to take up the harsh struggle for existence that the German Jews must now pursue. Perhaps it will be possible for the large Jewish communities in bigger cities to continue to exist and continue to care for German Jewry, for its existence, its culture, and its future. We say farewell to the countryside,

(page 2)

farewell to these small communities. With each of their children, we bear a piece of the past to its grave, a piece of the past that we thought would become a hope for the future. We look to the coming days with great apprehension. It is not that each of us fears and worries individually for his own life, his well-being, and his property; but we who wanted to put down roots, we who were weary of the pressures of the big city, once again find ourselves facing a perilous tendency. Only a prophet could tell whether German Jews will enjoy the shining light of freedom again. But one thing we know: if the gates do reopen, then we will not follow the path chosen by Jews during the emancipation of the last century, the path upward, the path toward pure intellect, the path into the city. We will, if it is granted to us, delight in the sunshine of the countryside and the roots of the soil; in this hour of parting we sense what we lack, what we yearn for.

Yet in saying farewell to a part of our history, we do not forget the human being who embodied that part of history. Bertha Lindenberg—the name of her family has grown old, centuries old, in this town. She was the heir to rich traditions, she could look with pride at the circle of her kin. Her brothers did their duty in the war of 1870 and earned honor and respect for it—they were representatives of true Jewishness, of the Jewishness that clings to its soil, straight from the root, robust and strong, constructing, preserving, and sustaining. Bertha Lindenberg—we thank her at this hour, for she held fast to Jewishness and to the German soil, she was permitted to walk the path of blessedness. We will return, go back to

(page 3)

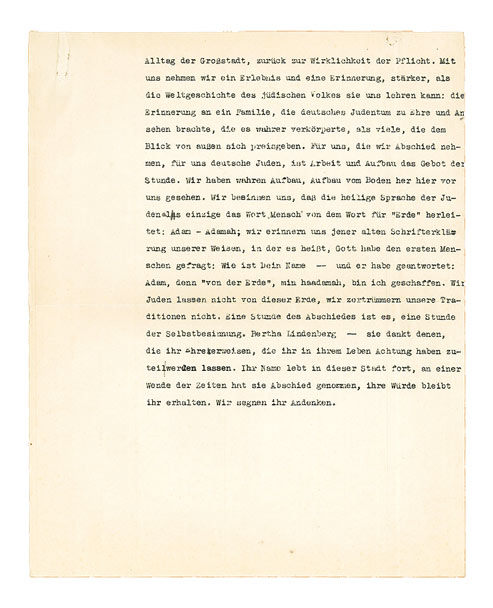

the everyday life of the metropolis, back to the reality of duty. We will take with us an experience and a memory stronger than any that can be taught by the world history of the Jewish people: the memory of a family that brought honor and esteem to German Jewry, that embodied it more truly than many who offer themselves to the gaze of outsiders. For us who are saying farewell, for us German Jews, the time has come for working and for building. We have seen true building, building up from the soil, here before us. We recollect that the sacred language of the Jews is the only one in which the word for "man" is derived from the word for "earth": Adam—Adamah; we remember the ancient exegesis of our sages, which tells us that God asked the first man: What is your name? And that he answered: Adam, for I was created from the "dust of the earth," min haadamah. We Jews will not abandon this earth, we will not demolish our traditions. This is an hour of parting, an hour to take stock of ourselves. Bertha Lindenberg—she thanks those who show her honor, those who gave her respect during her life. Her name lives on in this town. She took her leave at a moment of historical transition; her dignity survives. We bless her memory.