A Birthday Tribute to an Inquisitive Storyteller

Book cover of the German edition of “Jews and Words”

© Jüdischer Verlag im Suhrkamp Verlag

On the occasion of his 75th birthday on 4 May, we wish to congratulate Amos Oz, a great writer who visited the Jewish Museum Berlin no less than twice last year. The award-winning Israeli author—he has received, inter alia, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (1992) and, more recently, the Franz Kafka Prize for Literature (2013)—and his daughter, the historian Fania Oz-Salzberger, presented their jointly written book Jews and Words (2012) here last October. In four highly entertaining chapters, “secular Jewish Israelis” draw on the genealogy of reading and writing to trace historical continuity in Jewish traditions. They ask which female poet may have penned the Song of Solomon, reflect on other “vocal women,” and philosophize on matters such as the importance of time and the interplay of collectivism and individuality.

Building in a real kibbutz, photo: Mirjam Bitter

In March 2013, Amos Oz paid a visit to the Museum wearing his literary author’s hat, so to speak, to present his latest publication Between Friends (2013, Hebr. original Be’in Khaverim 2012). The eight interconnected short stories in the volume are set in the fictitious Kibbutz Yekhat and immediately attest the author’s familiarity with kibbutz life. Oz left his intellectual father’s home for a kibbutz at the age of fourteen and a half, and lived and worked there for three decades. His descriptions of typical kibbutz settings—the communal laundry, kitchen, and dining room, the cowsheds and chicken coops, huge orchards and swimming pool—instantly made me feel at home, too, since I lived for a while on a kibbutz in the late 1990s. Discussions at Yekhat about the children’s house, on the other hand, situate the action specifically in the 1950s, the Golden Age of kibbutzim.

The stories deal with the universal constants of human nature: love, loneliness, and the struggle to make major decisions in life. → continue reading

The Festival of Liberation at the Front

Yesterday evening, Monday, 14 April 2014, was the start of the eight-day Passover festivities. These kick off each year with the first Seder, the name of which derives from the Hebrew word seder, meaning order, because a particular ritual sequence is observed the entire evening.

The ritual Seder program is laid down in the Haggadah, an often beautifully illustrated book. (Incidentally, some especially precious Haggadot are currently on display in our special exhibition “The Creation of the World” and our director of archives recently described in his blog why even a nondescript Haggadah might be of great value to a museum.) Traditional texts and songs are recited from the Haggadah. Symbolic dishes and drinks deck the tables, ready to be consumed at specific moments during the evening.

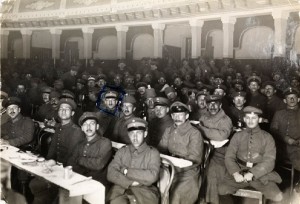

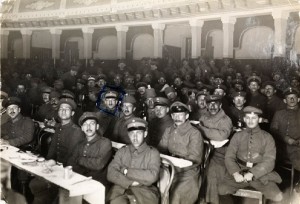

German soldiers celebrate Passover in the occupied town of Jelgava (near Riga). © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: anonymous. Donated by Lore Emanuel

But why is this night different from all other nights? This is a question that Jews all over the world ask themselves year after year at the Seder dinner. The answer is: it is the festival of liberation, for it commemorates the Israelites’ exodus from slavery in ancient Egypt. Everyone is supposed to feel, each year, as if she or he personally is about to leave Egypt. As a token of tribute to this new-won freedom, people comfortably recline while eating and drinking—for to take this position was the prerogative solely of free individuals in antiquity, not of slaves. → continue reading

A Newly Acquired Passover Haggadah and Its Previous Owners in Kreuzberg

Next week, the first Passover Seder will be celebrated on the evening of April 14. All over the world Jews will gather with their family and friends around festively decked tables and partake in the centuries-old tradition of reciting the Haggadah. Its text describes the story of the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Ancient Egypt and sets forth the order of the evening.

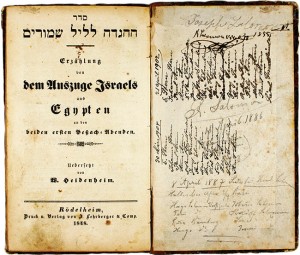

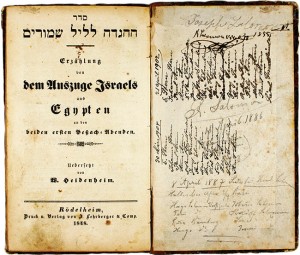

“An Account of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt on the First Two Evenings of Passover,” published in Rödelheim near Frankfurt, 1848

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Aubrey Pomerance

A Haggadah in an online auction recently caught my eye, and I managed to purchase it for a negligible sum for the Jewish Museum Berlin. Published in 1848 in Roedelheim near Frankfurt under the title Erzählung von dem Auszuge Israels aus Egypten an den beiden ersten Pesach-Abenden (An Account of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt on the First Two Evenings of Passover), the book contains the Hebrew version of the Haggadah text, along with its translation into German by Wolf Heidenheim. It is the twentieth edition of the Roedelheimer Haggadah that first appeared in 1822/23, there with the German translation in Hebrew characters. In 1839, the translation first appeared in Roman letters, as is the case with our new acquisition.

There is, to be sure, nothing remarkable about this edition from 1848. → continue reading