Speech for the Presentation of the Dagesh Art Award 2023 for Maya Schweizer

Maya Schweizer, Sans histoire, 2023, video still; © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

Dear Guests,

Dear Dagesh team, dear Friends of the Jewish Museum,

Dear Maya,

“I was thirsty

And I deciphered the cuneiform characters

Then, suddenly, the pigeons of the Holy Ghost flew up in the square

And my hands flew away also, with the sound of an albatross

And these, these are the last reminiscences of the last day

Of the last journey of all

And of the sea.”1

That’s what the Swiss poet Blaise Cendrars wrote in his poem “Prose of the Trans-Siberian” almost exactly 110 years ago. I read this poem at my desk overlooking the cemetery – an often forgotten site of remembrance – and thought of the new work by tonight’s award winner, Maya Schweizer. It’s a film that flashes through your mind and stays with you. How close Cendrars’s descriptions from the past are to Schweizer’s film about future memories.

Exhibition Maya Schweizer: Sans histoire: Features & Programs

Exhibition Webpage

Maya Schweizer: Sans histoire: Dagesh Art Award 2023: Exhibition webpage with information on the exhibited works, 5 May to 27 Aug 2023

Digital Content

Current page: Speech for the Presentation of the Dagesh Art Award 2023: by curator Shelley Harten, for Maya Schweizer, 4 May 2023

See also

- Maya Schweizer: website of the artist

- The Violence We Have Witnessed Carries a Weight on Our Hearts: Dagesh Art Award 2021

- Open, Closed, Open: Dagesh Art Award 2019

- DaDagesh – Jewish Art in Context

Sans histoire – this is the title of both the video work created for the Dagesh Art Award and the exhibition here at the Jewish Museum Berlin. “Without history” – and certainly, at an initial meeting after the prize was announced, the artist talked about the writer Annie Ernaux’s autobiography The Years, in which she describes her life via photos that are not reproduced in the book, and without using the personal pronoun “I.” Unemotionally, Ernaux observes:

“All the images will disappear. ... All the twilight images of the early years, the pools of light from a summer Sunday, images from dreams in which the dead parents come back to life, and you walk down unidentifiable roads. ... The images, real or imaginary, that follow us all the way to sleep – the images of a moment, bathed in a light that is theirs alone. ... They will vanish all at the same time like the millions of images that lay behind the foreheads of the grandparents, dead for half a century, and of the parents, also dead.”2

In her films, Maya Schweizer works with associative streams of images, found footage, collages, materials from her own archive, and spoken or written quotations. When faced with the many impulses, with the fragments of memories that come together in her works, it is hard for the viewer to relinquish control over what is seen. One is tempted to concoct one’s own narrative, to remember stories, instead of tuning into the artist’s clear rhythm and her cinematic demands. As Schweizer says, there is a tension between the mental and the cinematic images in Sans histoire, which, in the style of automatic writing, are juxtaposed and broken yet also interconnected. Schweizer began the first concept paper for the competition with a quotation from Germaine Dulac’s L’art cinématographique: “Cinema slowly revealed to us a new emotional meaning, which already existed in our subconscious and lead us to a sensitive understanding of visual rhythms.”

3

The individual impressions in Schweizer’s work send the viewer down multiple, branching mental paths; sometimes they finish in the dead end of your own memory. It is not worth holding on to the ends of memories. The films, it becomes clear, have their own compass. In her work, Maya Schweizer navigates through sites of remembrance, following traces of forgetting with her camera. She often feels out spaces visually: a city, park, room, garden, or the ocean become receptacles for subconscious impressions made visible through the artist’s attention.

With Sans histoire, Maya Schweizer explores the exhibition space itself as a site of remembrance at the Jewish Museum Berlin. Instead of walking down the thematic paths set by the museum, the artist calls into question general mechanisms of preservation and of storing knowledge in an age characterized by both an explosion of information and simultaneous cultural amnesia.

The social anthropologist Paul Connerton observes how society is trying to escape this paradox by establishing monuments and museums.4 A frequent topos in Maya Schweizer’s work is the embedding of memorial sites in their everyday contexts – what happens to these sites when conscious memory fades into the background?

In reply to the question posed by the art prize, “What now? From Dystopias to Utopias,” Schweizer’s answer is open – sans histoire: both without history and without a story. She confronts a discomfort that is always resonating in society, triggered by current catastrophes and the fear of a potential end of civilization. She addresses fears but also hopes of impermanence that concern both the museum as an actual physical site and major social processes: what happens when memory fades in the face of historical upheavals, climate catastrophe, and, ultimately, the finitude of human existence? Does the past still impact upon the future? Does digital storage halt or encourage an incipient collective amnesia?

Alternating between impulses of threat and liberation, the artist explores trans-human and post-human scenarios in her new film. The exhibition shows a total of four films, situating Sans histoire in Maya Schweizer’s many years of observations of individual and collective memory, which inherently also involves the artist considering forgetfulness.

The presentation begins with L’étoile de mer from 2019. “The Starfish” introduces Schweizer’s experimental cinematic method. The artist submerges herself and the viewers in a sea of memory, which she composes as an associative montage of film clips from her own archive and from movie history, interspersed with texts and sound collages.

In 1901, Sigmund Freud described how waking thought casts dreams aside as alien, distorting them in our memory, or erasing them.5 Schweizer questions this division, creating relationships between mental and filmic images. Through the medium of film, Schweizer navigates the sea as a dream world where what is forgotten becomes just as tangible as what is remembered.

Schweizer repeatedly includes footage of water in her works – a universal symbol of impermanence and forgetting, but also of renewal. In Jewish tradition, ritual washing in the mikveh – a natural pool of water – takes place, for example, after contact with death. In Sans histoire, too, waves and currents sweep away what is shown, getting rid of one image and paving the way for the next.

Representations of boats can be interpreted as a tentative attempt to navigate through the stream of thought. The boats recall the story of Noah’s Ark, the subject of the children’s museum across the street and successor to the first, pre-biblically documented story of humankind: the Epic of Gilgamesh. The epic is about the Sumerian king of the same name and his search for immortality.6 But perhaps this is a dead end?

Maya Schweizer transforms the mezzanine of the Libeskind Building – the architectural center of the museum – into a viewable waking dream of this institution of collection.

With the work Manou, La Seyne sur Mer from 2012, Schweizer adds another concrete examination of her own history to the colossus of memory that is the Jewish Museum. In the film, the artist asks her grandmother about daily life in a retirement home – a conversation the viewers can follow in the form of filmed typing, recalling an archival record. The guided stream of consciousness is punctuated by photos of the grandmother’s room in the home. Maya Schweizer captures memories while simultaneously reflecting on their recording.

The artist skillfully inserts her film in the diagonals of the architecture of the Libeskind Building and activates the area between the Museum’s main staircase, which leads to the core exhibition, and the Memory Void, a reminder of the emptiness created by the Holocaust in Germany. It is telling that even in the Museum, the symbolic place of memory tells no stories. Sans histoire becomes a space to honor remembrance and a monument to forgetting.

The film Voices and Shells from 2020, also shown in the exhibition, captures the unseen in a completely different way and shows traces of collective forgetting. The camera leads from the sewers of Munich – the dark, flowing underground – to the bright daylight of the city’s solid surface. There it scans the façades, uncovering traces of the city’s Nazi history.

Voices are audible and alternate with documentary, self-produced and found footage. There is a repeating motif of a spiral, symbolizing a vortex in time and a recurrence that transmits memories yet also obscures them.

Visitors of the exhibition will discover that the film’s spatial movements happen to correspond to the choreography of a visit to the Jewish Museum. To get to the exhibition, you walk from the bright old building in which we now find ourselves for the award ceremony, through a dark underground passage into the new building, orienting yourself via the axes of the basement, to the large main staircase, which leads to the light. Then, after climbing a floor, a spiral-shaped exhibition circuit is revealed.

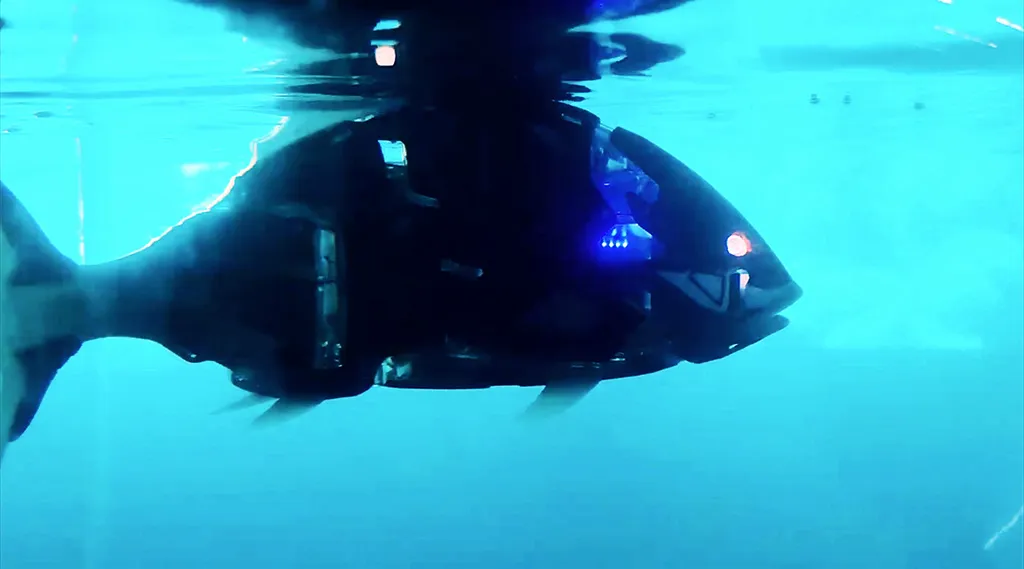

Accompanied by voices and sentences that serve as anchors and sign posts in the maelstrom of associations, the new film Sans histoire also creates a rhythmic change of images between day and night, nature and technology. Representations of a technicized vision of the future, real-seeming robot people, unnerving footage of animals at night and images of people dancing to excess or fleeing from war combine to generate a feeling of discomfort and remind us of an apocalyptic atmosphere that resonates with our subconscious. Footage of the ocean and sleeping elephant seals lolling in the water, a pollen-coated bumble bee, giggling goats and Martian landscapes, on the other hand, are calming. Sometimes, the artist reveals animal characteristics of humans, or points to an archaic state in which humans are redundant. There are formal breaks that prevent a narrative – a history – and also impede memory. Dystopia and utopia alternate.

In the Jewish Museum Berlin, a center of memory, Maya Schweizer speaks of forgetting as a reality conditioned by human beings. In the Jewish tradition, on the other hand, a ritualized engagement with history is an integral component of collective identity. For example, every holiday is linked to a historical event, and the hope of redemption is confirmed annually by reciting, “if I forget you, oh Jerusalem, let my right hand wither.”

In this context, Schweizer’s Sans histoire can be read as an escape from the endless cycle of ritualized remembrance. And yet the reversal, hipuch in Hebrew, is also associated with Jewish ideas of the end times – a time of crisis before the arrival of the Messiah, to which the carnival festival of Purim is dedicated. What now? If redemption comes, history ends. And what remains is “sans histoire.”

Dr. Shelley Harten, curator and orator for Maya Schweizer at the presentation ceremony of the Dagesh Art Award at the Jewish Museum Berlin on 4 May 2023

- Quotation from Blaise Cendrars, “Prose of the Trans-Siberian Railway and of Petite Jehanne de France”, translated from the French by Alan Passes, Modern Poetry in Translation, New Series No. 16 (2000): 172–174; on-line edition published October 2004 by poetrymagazines.org.uk ↩︎

- Annie Ernaux, The Years, translated from the French by Alison L. Strayer, New York: Seven Stories 2017, p. 8–9. ↩︎

- Germaine Dulac: L’art cinématographique, 1927, English version of the quotation translated from a German version in the concept paper for the Dagesh Art Award 2023 by Maya Schweizer. ↩︎

- Paul Connerton, How Modernity Forgets, Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press 2009. ↩︎

- Sigmund Freud, Über den Traum, 1901, in Sigmund Freud, Über Träume und Traumdeutungen, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Bücherei des Wissens 1971, p. 11. ↩︎

- Das Gilgamesch-Epos, translated, commentated, and edited by Wolfgang Röllig, Ditzingen: Reclam 2021.↩︎

Citation recommendation:

Shelley Harten (2023), Speech for the Presentation of the Dagesh Art Award 2023 for Maya Schweizer.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/9985