On our “Open Day at the Academy,” this Sunday, 27 October 2013, we will celebrate the namesakes of the new public square in front of the Academy on Lindenstrasse: Fromet Mendelssohn, née Gugenheim, and her husband Moses Mendelssohn are now immortalized on Berlin’s cityscape, following much debate and deliberation. Reason enough to find out more about this exceptional couple!

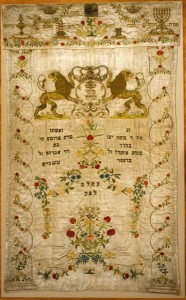

Inspired by deep religious feeling, Fromet and Moses Mendelssohn had Fromet’s wedding dress converted into a Torah curtain. They presented it to Berlin’s Jewish community, where, in the synagogue, it decorated the shrine.

You can find this and other objects relating to Moses Mendelssohn held by the Jewish Museum Berlin in our collections …

In the spring of 1761, when philosopher Moses Mendelssohn met the merchant’s daughter Fromet Gugenheim during a visit to Hamburg, his fate was sealed: he declared his love for her in a garden pavilion, and “stole a few kisses from her lips.” He returned, besotted, to Berlin and wrote to his friend Gotthold Ephraim Lessing:

“I have committed the folly of falling in love in my thirtieth year. The woman I wish to marry has no assets, is neither beautiful nor erudite; yet I am a lovesick beau, so smitten that I believe I could live with her happily ever after.”

The two were wed in June 1762. That they married for love was highly unusual: most marriages at the time were arranged by matchmakers. “[O]ur correspondence can do without ceremony,” Moses assured Fromet on 15 May 1761, in the very first of his letters to his bride: “…our hearts will respond.”

“Before I met you, my love, solitude was my Garden of Eden. But it is intolerable to me now.” Berlin, 24 October 1761 → continue reading

Area on the Majdanek Trial in the permanent exhibition

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Alexander Zuckrow

Forty-four portraits have been mounted in the permanent exhibition over the last few weeks. They are a series of paintings by Minka Hauschild, called “Majdanek Trial Portraits,” and they show the participants of the Majdanek Trial, that took place at the regional court in Dusseldorf from 26 November 1975 until 30 June 1981. Standing in front of the wall of portraits, viewers are left to wonder: “Who is who, here?” The paintings themselves don’t reveal whether the subject was a former prisoner or an SS officer. Some portraits are realistic, but others seem distorted or blurred to the point of being unrecognizable. All of the people portrayed appear to have been damaged in some way. The portraits are deeply disturbing.

Our visitors can find out on iPads lying on the benches nearby whether a given painting depicts a judge, a lawyer for the defense, a witness, or a defendant. Each individual’s role in the Majdanek trial is described here and insight is provided into their biography as well as – where the sources permit – their own perception of the proceedings. → continue reading

A New Space for the Auschwitz Trial in the Permanent Exhibition

Last October I wrote a blog post about Memorandum, a Canadian documentary film about the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt (1963 – 1965). An excerpt of this film has been part of our permanent exhibition for a number of years already. We observed that the film clip elicited a much more intense response from visitors to the legal proceedings of Nazi criminals in Frankfurt than did other forms of media, such as photographs or audio clips. For this reason, documentary film material has been made the central focus of the newly designed area of our permanent exhibition.

“My husband was very accurate, indeed, but […] I can’t imagine all this,” said the wife of Auschwitz perpetrator Wilhelm Boger to NDR journalists

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Alexander Zuckrow

Just a few days ago we re-opened this space with the title “On trial: Auschwitz/Majdanek.” In order to convey how the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt shaped and changed public attitudes towards the past in Germany, we now show a variety of excerpts from contemporary television coverage. In the international coverage of the trial, groundbreaking questions were raised about the way the National Socialist era was officially and publicly dealt with. → continue reading