View from the Academy of the Jewish Museum Berlin towards the Springer building with the lit-up sign, #FreeDeniz; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Stefanie Haupt

As I leave my office at the Jewish Museum Berlin, emerging from the W. Michael Blumenthal Academy onto the street, the hashtag “#FreeDeniz” beams towards me from an illuminated black-on-turquoise-green display on the Axel Springer building. The first time I saw it, I was cheered by the signal that the publishing house Axel Springer SE* was calling for the release of Die Welt’s correspondent in Turkey, Deniz Yücel. But each day seeing the display has gotten sadder. I’ve known Deniz Yücel since 2003, when — together with other German- and Turkish-speaking Berliners — he organized bilingual protests against the bomb attacks on the two Istanbul synagogues, Neve Shalom and Beth Israel, on November 15 of that year. Twenty-four people were killed in those attacks and at least 300 wounded.

Deniz and I haven’t had contact for quite awhile. But since mid-February, through the news of his imprisonment for “terrorist propaganda” and the car procession protests that followed it, as well as conversations with friends and of course the illuminated sign, memories from the period in 2003 and 2004 when we interacted almost weekly having been coming back. Deniz belonged to a group of friends who recruited me as pedagogical reinforcement for an uncertain project, when I was a newly minted but reluctant teacher from Hamburg. It later became the internationally recognized “Kreuzberger Initiative against Anti-Semitism” (KIgA), arising out of the “Immigrant Initiative against Anti-Semitism,” which had organized a rally for the victims of the Istanbul attacks. “‘We want publicly to proclaim our abhorrence of the terror attack,’ said Deniz Yücel, one of the initiators, since they believe anti-Semitism to be pervasive across Turkish society, and thus also immigrant communities in Berlin” — from the Berlin newspaper die tageszeitung (taz) at the time.

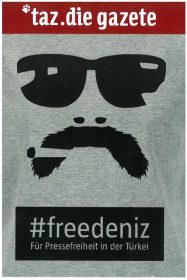

The taz, with these postcards and a bilingual Turkish-German portal at taz.gazete.de, is also advocating Deniz’s release and press freedom in Turkey generally.

Deniz didn’t continue with the organization as it went from an immigrant initiative to one of Kreuzberg (one of Berlin’s most diverse districts) generally but as a flat-mate and close friend, he was always around, from the development of the concept to the acquisition of means, the first implementation of projects with real partners and actual youths to new motions, fights, and the publication of results. As a writer for Jungle World, taz, and Die Welt, with many contributions on social media as well, Deniz had his own positions and convictions about what we were doing — and we returned the favor: “You can’t run to the office for integrating foreigners and make ‘the Turks’ or ‘immigrants’ out to be the biggest anti-Semites!” — “German-Turkish.” — “Why not Turkish-German?!” — “Now the Islamists are gaining the upper hand. We have to oppose it ourselves!” — “Civil servants responsible for integration should be removed altogether, we shouldn’t work with them.” — “Islamist types are also German, I mean without Turkish or whatever else before it.” — …and so on, to give you an idea of us sitting around our kitchen table on Mariannen Straße.

After I left the Berlin project, our contact tailed off, though Deniz encountered me oddly enough in the scholarly literature. Immigration researchers like to seize on experiences like the memory of a particular teacher, particularly to illustrate everyday and institutional racism in the cases of “successful immigrant children”: “when I was the only one in the class who could answer her question about some low Hessian mountain range, she shouted at the class: ‘You guys should be embarrassed, the Turkish boy knows this better than you!’” (see taz)

Knowledge of German geography doesn’t make you German, and the language gets used as a boundary marker, especially when you know better and ironically place yourself ‘above’: for example the expression Deniz often used, “wo gibt” (that there is, as in, the best that there is) is being used in “Land mit freiste Presse wo gibt” (country with the free-est press that there is) (see Facebook), and then here in Der Spiegel being described erroneously (if benignly) as “an immigrant-influenced coloring of the German language.” My German teacher was already warning us in the mid-1980s about the colloquial and even dialectal “wo” (where) being used as a relative pronoun (that). And this was at a time when immigrants didn’t have much of a voice in public. Just use the quickest inflection form — the whole thing with the correct German cases is a little long for Twitter — and suddenly you’re the Turkish boy who had to take “Math for Foreigners” (see taz) at school.

View of the illuminated sign #FreeDeniz from the museum building; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Stefanie Haupt

“Hate Poetry” was an occasion to see Deniz again once I’d moved to Berlin for work in 2012. Those were shows were journalists read racist letters and emails out loud, correspondence they’d received mostly just on account of their names. Aside from insults of all kinds, there were murderous fantasies like “gassing” among other even less friendly threats. Mely Kiyak, Yassin Musharbash, Ebru Taşdemir, and Deniz appeared at the events moderated by Doris Akrap, in various categories of a competition, making the whole thing into an anti-racist party. Sometimes the show turns into a Carnival party with costumes and the paraphernalia of Germans’ actual bogeymen. Deniz would go all in and I half expected him to leave journalism for acting.

Despite, or because of, or anyway with the “feeling that ‘Math for Foreigners’ never ended” (see taz), Deniz is a public Turk and of the view that car processions — with which people are currently demonstrating for his release and gaining good publicity at it (see Tagesschau) — are a core characteristic of the Turkish, or at least those with a “German-” in front (see Jungle World). I can also well imagine which fellow campaigners from our kitchen table days had the idea to protest with car processions. Another friend and comrade-in-arms of old said, on the other hand, that the neo-Nazis in the 1990s were the first to celebrate soccer victories with car processions (which they naturally spelled Autokorsos, the high German plural, rather than Korsi). I’d then have said, listen up, Deniz: “Korso is Italian! And who always wins soccer games?!” Thus, thanks to a dad from Italy I’d get the high fives and the last piece of pizza, explaining how “the plural is Korsi, of course”.

But in addition to processions, we need diplomacy now. Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel considers Deniz to be “a great example of what Germany has achieved in recent years” (see Tagesschau). What remains is to hope not just that Math for Foreigners is over, but also that Diplomacy for Foreigners won’t now begin.

In her current work as a W.M. Blumenthal Fellow on didactic principles for the Middle-East conflict, Rosa Fava regularly draws on her background knowledge about anti-Semitism in Turkey, which Deniz and friends provided her years ago.

↑* Societas Europaea

For current information about Deniz Yücel’s situation, check: https://www.facebook.com/FreundeskreisFreeDeniz/?fref=ts

And to support Deniz, here’s a link to the website: http://freedeniz.de/