With her works for our art vending machines, Deborah Wargon exposes things that got swept under the rug

A cordial welcome, the wafting flavors of a freshly-cooked meal, a light-drenched room with a high ceiling, full of brightly-colored books and pictures, and a piano with a sign-post ‘to Australia’ sitting on it… My first encounter with Deborah Wargon in her live-in atelier in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood is a far cry from the rather severe, somber associations that the term ‘testament enforcer’ brings up for me. Wargon – a musician as well as visual and theater artist born in Melbourne in 1962 – describes herself this way on the package insert that comes with the small-scale artworks that she created for the art vending machine in our permanent exhibition. Those artworks bear the title “The Legacy of Friede Traurig” – where Friede Traurig doubles as a proper name and, in German, to mean peace sorrowful. And Deborah Wargon, who is best known for her paper cuttings inside former insect cases, says that she would rather be sorrowful.

With a little good luck, you may get one of her works from the vending machine: for instance, a little human figurine made of rail track ballast (gravel), wire, and newspaper. Aside from the expressive name Friede Traurig, the materials invoke woeful stories of train transports and barbed wire fences, particularly because the newspapers she used are from the Second World War. But for the artist, it’s clearly not only about the specific time the Nazis were in power and the Shoah. It’s also about the legacies, the inheritance, the stories that we all carry with us. She explains her choice of materials: “For me, wire is a fascinating material. It’s also used for cages. So you can use to suggest the ways that we’re all captive.” The rail track gravel, which normally lies on the ground, relates for Wargon to the ground that we all walk on, as descendants of the people who came before us. “Besides, in both German and English there’s the expression ‘to sweep something under the rug’”. The gravel, or grit, that we bring into the house on the soles of our shoes, and then sweep under the rug, stands for something that we don’t want to face and deal with.

The gravel stone that’s incorporated into the figurines thus also represents the burden of legacies. The individually-made pieces each show that this burden can appear all over, in a person’s head, their heart, stomach or belly. Each figurine is provided with the cheerful tongue-in-cheek suggestion “It’s never too late to have a happy childhood.”

I was convinced immediately that the artist, who gives an infectious fun-loving impression, does hope to build something unique and life-affirming on these bewildering layers of history and legacy.

To accompany the pieces in the art vending machine, Wargon wrote a fairy tale – that also ends by awakening hope and is teeming with ideas from the discourse on memory. Her great-great-grandmother was in fact named Friede Traurig. In the same way that the name sounds like an allegory, she uses the form of a fairy tale to validate the artwork beyond her own biography, unlocking her interpretations of the art for others. For example, from my own reading of it, I could see in the motif of giving birth as a metaphor, among other things, for the creative process of an artist:

“A long, long time ago, time came to the womb and spoke to it, saying that now was the right time to give birth. And so it happened that the water broke and the womb brought legacy into the world.”

It was in face like this for her, answered the artist to this inquiry: she always finds herself ‘pregnant’ with ideas for artworks before she brings them into the world. All told, she is surprised when some people here in Germany tell her that her art is so ‘feminine’. After all she works with human bodies in her paper cutting – masculine as well as feminine forms.

I glanced at a paper cutting on the wall, a picture of two babies still connected to their mother by their umbilical cords. Wargon tells me that her artistic preoccupation with motherhood also has something to do with her Jewish identity, which she’s grappled with intensively in the last few years. Motherhood (especially of children who didn’t come) was already an important issue for biblical matriarchs like Sara and Rebecca.

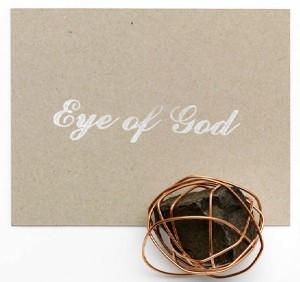

Wargon’s second piece for the art vending machine also emerges from her addressing her Jewish identity. This one has the title “Eye of God” and it’s a piece of rail track ballast wrapped in a thicker and shinier wire, that sort of brings to mind a model of an atom. “I wasn’t raised religious and I don’t believe in God. When I read the ten commandments, they seem rather vain and patriarchal – and have something of Big Brother about them. So God also belongs to the gravel-ground on which I’ve built my identity as a modern Jew – only, like the singular self-contained atom, he stays inaccessible to me.”

Mirjam Bitter, Media

Enigmatic. Images of wire and paper come to mind in unexpected ways. The first with many uses – to bind, to hold together, to carry electricity – as well as to segregate and separate. To join together and pliable when warm. Harsh, sharp and threatening when used as razor wire. Paper too has many uses. Almost ephemeral when used to embody the emotions of a love letter upon it – yet just as plausibly used to enforce a death sentence with the stroke of a pen to witness the will of a tyrant.

Debbie’s work is enigmatic. She could be revealing any of these things. Or none of them. Something else perhaps. Spellbound in the mystery of conjecture, the viewer is held in thrall.