On the trail of a coffee shop

It was a very special moment for me when I got to unpack recently a new collection for the Archive. A small package from Tel Aviv lay in front of me. The sender was Mor Kaplansky, an Israeli film-maker, with whom I had been corresponding since spring of this year.

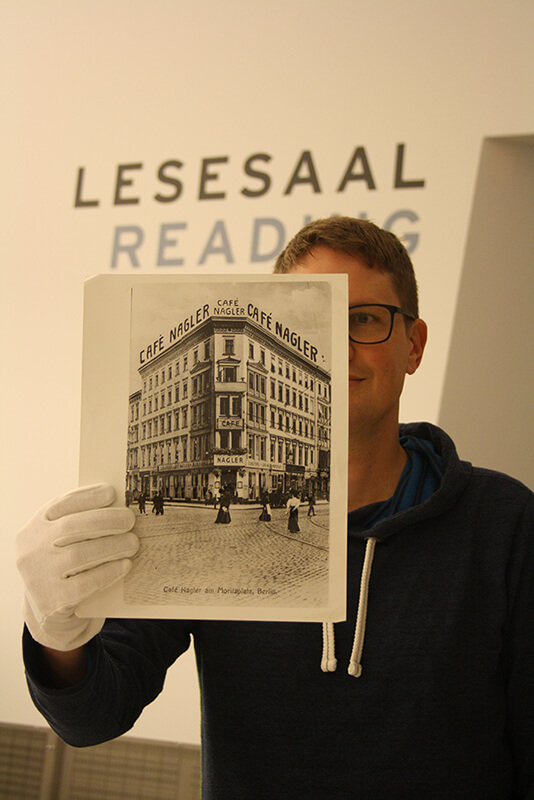

It had all begun in March, at the finissage of Nosh, the Jewish Food Week. In a small café in Kreuzberg, the documentary film Café Nagler had just been shown. The film is about a coffee shop of that name, which had once stood on the Moritzplatz. While in Berlin today, there is no evidence that the café ever existed at the site, descendants of the Naglers in Israel have kept its memory alive right through the present day. The film moved me greatly. I was excited to see on the screen that Naomi, grandmother of the film-maker, had preserved certain treasures such as a coffee service with the emblem of the café and a set of silverware bearing the initials “N”. I also noticed various photographs and documents.

How I would love to be able to sift through this file of memorabilia myself, I thought! As soon as the film’s credits had finished running, I took out my mobile phone and searched for Mor Kaplansky on Facebook. I found her and sent her a message. I congratulated her on the film and let her know that the Jewish Museum Berlin would be very happy if she were to donate any documents, photographs, and other objects pertaining to her family. A few hours later, I already had an answer. Mor told me that her grandmother Naomi had unfortunately just died, but that she almost certainly would have wanted some of her memorabilia of the Café Nagler to return to Berlin: “I would be more than honored to bring some of the Cafe’s artefacts to the museum.”

Since then, Mor and I have stayed in touch. She also connected me with Jon Altman, a relative in Australia. He, too, was immediately prepared to give the Museum some objects on permanent loan. The first package that arrived came from Melbourne.

Signet with the engraving “I. Nagler. Cafétier. Berlin”; Jewish Museum Berlin, on permanent loan from Jon Altman; photo: Jörg Waßmer

Opening it, I found silverware, but also a stamp engraved with the name of the “cafétier” Ignatz Nagler and two lovingly kept baby diaries, dating from 1926 on. A few weeks later, I also received the package from Israel, which held 80 documents and photographs. Mor enclosed an index, in which she had listed the precious contents of the package to the best of her knowledge. As she herself cannot read German, let alone decipher the old German handwriting, she had had to mark several documents with a question mark or the word “unidentified.”

With great joy, I set about making an inventory of the collection. In doing so, I dove into the family history of the Naglers. I accompanied Ignatz Nagler (1870–1929) from Czernowitz (Chernivtsi), then the capital of Bukovina, to the metropolis of Berlin. Here, he worked starting in 1896 in various restaurants and cafés. Based on the letters of recommendation from employers which his family have preserved, I was able to follow his career up to the time at which he became independent and opened his own coffee shop on the Moritzplatz. I held the Naglers’ Ketubah in my hands and succeeded, after clearing a few hurdles, in deciphering the name of the city in which their wedding took place, in 1896: “Krone an der Brahe” was written in a spidery Hebrew scrawl. Ignatz Nagler’s wife Rosa had come from the Prussian province of West Prussia. They had three children, whose birth certificates I also had on my desk. In order to keep an overview of it all, and better understand the kinship ties, I drew a family tree. Only then did I understand how the family branches in Israel and Australia were even related. In perusing the collection, I saw how the big stage of politics directly affected the life of the Naglers time and again – whether on account of military service during the First World War or the loss of their Austrian citizenship after the demise of the Habsburg Empire. I then followed the family’s further journey as they emigrated to Palestine in the 1920s.

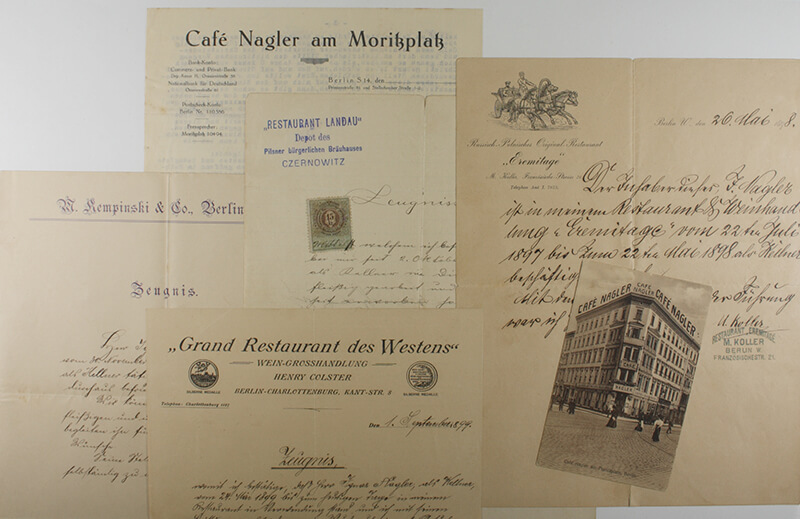

Work references, letter paper, and a postcard; Jewish Museum Berlin, on permanent loan from Jon Altman and the family of Naomi Kaplansky; photo: Jörg Waßmer

Carefully, I studied the surviving photos of the Café Nagler’s interior and tried to imagine how it was laid out spatially. One picture interested me particularly: on it, you see a large banquet hall, extending over two floors, with a balcony along its perimeter. I had my doubts from the very beginning that so grand a hall could have been located within the Café Nagler. After conducting research in various picture databases, I finally solved the riddle! Of course, I had to share the news with Mor right away: “You’re such a detective!”, she wrote back – a message I confess I read with not a little pride.

On 27 November, the Museum will hold a public screening of the film Café Nagler. Mor Kaplansky will be there to answer questions from viewers afterwards. In addition, I shall present a few highlights from the collection – and make public my solution to the mystery behind this intriguing photograph.

Jörg Waßmer very much looks forward to meeting Mor Kaplansky in person.

Naomi war eisern, sie kam bis kurz vor ihrem Tod wöchentlich in das Schwimmbad ihrer Schwiegertochter und nahm am Aerobic Kurs teil. Sie konnte unendlich viele Sprüche, erzählte faszinierend-kurz, eine dominierende Persônlichkeit. Um den Film lässt sich noch viel mehr machen und ich freue mich, dass Sie als Historiker nun vieles ergänzen.