“Weapons and Dignity” is the title of the chronicle of an object in the recently published 25th anniversary brochure of the German Historical Museum. It is about a revolver that was offered as a donation to the Jewish Museum, met with great interest there, but finally found its way into the collection of the German Historical Museum. Why?

“Weapons and Dignity” is the title of the chronicle of an object in the recently published 25th anniversary brochure of the German Historical Museum. It is about a revolver that was offered as a donation to the Jewish Museum, met with great interest there, but finally found its way into the collection of the German Historical Museum. Why?

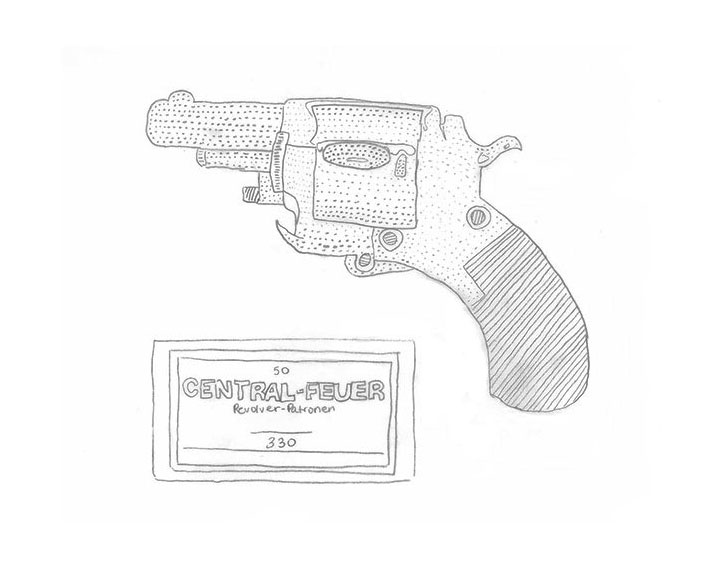

The story: a woman in Berlin during the National Socialist era, fearing for her life because she was ‘half-Jewish,’ obtained a revolver so that, should she be threatened with deportation, she could end her life instead. She survived the era of persecution and kept the revolver as a souvenir, eventually giving it to a neighbor. He in turn made contact with the Museum when he was to be required by changes in the law regulating weapons possession to register the weapon or surrender it to authorities. For an institution like the Jewish Museum Berlin, where biographical narratives play an important role in the collections and in the permanent exhibition, this revolver would have been a very welcome ‘strong’ object, given the immediacy of its provenance.

However: a telephone call with the curatorial colleague at the German Historical Museum responsible for 30,000 military objects revealed that it wouldn’t be so easy to adopt this exhibit. Firearms have a peculiar status, even in a museum: the curator responsible for them must have a license. Ergo… I myself would be required to apply for a firearms license – what an outlandish notion! I had actually only wanted to get an expert opinion on dating the revolver in order to verify the conclusiveness of the oral record on the object. Now the affair was taking an unexpected turn.

A second phone call, this time with the relevant officer at the police headquarters at Platz der Luftbrücke, informed me that I need to acquire the certificate – the “gun license” – officially. Firearms training, a state examination, and only then could I even think about picking up the revolver with my own hands.

Perhaps it would be preferable after all to pursue the alternative: having a gunsmith disarm the weapon? Of gunsmiths, however, there are a very few left –none at all in Berlin. And aside from this, such an infringement on the object’s historicity would devalue it.

We ultimately had to reject both possibilities, since a single firearm in the Jewish Museum’s collection wouldn’t justify the effort to secure a weapons permit. What could we do, then, to prevent all the history belonging to this object from being lost?

Now I made a third call: would the curator colleague at the German Historical Museum be interested in making this weapon part of their collection? If so, I could put him in contact with its present owner. The answer was “yes”: the museum’s collection did not yet have this model of revolver. And the biographical factor that usually plays a marginal role in the collecting perspective of the militaria department there, which is otherwise devoted to military history, made this object particularly interesting and singular for the museum. So in the interests of all concerned parties, the revolver survived intact, and its history can now be told to a broader audience.

Leonore Maier, Collections