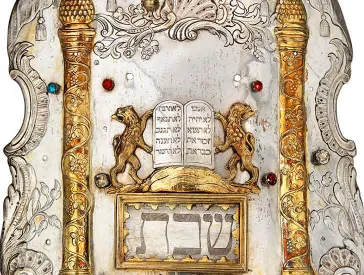

Torah

The term Torah, Hebrew for instruction, refers to the the first part of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), the five books of Moses, and more broadly, to the whole body of religious law.

The Torah contains stories, such as the creation of the world, as well as rules and laws that Jews are supposed to follow. As the Torah was given by God according to tradition, it is considered sacred. In the synagogue, the Jewish place of worship, it is read aloud from a handwritten scroll.