Film Historian Claudia Dillmann on the Artur Brauner Film Collection in Our Library

The German film producer and Shoah survivor Artur Brauner has kindly donated to our Museum twenty-one films on the subject of the Shoah and the Nazi era—you’ll find the complete list on our website. Today, the Museum acknowledges our great appreciation of this gift with a special event in the presence of Artur Brauner and his family.

Claudia Dillmann

Photo: Deutsches Filminstitut/Uwe Dettmar

Prior to the event we interviewed film historian Claudia Dillmann about Artur Brauner and the appeal of his film productions, in particular for a Jewish Museum. Ms. Dillmann is Director of the German Film Institute in Frankfurt Main and a renowned expert on Artur Brauner, and also initiated the online resource www.filmportal.de. She talked to us about Brauner’s interest in the victims of Nazi crimes, the balancing acts it has called for, his veneration of Romy Schneider, and the German public’s tastes.

Mirjam Bitter, Blog Editor: Ms. Dillman, in your opinion, how representative is our Artur Brauner Film Collection of Mr. Brauner’s entire production list?

Claudia Dillmann: The films that Artur Brauner has donated to the Jewish Museum are indeed representative since they constitute a pivot of his career—one very dear to his heart—namely an abiding commitment to exposing the Holocaust, not least because forty-nine of his own relatives also lost their lives then. He sees these films as his personal “legacy,” one he has been forging since the start of his career. They are dedicated to victims of the Nazi regime and constitute a cycle that in his view is still not complete. In them, he has continually explored new facets of persecution under the Nazi terror and of the traumata he lived through himself. → continue reading

The “Daughters and Sons of Gastarbeiters” (guest workers) are the Academy of the Jewish Museum Berlin’s guest on 14 October 2015, part of the “New German Stories” series. As children, these Berlin authors followed their parents to Germany from their home villages in Anatolia, southern Europe and the Balkans, or they were born into working-class neighborhoods around Germany. Their mothers and fathers were supposed to bolster the German economic recovery as mere “guest workers”. The authors tell their personal stories, look back, follow their parents’ paths and thus add to Germany’s culture of memory. In advance of the event, we’ve asked three questions of Çiçek Bacık, the project’s leader and co-initiator:

Çiçek Bacık © Neda Navaee

Ms. Bacık, how did the “Daughters and Sons of Gastarbeiters” come to be and what was the motivation to tell these personal stories?

Last year, I went to a reading with my friend, the journalist Ferda Ataman. We were sitting in a bar afterwards. “Ferda, we have to start telling our stories and share them with others. We ourselves have to shed light on a dark chapter of our past we’ve successfully repressed,” I said. “Sure, and what’s stopping us?” That was the starting point for “Daughters and Sons of Gastarbeiters”. Our first reading took place in January 2015 at the Wasserturm in Kreuzberg. → continue reading

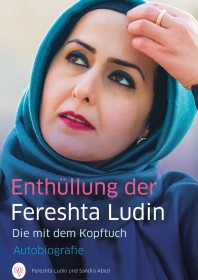

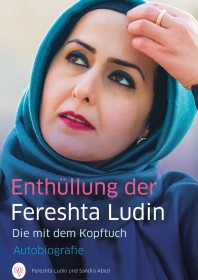

A Conversation with Fereshta Ludin about the Headscarf Debate, Discrimination, and Her Hopes for the Future.

To win the right to work as a teacher in the classroom while wearing her headscarf, Fereshta Ludin had to go all the way to the German Supreme Court (see below). On 17 September 2015, she will join us as part of the series “New German Stories” to introduce her book Enthüllung der Fereshta Ludin. Die mit dem Kopftuch (“The Unveiling of Fereshta Ludin: The One with the Headscarf”). Rafiqa Younes and Julia Jürgens spoke with her in the lead-up to the event.

Book cover © Deutscher Levante Verlag

Ms. Ludin, did you ever guess that the first lawsuit you filed against your employers, in 1998 when you were 25 years old, would set off a nationwide debate about the headscarf ban?

You can’t really imagine something like that. I was still very young and idealistic. I wanted to work as a teacher and had no intention of provoking the public or any politicians.

From your perspective, was it worth it to go all that way through courts, becoming, as you did, a public figure – “the one with the headscarf” as the title of your book ironically references?

I don’t regret a single step along the way. I would have regretted much more, to have had to endure the injustice. I took an active stand against discrimination by going through the courts. Many other women were also affected. It was never my aim to become a public person. → continue reading