Nina Wilkens contemplating the collage “Found objects on flat cardboard box” on her computer screen; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Svenja Kutscher

Five black and white photographs of a scantily-clad woman, legs spread open, in various suggestive poses. The pictures smudged and stuck askew onto white cardboard. On top, a Star of David partly smeared with yellow paint. A brown dildo is fastened next to the cardboard. This constellation of things looks at first glance like useless trash. Objects left on the ground, covered with their share of grime, and now lying here piled on top of one another. This work by Boris Lurie from our current exhibition “No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie” (further information about the exhibition on our website) has no name and its date is ambiguous.

When I started thinking, around a year ago, about a pedagogical program on Boris Lurie, I got stuck on this picture as I sat at my computer clicking through images of the works that were being considered for the exhibit. I was confused by my own reaction to this collage of two- and three-dimensional objects: vacillating between disgust and uncertainty. I had the words “obscene” and “tasteless” on the tip of my tongue but found them unsuitable. The image hurt. I wondered how students would react to Boris Lurie’s art. → continue reading

“Something happened there to which we cannot reconcile ourselves. None of us ever can,” said Hannah Arendt with regard to Auschwitz and its repercussions during a now legendary TV interview with Günter Gaus. A two-minute excerpt from that encounter serves today in our permanent exhibition as introduction to a film installation concerning the Auschwitz Trial (cf. this blog entry about the reopening of that part of the exhibition in summer 2013).

“Something happened there to which we cannot reconcile ourselves. None of us ever can,” said Hannah Arendt with regard to Auschwitz and its repercussions during a now legendary TV interview with Günter Gaus. A two-minute excerpt from that encounter serves today in our permanent exhibition as introduction to a film installation concerning the Auschwitz Trial (cf. this blog entry about the reopening of that part of the exhibition in summer 2013).

In our exhibition of the work of Fred Stein in 2013/14 we presented photographs inter alia of the political theorist Arendt herself, as you can read in our blog and on the exhibition website.

Hannah Arendt is a major influence also on contemporary artists: Alex Martinis Roe, in the work she produced for our art vending machine, “A Letter to Deutsche Post,” demanded a re-issue of the postage stamps bearing Arendt’s portrait (cf. our interview with the artist in this blog). Also, a symposium held at our museum last December drew on the work of Hannah Arendt as a springboard for discussion of the current significance of pluralism in theory and practice (cf. the topics addressed there, as listed in our events calendar).

Philosophie Magazin has just devoted a special issue to this exceptional thinker. Titled Hannah Arendt. Die Freiheit des Denkens [Hannah Arendt. The Freedom of Thought], on the newsstands as of 16 June. → continue reading

A Conversation with Peter Weibel about whether Boris Lurie Should Be Seen as a Part of the Ultra-realist Neo-avant-garde, and Pornography as a Metaphor for Capitalist Society

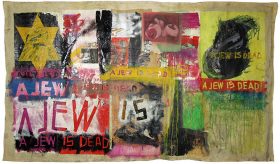

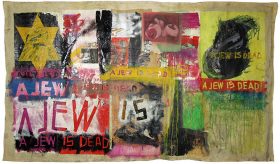

Boris Lurie, “A Jew is dead,” 1964; Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York, USA

Mirjam Bitter, blog editor: As part of the program accompanying our Boris Lurie retrospective, you’ll be giving a lecture at the Jewish Museum Berlin on 30 May 2016 on the subject of “The Holocaust and the Problem of Visual Representation,” (further details of which can be found in our events calendar). Is this tied up with the idea that the Holocaust is a major theme in Lurie’s work?

Peter Weibel

© ONUK

Peter Weibel: The Holocaust, along with war, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki were pivotal traumatic experiences for the post-Second World War neo-avant-garde. Take, for example, Yves Klein’s painting “Hiroshima” (1961) or Joseph Beuy’s environment “Show Your Wound” (1974–1975). Many artists responded to the inhumanity they had witnessed by calling into question humanity and indeed, civilization itself: Why, they asked, had literature, painting, music, and philosophy been unable to prevent this twentieth-century barbarism? → continue reading