“Ik neurie mee ’t propellerlied ...”

Het Onderwater-Cabaret: A Testament to Political Resistance in the Occupied Netherlands, 1943–45

Het Onderwater-Cabaret, produced by Curt Bloch, is an impressive testament to individual courage and political resistance. The German-Dutch magazine helped its author and small circle of readers to survive and find a meaning and purpose to their lives.

With living conditions in the Netherlands deteriorating in the spring of 1943, resistance to the German occupiers increased in the broader Dutch population. Small resistance groups formed but in most cases were not in touch with one another. They included the Amsterdam-based group De Ondergedoken Camera (The Underground Camera), which documented the activities of the German occupiers in photographs between 1943 and 1945.1 Among the Jewish exiles living in hiding, there was a growing sense of powerlessness, a feeling that they had lost the ability to act and were no longer capable of a self-determined life.

In some cases, the resulting question of how to regain the capacity for individual and collective action led to artistic activity in isolation. The artists documented events, gave a small circle of likeminded individuals renewed strength to carry on, and took a stand against political developments.

The underground magazine Het Onderwater-Cabaret (OWC, The Underwater Cabaret) had its origins in these experiences. Curt Bloch, a German-Jewish exile who held a doctorate in law and later worked as an antique dealer, “published” his first self-made issue in his hiding place in Enschede, the Netherlands, on August 22, 1943.2

Who is Curt Bloch?

Curt Bloch (1908–1975), German lawyer and author of the handmade underground magazine Het Onderwater-Cabaret; pseudonym Cornelis Breedenbeek; fled to the Netherlands in 1933; in hiding there from August 1942 onwards

The First Issue of the OWC

This magazine’s first issue was eighteen pages long and featured a self-designed front cover and a list of credits on the back with an advertisement for a book for young adults written by Bloch. The introductory table of contents is followed by three poems in Dutch, “Vroeger, thans en straks” (Earlier, Now, and Soon), “Groote mannen” (Great Men), and “Spoken: Een griezelig verhaal” (Ghosts: A Spooky Story).3 These pieces deal with the misery of everyday existence under German occupation, the lack of fuel and food, and – captured in nightmarish images – the psychological strains of a life in hiding. Bloch sharply criticized Hitler and Mussolini as upstarts who were propelling their deluded nations into a war that would only end in defeat. The political events on the Eastern Front and in Italy, up to Mussolini’s fall in July 1943, nourished the hope of a quick end to the war among those living in hiding. These events also form the historical backdrop to the fourth poem in the first issue, the only text written in German.

Its title, “Der Schleier von Catania” (The Veil of Catania), evokes the story of Agatha of Sicily, whose veil was said to be able to stop Mount Etna from erupting. In a satirical reversal of this image, the poem attacks Goebbels’ propaganda and cover-up tactics, which reinterpreted the surprise landing by the British Eighth Army and the US Seventh Army on Sicily on July 10, 1943, and the relatively easy capture of Catania as part of the German war strategy. In this way the propaganda concealed the true course of the war. Bearing the note “Für das 4e Reichs-Cabaret” (For the Cabaret of the 4th Reich), the poem introduced a section of the magazine that presented poems exclusively in German and would become an integral part of the OWC. Taking a satirical and often sarcastic tone, Bloch revealed the absurdities of German propaganda in cabaret style.

The fifth poem in the first issue, also in Dutch, reads like a manifesto for the underground magazine as a whole. It is titled “Het Propellerlied” (The Propeller Song) and is dedicated to the military struggle. With the Royal Air Force bombing Hamburg and the Ruhr region, the lyrical subject attempts to liberate himself from his desperate, gloomy situation in hiding through the act of writing:

Is soms mijn moed erg diep gezonken,

Kijk ik de dingen somber aan

En hoor dan met motorenronken

De RAF. naar Duitschland gaan.

(When my spirits have plunged to the depths,

And the world looks so gloomy and grim,

I’m relieved by the plane engines’ drone

RAF flying Germany-bound.)

The sounds of the military action and the associated hope of crushing the “Third Reich” bring the lyrical subject “relief from his suffering.” He hums along to the propeller song and becomes part of the community-building “we” of the Allies’ military struggle. At the same time, he does not lose sight of the ambivalence of his desire for resistance and its possible realization.

Ik neurie mee ’t propellerlied:

Wij vliegen met gezoem, gebrom,

Of ziekenhuis, of Keulsche Dom,

Het wordt verbrijzeld door een bom,

Of een fabriek of burgerhuis,

Wij slaan het Derde Rijk tot gruis.

(I hum along to the propeller song:

We fly by with a whirr and a purr

Whether hospital or Cologne Cathedral

A bombshell will blast it to bits,

From factories to tenements,

We will slice the Third Reich into slivers.)

The Dutch phrase “Tante Betje” (Aunt Betsy) is a play on words, referring not only to a real person but also to a stylistic error involving an incorrectly inverted sentence element.4 In the poem Bloch creates a parallel between such errors and the “inverted” views of the character. In the final stanzas, the lyrical subject calls on Tante Betje, who is frightened by the engine noises, to learn from his experiences and recognize that her fear of the bombers is an “inverted” way of looking at things. As a proxy for the poem’s imagined readers, she is told not to fear the engine’s hum but to cheerfully welcome it and share her new perspective with others – and in this way to join the resistance.

Daar moet ik zeggen, Tante Betje

Ik vind je standpunt heel verkeerd

Je moest het vinden een verzetje

Ik wou, dat je dat van me leert:

Hoor jij des nachts motoren brommen

En het beneemt je dan den slaap,

Denk dan, het kan me niets verdommen,

Zeg vroolijk tegen Oome Jaap:

Zij vliegen met gezoem, gebrom,

Of ziekenhuis of Keulsche Dom

Of het wordt verbrijzeld door een bom,

Of een fabriek, of burgerhuis,

Zij slaan het Derde Rijk tot gruis.

(I must tell you, Auntie Betje,

You are seeing it all upside down,

You should greet it as amusement

How I wish you would learn that from me:

When you hear engines humming at night

And the buzzing sound robs you of sleep,

You should think “I’m not troubled at all,”

And then cheerfully tell Uncle Jaap:

They fly by with a whirr and a purr

Whether hospital or Cologne Cathedral

A bombshell will blast it to bits,

From factories to tenements,

They will slice the Third Reich into slivers.)

A Chronicler in Hiding

At the start of his project, Bloch could probably never have imagined that as the sole editor and author of the OWC, which ran for ninety-five issues and covered more than 1,000 pages, he would ultimately serve as the “chronicler”5 of the war from August 1943 to his liberation in Borne on April 3, 1945. Although the look and design of the publication evolved in the weeks and months to come, the thematic focuses of the first issue and the use of collages on the front cover did not change. In late December 1943, Bloch also began integrating newspaper clippings into his texts,6 which from January 1944 on grew longer and more comprehensive.

“De spekballade” (The Bacon Ballad), excerpt, Het Onderwater-Cabaret from 30 August 1943; Jewish Museum Berlin, collection/816, Curt Bloch Collection, gift of Charities Aid Foundation America, thanks to the generosity of the Bloch family

Even in the later issues of 1943, poems such as “De spekballade” (The Bacon Ballad, August 30, 1943) and “Het fruitsprookje” (The Fairy Tale of Fruit, September 4, 1943) repeatedly address the difficult situation and life in hiding – a topic that is impressively illustrated on the covers of the first two issues. The initially comical or optimistic nature of these texts, including “De spekballade” about attempts to secure food, increasingly give way to poems that explore the impoverished life in hiding.

These poems reflect the sense of despair over dashed hopes of liberation and also describe the fears and grueling wait in hiding. In “Der neue Prometheus” (The New Prometheus) in the issue of October 14, 1944, the situation in hiding is compared to the never-ending torture of Prometheus. In the final awkward cross-rhyme of the poem, the danger of writing itself becomes the focus.7 The poem “Afscheid van het OWC” (Farewell to the OWC) in the issue of April 15, 1944, also shows the difficulties of sustaining the journal project over such a long period of time, with no change in sight for those in hiding. During this period the poet felt resigned and exhausted. Doubt had been cast on his conviction that the war could be treated in a satirical burlesque fashion, plunging him into crisis. In the poem he announces the end of Het Onderwater-Cabaret:

Afscheid van het OWC

Wij wachten nu al maanden lang,

Dat ergens iets geschiedt,

Wij willen vrij uit ons gevang,

Want langer kan het niet.

. . .

Men ziet geen eind, men ziet geen slot

En geen vooruitzicht meer

En voor dit feit verstomt ons spot,

De tijd drukt ons terneer.

(Farewell to the OWC

We’ve been waiting for months,

For something to happen.

We want to be liberated from our captivity,

Because it is no longer tolerable.

. . .

We see no end or conclusion;

We have no prospects.

In the face of this, we fall silent with our ridicule,

Time weighs heavy on us.)

Despite the Allies’ successes at the front, the war continued and living conditions in the Netherlands worsened dramatically. By September 1944, the deportation of Jews from the country was almost complete. The famine that broke out that winter caused severe existential hardship for the entire population. The conditions for the writer, who suffered from hunger and cold, were reflected in the design of his magazine. In final months of the war, Bloch's handwriting became increasingly illegible, and from January 1945 on, he wrote his poems in block letters only.

His personal verses, dedicated to his mother Paula and his sister Helene, also show how difficult it was to remain confident in the face of the events of the war, the deportations, and the hunger. Bloch’s birthday poem “Voor Moeder (14 April)” (For Mother [April 14]), published in the issue of April 8, 1944, sounds fearful in places: “kleine kans, / dat men elkaar naar [sic.] afloop dezer tijden / Nog eens in leven wederziet” (“Small chance / that we will see each other alive again / once this period is over”). Like Bloch’s younger sister Helene, Paula Bloch was betrayed in early 1943, arrested in her hiding place in Leiden, and deported to Sobibor via Westerbork. Bloch’s personal poems, which express his concern about the two women and grief over his failed attempt to protect them, occupy a special place in the OWC. Among them are four poems in the second issue of the OWC, which was titled “Hallo Yvonne!” and published on August 30, 1943 – Helene’s twentieth birthday. They address her as “Yvonne” (the name she adopted in hiding), “Leni,” and “Schwesterlein” (Little Sister). To avoid complete despair, the lyrical subject clings to the unsupported hope of a “deus ex machina” despite his knowledge of the “Nazigruweldaden . . . massamoord en massagraf” (“Nazi atrocities . . . mass murder and a mass grave”) in Eastern Europe.8 Nevertheless, his exclamation that “Polen is nog niet verloren” (“Poland is not yet lost”) is tinged with despair.9 The lyrical subject attempts to give strength to his absent sister – and above all to himself – and encourage her to persevere:

Houd moed und blijf vertrouwen

En tracht om elke prijs in ´t leven je te hoûen,

Want al het andre komt terecht.

(Remain courageous and confident

And strive to preserve your life at all costs,

Because everything else will fall into place.

(from the poem “Hallo Yvonne!” in the OWC issue of August 30, 1943))

The poems oscillate between knowledge of the arrest of his betrayed relatives, fear for their fate, and a refusal to give up hope for their survival.10

“Voor Moeder” (For Mother), published in the issue of April 8, 1944, recited by Richard Gonlag, 0:47 minutes, in Dutch; Jewish Museum Berlin, Konvolut/816, Curt Bloch Collection, gift of Charities Aid Foundation America, thanks to the generosity of the Bloch family

English translation: For mother

A year went by, a year with no news,

Today I know not, where You are

And yet, I will write a poem for You today,

Since long has it been my habit,

To write a poem for Your birthday

So that’s what I will do once more,

Although it will remain unread for now,

I still hope for that small chance

That once these times come to an end

We will see each other once more in life,

We know not, whereto our fates will lead us

And whether a happy end awaits us, or not.

Today we don’t rejoice with birthday celebrations,

Those belong to times long past,

Today I merely wish to thank you, Mother,

For everything You have ever done for me.

The OWC as a Political Project

Despite these impressive accounts of personal fates, the individual experiences recounted in the OWC tend to recede behind a satirical political examination of fascist Germany and the consequences of the German occupation of the Netherlands. Most of all, the OWC appears to be a political project written from an antifascist socialist perspective.

In the poem “Der Novemberling” (November Child) in the issue of December 11, 1943, the author links the lyrical subject’s birthday to political events in past months of November. He describes the lyrical subject as “infected” by the revolution and as an antifascist, socialist poet:11

Ich fühle mit der Masse,

Begreife ihre Not

Und darum bin ich heute

Politisch ziemlich rot.

Hab‘ ich auch heute Sorgen,

Ich achte sie gering

Ich glaube an das Morgen,

Ich bin Novemberling.

(The masses and their plight

Have won my sympathy

And that is why today

I’m red politically.

Though I do worry now,

I rate my fears as mild,

And hold tomorrow high

As a November child.)

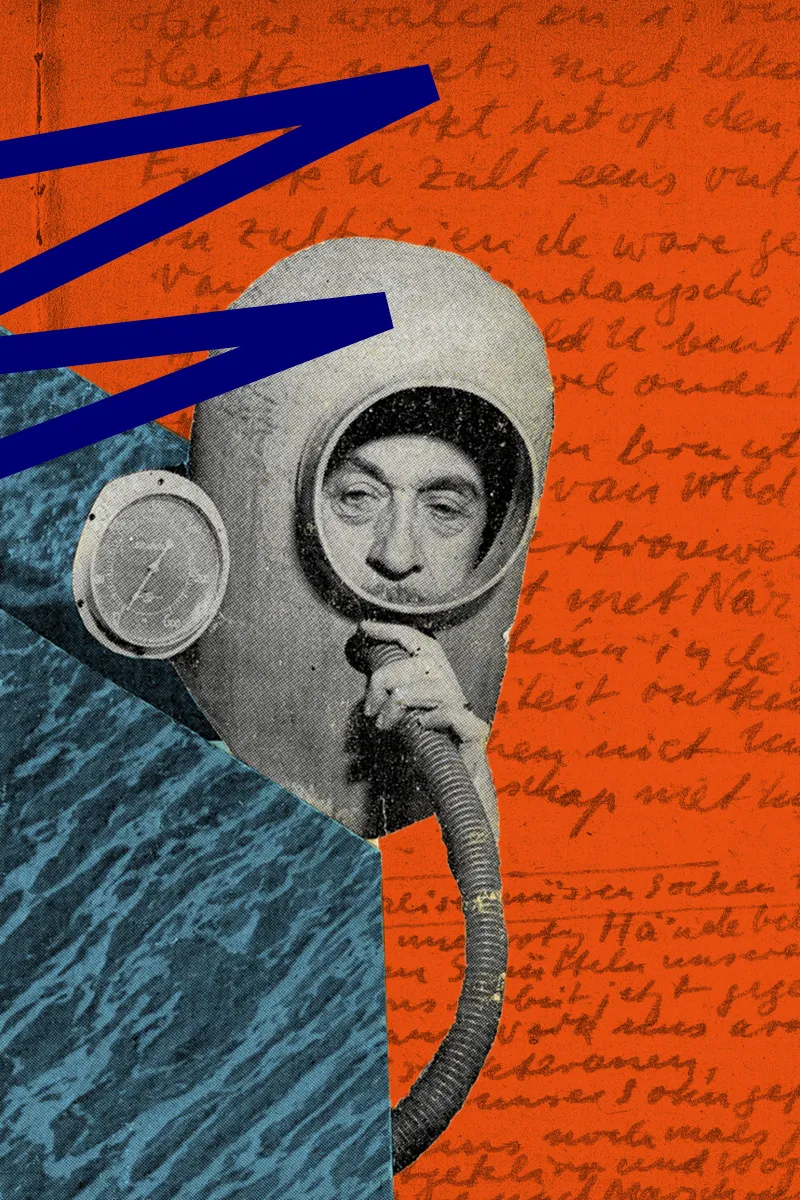

Cover of the OWC issue of 31 December 1944; Jewish Museum Berlin, Konvolut/816, Curt Bloch Collection, gift of Charities Aid Foundation America, thanks to the generosity of the Bloch family

In the first issue of January 1945,12 the lyrical subject of the poem “De Verzetsbeweging” (The Resistance Movement) also adopts the perspective of the resistance fighters, which informs most of the OWC. He does so by describing the governments of Georgios Papandreou in Greece and Hubert Pierlot in Belgium as pseudo-democracies. The broader context is the disputes between the Allies, their partners, and resistance groups over the formation of legitimate governments in the liberated states.

In the initial months of the OWC’s existence, a series of programmatic poems illustrated the main ambitions Bloch pursued with the project. In “Het Onderwater Cabaret” in the issue of December 18, 1943, Bloch not only positions his magazine as “red politically,” but also claims – in contrast to other publications from the period – to be spreading the truth freely and independently, publishing what could no longer be read in other papers, and providing antifascist education. In the issue of January 29, 1944, the poem “Ein Ziel” (A Goal) explicitly formulates this aim, stating:

So hat mein Dichten einen Zweck:

Die Hirne zu laxieren

Und Göbbels Propagandadreck

Aus ihnen abzuführen.

(In this sense my poetry has a purpose:

To administer a laxative to people’s brains

And to purge them of

Goebbel’s filthy propaganda.)

In the context of the war, the OWC presented the atrocities for which the Nazis and their followers were responsible as well as the contradictions between these atrocities and the propagandistic statements about them.

For example, the poem “De ‘bevoorrechten’” (The “Privileged”) in the issue of September 4, 1943, initially portrays the self-image of Nazi supporters, who see themselves as the privileged bearers of an unbending ideology (“als van staal” – “as if made of steel”) and as the future beneficiaries of an imminent victory. The poem then undermines this perspective twice in the text. At the start of the poem, this self-conception is characterized as misguided through a comparative presentation of parallel images: it is connected to the conviction mentally ill patients have of being “enlightened” and compared to the way visitors to a zoo perceive the monkeys there as ugly. In the last stanza, this self-image is also explicitly rejected as wrongheaded:

Jij bent voorbarig, jonge kwast,

Zou jij ook maar iets verder kijken

Dan zou het lot, waarnaar je vlast,

Je zeker niet meer zoo ‘bevoorrecht’ lijken.

(You are a hasty young fool.

If only you would look a bit further,

Then the destiny you are eager for

Would certainly no longer seem privileged.)

The often satirical confrontation between Nazi and resistance perspectives can already be found in the magazine’s first issues and continues in the poems that incorporate newspaper reports. This strategy is all the more persuasive because in these reports the Nazis are given the opportunity to speak in their own voices. Their position does not take literary form, as in “Der Schleier von Catania” or “De ‘bevoorrechten,’” but is literally present in the newspaper documents themselves.

This technique of a confrontational collage is exemplified by the poem “Oude kranten” (Old Newspapers) in the issue with the same title from January 22, 1944.

Oude kranten

Een zeldzame bekoring

Geeft mij een oude krant

Men kan er veel uit leeren,

Hij is interessant.

Je kunt eraan goed merken,

Hoe gauw de tijd vervliegt,

En buitendien blijkt duidelijk

Hoezeer men ons beliegt.

(Old Newspapers

To me, an old newspaper

Is oddly captivating

It has so much to teach,

It’s truly fascinating.

Inside, it’s clear to see,

How rapidly time flies,

Besides, it plainly shows

How much we’re fed with lies.)

Initially without comment, Bloch supplements the poem with a Dutch newspaper report from September 25, 1939, containing a declaration by Goebbels and a resolution by the German government to strictly respect the sovereignty of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

These propagandistic lies are paraphrased in the texts and ultimately exposed as falsehoods by a reference to the actual course of the war:

Er kwam wel krijg met Rusland,

Amerika kwam ook

En de krantenillusies

Zijn opgegaan in rook.

(The war with Russia came,

America came, too,

And the newspaper illusions

Went up in smoke.)

A perspective denounced by Nazi propaganda as “gossip” thus turns out to be true.

In addition to providing encouragement to the small circle of readers and reducing the mental strain on the author through creative political work, the OWC aimed mainly to provide information about current political events. The magazine did so in two ways: First, the texts attack the ideology and practices of the fascist regime in Germany and the occupied Netherlands by countering its propaganda with a debunking, educational perspective (not least in the German-language section “Cabaret of the 4th Reich”). Second, the poems take aim at the Dutch collaborators. The Dutch texts in particular describe the consequences of the German occupation for everyday life.

In this way, the OWC emphatically distances itself from the propaganda of Nazi newspapers such as Volk en Vaderland and attacks the cultural activities of the Frontzorg, a department of the NSDAP that sent parcels to Dutch SS fighters on the Eastern Front. In the poem “Proloog voor NSBers en Duitschgezinden” (Prologue for NSB Members and Those Who Think of Themselves as German) in the issue of September 11, 1943, the author combines his rejection of the Frontzorg with a “concern for the inner front”:

Aan “frontzorg” is gewijd dit spel

Als zorg voor het inwendig front

Hekelt het onverbloemd en fel

Of NSB. of Arbeidsfront.

(This game is dedicated to the Frontzorg.

Out of concern for the inner front,

It offers blunt and vehement denunciations,

Whether the NSB or the workers’ organization.)

As in “The Propeller Song,” the OWC constantly adopts the position of the military struggle and the underground resistance. In the poem “De nieuwe service” (The New Service), also appearing in the issue of September 11, 1943, it welcomes the shooting of collaborators by Dutch resistance groups such as the CS-6. The poem “Afrekening” (Settling Scores) in the issue of October 9, 1943, discusses retribution and revenge as ethically justified actions, stating:

Het is geen laag en leelijk wraakgevoel

Dat heden zelfs de vroomste menschen gaat bezielen,

Het is een zuiver hunkern naar gerechtigheid.

(It is not a low and ugly revenge

That today possesses even the most pious of people,

It is pure hunger for justice.)

Several poems sharply criticize the collaboration and corruption of Dutch cultural figures such as Willem Mengelberg, chief conductor of the Concertgebouworkest orchestra. Bloch condemned the concerts given by this ensemble for Nazi functionaries and organizations as a blasphemous service to the “geest van bruut geweld” (“spirit of brutal violence”).13

The OWC’s critique of Rembrandt's ideological instrumentalization by the Nazis was unique in this context and cannot be found in the same form in the underground press or in the Dutch public sphere of those years. While Rembrandt’s personal relationships with Jews and the significance of Jewish figures and biblical themes in his work were highly controversial among Nazis14 – and especially among the SS – Nazi cultural policy in the Netherlands was based on the nationalist veneration of Rembrandt that had existed before the war. It promoted a veritable Rembrandt cult, in which Rembrandt – as a Dutch painter of “Germanic spirit” – became a symbol of Nazi cultural work.15 Alongside various publications and events, his birthday was declared a national holiday and 1944 formed the highlight of a national cultural week. Rembrandt’s house in Amsterdam was considered particularly worthy of protection by the Nazis. The poem “Het Rembrandthuis te Amsterdam” (The Rembrandt House in Amsterdam) in the OWC issue of May 13, 1944, criticizes this cultural appropriation of Rembrandt by arguing that those who claimed to be protecting Rembrandt’s spirit with the house had just destroyed this spirit by deporting the neighborhood’s residents. Thus, at the end of the poem, the Rembrandt House as a symbol of humanity remains suspended in a bitter ambivalence: although it is still present in the city’s old Jewish quarter, where it “defies the madness of the times” (“trotseert den waanzin van den tijd”), the people on whom this humanitas might have been demonstrated were being deported and killed (“weggevoerd en zijn gedood”).

Jewish Experience and Resistance

Apart from the few personal texts discussed above, Judaism, which is one of the themes of “Het Rembrandthuis te Amsterdam,” plays a somewhat subordinate role in Curt Bloch’s poems. The author, who saw himself as an antifascist and stood for a universalist message of freedom and justice, experienced his Jewish heritage primarily in his marginalization, persecution, and life in hiding. He was – as he put it in a poem from September 25, 1943 – a “verstoppeling,”16 for which he playfully combined the words “verstoppen” (to hide) and “verschoppeling” (outcast). In December 1944, when Bloch was forced to leave his hiding place in Enschede and seek refuge with a family in Borne, the lyrical subject once again identifies with the Jewish community through the figure of Ahasverus. He asks, “Wohin wird Euch, wohin wird mich das Schicksal führen?” (“Where will fate lead / For you and me?”).17 This question is posed in the poem “Abschied” (Farewell) in the OWC issue of December 31, 1944. Like “Ahasver” from January 13, 1945, it is one of the few in the magazine to explicitly address the fate of Jews. In both pieces the literary reference to the “eternally wandering Jew” is linked not only to the identification with a persecuted community, but also to the anticipation of the desired liberation and concerns about the uncertain fate of those in hiding. In “Abschied,” the lyrical subject expresses his hope for an end to all suffering18 and the “happy reunion” of a scattered community.

“Abschied” (Farewell) in the OWC issue of 31 December 1944; Jewish Museum Berlin, Konvolut/816, Curt Bloch Collection, gift of Charities Aid Foundation America, thanks to the generosity of the Bloch family

By contrast, “Ahasver” uses the traditional image of the “wandering Jew” who roams from place to place and is “gehöhnt, verfolgt, geschlagen” (“oppressed, derided, beaten”). But it also gives the antisemitic topos a dual oppositional twist. Through the figure the author once again identifies in an explicitly positive way with a Jewish collective as a community of fate. At the same time, the eternal nature of wandering is emphasized by the fact that the community cannot be defeated (“nicht zu besiegen ist”): a life of eternal wanderings means eternal survival. This perspective is further enhanced by reversing another antisemitic topos – that of usury – and connecting it to the announcement of punishment: it is not the Jews but their tormentors who will receive “high interest” for their crimes: “Die Schläge, die ihr gabt, / Kriegt ihr zurück mit Zinsen, / Mit Zins und Zinseszins” (The blows you gave, / You’ll get back with interest, / With interest and compound interest).19

“What Shall Transpire?” The End of the OWC

However, poems such as “Was wird geschehn?” (What Shall Transpire?) in the issue of January 6, 1945, show that people did not remain confident that adequate retribution would be exacted for the fascist crimes. This particular poem expresses concern about what will happen to the Nazis and Hitler after the war. It questions whether the “World Court” will reach the proper verdict and whether there will be vengeance for the Nazis’ actions. When the last issue of the OWC was published on April 3, 1945, the immediate purpose of the magazine had been fulfilled. At the beginning of the project, in the poem “Het Onderwater Cabaret” in the issue of December 18, 1943, Bloch had declared: “als er eindelijk komt de vreê, / Verdwijnt direct het OWC” (“Because when peace finally comes, / The OWC will disappear immediately”).

The direct connection of the texts to current political events, which was evident in all of the issues, ultimately proved problematic not only for the reception of the texts in hiding, but also for the imagined (future) readership, which was to be immunized against political indoctrination through education. Understandably, before the war ended, the magazine was made available only to a small group of helpers and confidants,20 as its discovery would have jeopardized the life of its author and readers.21 But the texts reveal an intended readership of Dutch Nazi followers and a deluded German public, whom they would help reeducate after the war. Bloch discussed the problems and opportunities for future readers in the poem “An meine deutschen Leser” (To My German Readers) in the issue of June 3, 1944:

Und lest ihr sie, müsst ihr nicht denken,

Die sind nun nicht mehr aktuell,

Drum kann man sich das Lesen schenken,

Drum weg damit und möglichst schnell.

Denn amüsant ist die Lektüre

Für manche Leute sicher nicht,

Die sehn, man sitzt hier über ihre

Verfloss’ne Dummheit zu Gericht,

Die Dummheit der vergangnen Zeiten,

Denn die steht grausam hier zu Buch,

Die sie schwer büssten und bereuten

Für ihr Gefühl schon schwer genug.

(And reading them, you mustn’t think

They are no longer relevant,

And merely skim them, swift and quick,

Before you cast my words aside.

Because for certain eyes at least

These words will hardly entertain

To read their past stupidity

On trial within these pages’ court,

Stupidity of times gone by,

Recorded here most gruesomely,

For which they’ve paid a sorry price

Enough already, they will say.)

Ultimately, Bloch’s hopes were dashed that a postwar publication of his poems would help reeducate Germans and Dutch collaborators. Nevertheless, the magazine Het Onderwater Cabaret played an important role in helping the author and his small circle of readers carry on and find a meaning and purpose to their lives. Today the magazine remains an impressive testament to individual courage and political resistance during the German occupation of the Netherlands.

Kerstin Schoor is a professor at the Europa University Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder) and a member of the Board of Directors of the Selma Stern Center for Jewish Studies Berlin-Brandenburg. As a literary and cultural studies scholar, she focuses on topics such as German exile literature after 1933 and German-Jewish literature from the eighteenth to the twenty-first centuries.

Saskia Schreuder teaches at Staring College, a secondary school in Lochem, and is Teacher-in-Residence at the Pre-University College of Society at Radboud University in Nijmegen. Her research centers on German-Jewish literature and she completed her doctorate on Jewish fiction in Nazi Germany.

This article is an expanded version of the essay with the same title in JMB Journal, no. 26, pp. 54-67.

Citation recommendation:

Kerstin Schoor, Saskia Schreuder (2024), “Ik neurie mee ’t propellerlied ...” . Het Onderwater-Cabaret: A Testament to Political Resistance in the Occupied Netherlands, 1943–45.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/10312

- For a more extensive discussion, see the essay by Jeroen Dewulf in JMB Journal, no. 26.↩︎

- The first book about Curt Bloch and his magazine, written by Gerard Groeneveld, was published in autumn 2023 under the title Het Onderwater Cabaret: Satirisch verzet van Curt Bloch. See also the Interview with the author in JMB Journal, no. 26, 89ff. ↩︎

- This and the following translations of excerpts from Bloch’s poems, particularly those of entire verses in English, are included not as poetic renditions but to make the essay more understandable. ↩︎

- The term “tante betje” (also “tantebetje”) was introduced by the language purist Charivarius (1870–1946), who explained that he often came across the stylistic error in letters from his aunt Betje. See https://onzetaal.nl/taalloket/tante-betje. ↩︎

- See the poem “De crisis van het OWC” (The Crisis of the OWC), OWC, December 25, 1943. ↩︎

- The most important source for Bloch’s newspaper clippings was the Twentsch NieuwsbladTwentsch dagblad Tubantia en de Enschedesche courant, De Telegraaf, NRC, Huis aan Huis (probably the Enschede edition), Das Hamburger Fremdenblatt, Münchner Illustrierte Presse, Illustrierter Beobachter, Volk en Vaderland, and Neue JZ. From July 1944 on, copies of Twentsch Nieuwsblad were rationed. Bloch received magazines from helpers to continue his work as a chronicler. See the poems “Krantenbezuiniging” (Newspaper Cuts), OWC, August 5, 1944, and “Bedankje voor geïllustreerde bladen” (Thanks for the Illustrated Papers), OWC, August 9, 1944. ↩︎

- “Wie Prometheus durch die Götter / An den Felsen ward geschmiedet, / Sitz ich hier und fluch und wetter, / Denn ich finde, es ermüdet” (“Just as Prometheus was forged on the rocks / By the gods, / I sit here and curse and thunder, / For I find it tiring”). ↩︎

- From the poem “Nog is Polen niet verloren,” OWC, August 30, 1943. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Curt Bloch did not learn until after the war that his mother and sister had been deported to Sobibor via Westerbork and murdered there on May 21, 1943. His sister Erna Levy was taken to the Stutthof concentration camp in 1944 and died there on October 1, 1944. The news of their deaths plunged Bloch into a deep depression. ↩︎

- See also the poems “Ein Ziel” (A Goal), OWC, January 29, 1944, “Vrijheidslied” (Freedom Song), OWC, September 4, 1943, and “Bloedrood waaien onze vlaggen” (Blood Red Fly Our Flags), OWC, December 18, 1943. ↩︎

- The issue bears no date, but was probably produced in the first week of January 1945. ↩︎

- In “Aan een Verdwaalde” (To Someone Lost), OWC, August 30, 1943. ↩︎

- The poem “Kleiner Rembrandtmonolog” (Small Rembrandt Monologue) in the OWC issue of October 7, 1944, takes aim at the ideologically motivated denigration of Rembrandt's artistic merits by “these colossally stupid fools.” ↩︎

- On the ideological instrumentalization of Rembrandt by the Nazis see Kees Bruin, “Hoe fout was Rembrandt in de oorlog? Over bezit en gebruik van een cultuursymbool,” De Gids 157 (1994): 839–852, here 847. According to Bruin, there was no protest against the ideological exploitation of Rembrandt in the Netherlands during the occupation. The underground press did not comment on it either. ↩︎

- See the poem “Een kleine verstoppeling vraagt” (A Small "Verstoppeling" Asks) OWC, September 25, 1943. ↩︎

- In “Abschied,” OWC, December 31, 1944, see also “Ahasverus in dezen tijd,” OWC, September, 1944. ↩︎

- As the poem „Farewell“ explains: „Daß am Ende dieser Sorgen, / Einmal tagt ein neuer Morgen / Ohne Schmerz und ohne Leid. // Bauend auf den guten Stern / Laßt uns auseinandergehen, / Hoffend, daß nicht allzufern / Winkt ein frohes Wiedersehen“ (“These worries are bygone, / A brand-new day will dawn / And leave all pain behind. / With faith in our good star, / We each must go our way / Hoping that very soon / A happy reunion awaits us.) ↩︎

- See the poem “Ahasver,” OWC, January 13, 1945. ↩︎

- The poem “Het Onderwater Cabaret” in the issue of December 18, 1943, explicitly states that the magazine is only directed at a small circle of readers: “De lezerkring waarvoor het werkt / Is wel zeer klein thans en beperkt, / Maar men begrijpt, het is geen tijd, / Voor al te grote rugbaarheid. / Doch wie tot nu is abonnée, / Is met het OWC tevrêe” (“The readership for which it works / Is currently very small and limited, / But one understands that now is not the time / For too much promotion. / However, those who have subscribed so far / Are satisfied with the OWC”). Among the readers were Bruno Löwenberg and Karola Wolf, with whom Bloch shared a hiding place in Enschede, as well as Bertus and Aleida Menneken, the couple who had taken him in. In Borne he was hidden by Jeronimo and Johanna Hulshof and probably also stayed with other, unknown helpers. For a more detailed discussion, see Gerard Groeneveld, Het Onderwater Cabaret: Satirisch verzet van Curt Bloch (Zwolle, 2023), esp. 47, 62ff., as well as the article by Aubrey Pomerance in JMB Journal 26. ↩︎

- See the poem “Het Onderwater Cabaret” in the issue of December 18, 1943, which warned: “Zorgvuldig houdt met het verstekt, / Men wenscht niet, dat men het ontdekt / Want vindt men het, vriend geloof het maar, / Dan was men werkelijk de sigaar” (“You keep it carefully hidden, / You don’t want it to be discovered / Because if they find it, my friend, / Believe me, you’re in serious trouble”). ↩︎

Exhibition “My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret: Features & Programs

Exhibition Webpage

“My Verses are Like Dynamite” Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret: 9 Feb to 23 Jun 2024

Publications

JMB Journal 26: Het Onderwater Cabaret: Special edition on the occasion of the exhibition

See also

Digital Content

- OWC Online Feature: A Glimpse Behind the Scenes of the Exhibition

- Life and Work of Curt Bloch: Essay with biographical insights, JMB Journal 26

- Hidden in Enschede: Conversation with Contemporary Witness Herbert Zwartz: – Video recording, 16 April 2024, Jewish Museum Berlin, in German

- On the Piano of My Fantasy – Video with Marina Frenk, Richard Gonlag, and Mathias Schäfer, in German, Dutch and German Sign Language

- “It’s Complicated”: A text by Simone Bloch, daughter of Curt Bloch

- Current page: “Ik neurie mee ’t propellerlied…”: Essay on Het Onderwater-Cabaret: A Testament to Political Resistance in the Occupied Netherlands, 1943–45

- Clandestine Literature in the Netherlands 1940–1945: Essay, JMB Journal 26

- All Audio Pieces of the Exhibition with Transcriptions and Translations

- All issues of Het Onderwarter-Cabaret: All 95 issues to browse