“Decisive Defense and Hard Reparations”

The Financial Punishment of the Jewish Population After the November Pogroms

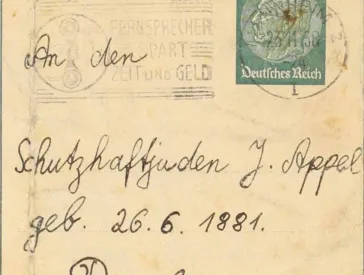

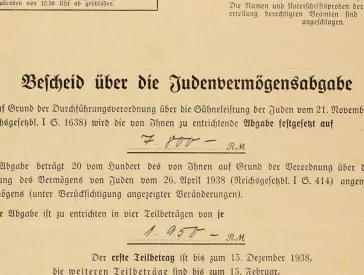

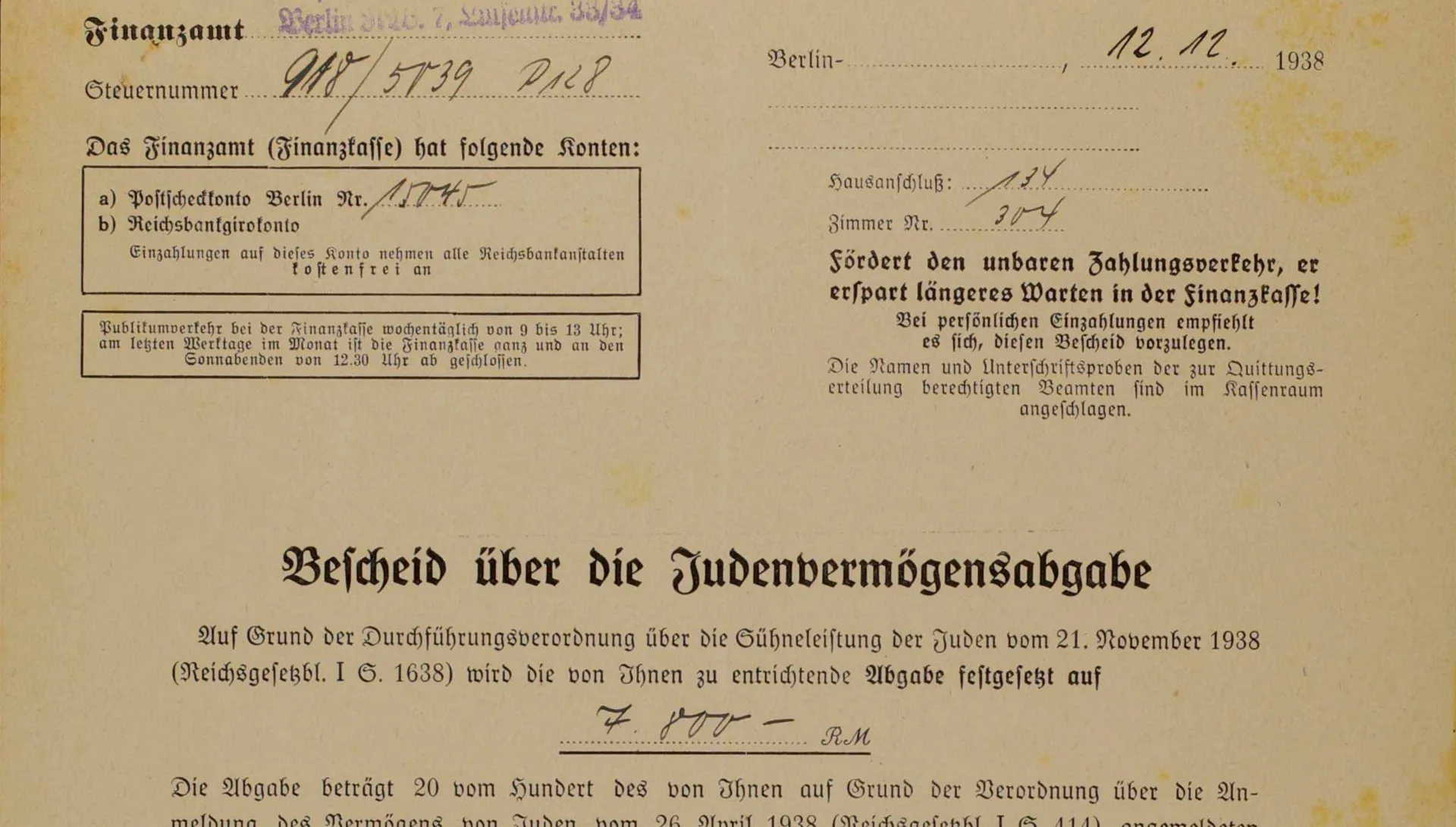

On 13 December 1938, Helene Gumpert received a piece of mail from the tax office in her home city of Parchim. It tersely informed her that she was obligated to pay 2,800 Reichsmarks, which were to be remitted to the tax office in four installments under the Judenvermögensabgabe (Jewish Property Levy). The first installment was due just two days later—on 15 December.

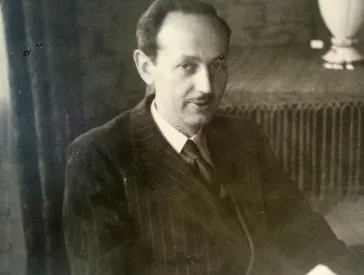

At that point, Helene was 84 years old. She had raised four children with her deceased husband Gustav. Her family had lived in Parchim since at least 1804 and had contributed to the city’s success with a flourishing cloth trade and manufacturing business, carrying its name far beyond the borders of the state of Mecklenburg. After Gustav’s death in 1930, their sons Leo and Rudolph expanded the business to Hamburg. But this glory has long since faded. The cloth factory was “Aryanized” and the Gumpert brothers became ensnared in an agonizing legal battle with the buyers. During the particularly severe riots of Kristallnacht in Parchim, Rudolph was arrested and imprisoned in the Alt-Strelitz prison, while his brother Leo was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Helene stood before the ruins of her life.

Kristallnacht as the Prelude to Financial Pillaging

The November 1938 pogroms (Kristallnacht) represent a break in the lives of German Jews in every sense. For a brief time, the merciless and murderous violence and the destruction of financial entities and religious sites—all of which occurred in a short period of time—marked the sad climax of years of exclusion and disenfranchisement. Those affected by the events of 9 November didn’t have the chance to catch their breath—in short succession, extensive laws and ordinances were passed that were intended to completely deprive Germany’s remaining Jews of the basis of their existence.

Letter from the Parchim tax office to Helene Gumpert, Jewish Museum Berlin, Inv. No. 2005/4/28, gift of the Benjamin family

Already on 12 November, representatives of state offices concerned with “policy on Jews” met under the leadership of Hermann Göring. At the end of the conference, after a contentious discussion, they had established the “Ordinance on Reparations by Jews of German Nationality” (Verordnung über die Sühneleistung der Juden deutscher Staatsangehörigkeit). Two days later, the ordinance, a mere two paragraphs long, was published in the Reichsgesetzblatt (Reich Law Gazette), rendering it legally effective. The wording is brusque:

“The antagonistic stance of the Jewry toward the German people and Reich, which does not shrink even from cowardly acts of murder, requires us to stage decisive defense and require hard reparations.”

According to the lawmakers’ interpretation, these reparations could only be made with money—together, all of the Jews in Germany had to raise one billion Reichsmarks and pay it to the Reich. The Reich Ministry of Finance would soon decree instructions for implementation of the payments.

The State’s Acute Need for Capital

Plans for extraordinary taxes that would apply only to Jews had existed for a long time, but for various reasons, until this point they hadn’t reached the implementation stage. But in fall of 1938, an opportune political moment arose—the assassination of Legal Consul Ernst von Rath provided the perfect pretense—just as state finances reached a dire state. Thus, these payments weren’t the transfer of guilt from an individual to the collective, but rather were intended to cover the acute need for cash in the Reich budget, and to help finance armaments. (It is no coincidence that it was Göring who signed the ordinance; he was in charge of the Four-Year Plan, according to which the German Reich was to be economically and militarily prepared for war within four years).

Ordinance on Reparations by Jews of German Nationality, 12.11.1938, RGBl. I 1938, p. 1579

Implementation of the “Jewish Property Levy”

The question of where the billion was to be found was answered in the enactment ordinance of 21 November 1938. Jews of German nationality, as well as stateless Jews with assets of more than 5,000 Reichsmarks were supposed to pay 20 percent of it to their local tax office. The payments were to be made in four increments, each two to three months apart. The first payment was due on 15 December 1938. If the total sum was not paid in these four payments, the officials could demand forfeiture of a fifth payment.

By early December, the tax offices sent the first notices regarding the Jewish Property Levy to the households affected. The offices based their calculations on the level of assets in 1938. It wasn’t even necessary to demand that Jews declare their assets; in April of that year, the “Ordinance Regarding the Registration of the Assets of all Jews” had already required Jews to reveal their financial circumstances to the authorities.

The first goal of this ordinance from the Reich Ministry of Finance was to gain oversight and therefore control of the remaining economic capital. After evaluating the registers, the Ministry estimated that capital of around five billion Reichsmarks could be made available—that is, expropriated—for the German economy.

Those who were determined taxable had no way to object. In a few cases, the decisions were adjusted if the assets had significantly diminished between April and November 1938. In the course of 1939, it was determined that the required sum could only be reached through the payment of a further five-percent installment. Because very few people had the means to pay it, this fifth instalment was often multiply deferred, but it was never waived.

Letter from Leo Gumpert to family members; Jewish Museum Berlin, Inv. No. 2005/4/262, gift of the Benjamin family

“Yesterday we had to spend hours at the bank, where we took care of the first installment of the reparation debt. Hopefully! It was a terrible bit of work, because yesterday there came new stipulations, making the matter all the more difficult.”

Over a Billion Reichsmarks Plus the “Aryanization” of Businesses

Ultimately, the payments exceeded the desired sum of one billion Reichsmarks. The tax office even sent demands for payment to emigrants living abroad. Since the state had long since taken control of their assets remaining in Germany, which were frozen in their accounts, most of the emigrants couldn’t avoid payment.

In total, German Jews had to surrender 25 percent of their assets to the state by the end of 1939. At the same time, their incomes sank to nothing, as the “Law on the Exclusion of Jews from German Economic Life” was passed simultaneously, completing the “Aryanization” of Jewish businesses and effectively prohibiting Jews from any commercial activities by the end of the year. Their precarious financial situation meant that many Jews had to postpone their escape from Germany into the distant future, if it wasn’t prevented completely.

Epilogue ...

After the war, Jews in the Federal Republic of Germany could petition for financial compensation, including for loss of assets due to the “Jewish Property Levy.” It was important to provide documentation as proof for the compensation authorities. The 1938/39 statements from the tax offices suddenly took on a new significance: they were evidence of state-organized plundering.

But for Helene Gumpert there would be no compensation. She died in Parchim in 1941, completely impoverished. Before she died, she had to witness her family home turned into a so-called Judenhaus, from which the last Jews in Parchim were gradually deported to their deaths.

Ulrike Neuwirth, archive

Statement of Asset Registration of Jews for Richard Polack (resident in Paris); Jewish Museum Berlin, Inv. No. 2013/395/77, gift of Orah Young

Citation recommendation:

Ulrike Neuwirth (2018), “Decisive Defense and Hard Reparations”. The Financial Punishment of the Jewish Population After the November Pogroms.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/5971

Online Features: The Background and Ramifications of 9 November 1938 (5)