When a Certificate Was Not Only a Piece of Paper

How Jewish Memory Objects Preserve Chinese History

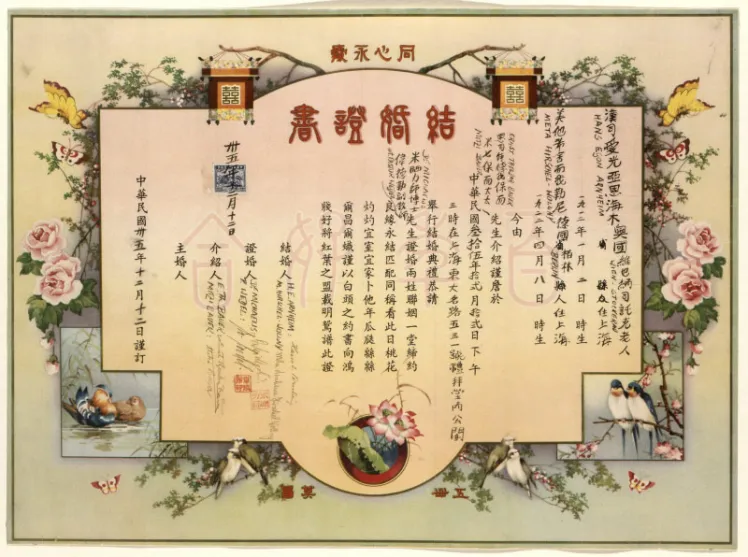

Marriage certificate from Shanghai in Chinese script for Johannes Dombrowsky and Ilse Kussel (1923–1997), 1946; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession Inv.-Nr. DOK 97/15/0, gift of Ayya Khema, photo: Jens Ziehe

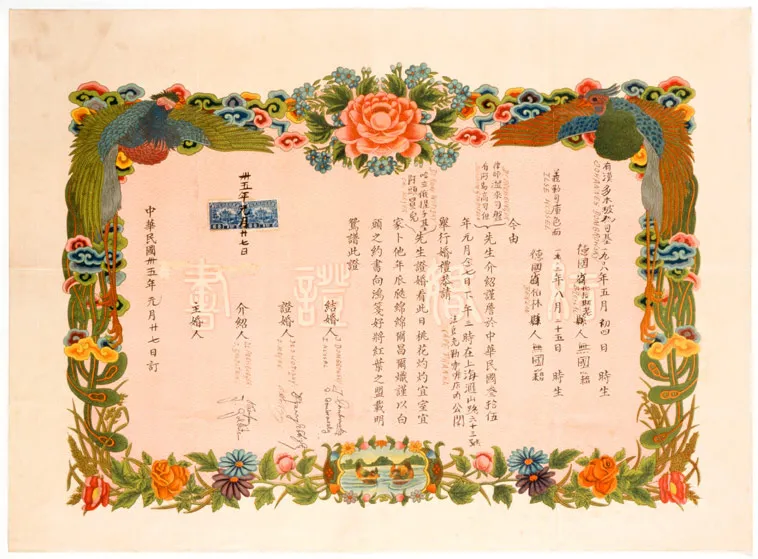

In another essay, I shared my thoughts on some objects from Shanghai in the collection of the Jewish Museum Berlin. Now, I want to draw your attention to a few marriage certificates that caught my eye not just because of their elegant design and well-preserved condition after more than 70 years, but also because I was amazed how Chinese cultural elements had entered and influenced the life of Jews who fled the Nazi rule, even though the Jews largely maintained their own cultural and educational activities in Shanghai with newspapers, Jewish schools, concerts, sport activities, theaters (e.g. Delila, Nathan der Weise, etc.), and parties (e.g. a not so sober celebration of Purim).

In today’s China, a certificate of marriage is simply a passport-sized piece of paper with plain text in black and white. With a divorce rate soaring to all time high and more and more young Chinese people choosing not to marry, this piece of paper actually has little meaning except when it is used to divide properties in divorces.

Chinese marriage certificate for Irma Bielschowsky (1902–2000) and Albert Elias Less (1887–1952), 1944; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2003/174/4, gift of Gert and Brigitte Stroetzel

With the rapid change of society and the degradation of traditional values faced by China today, more and more young Chinese feel nostalgic towards the period of the Republic of China. After the collapse of Manchu rule in 1912, the newly established Chinese republic was trying to adapt itself to modern civilization. For a long time, China was in political chaos, while culturally and intellectually it was enjoying unprecedented freedom and prosperity, especially compared to the first 30 years of communist rule after 1949.

The certificates of marriage from Shanghai I found in the Jewish Museum Berlin’s collection are decorated with traditional and modern elements and were apparently designed to meet the taste of the new generation of Chinese, who were enjoying more and more freedom and made marriage for love a common urban practice in the early 20th century. These certificates are a witness to a time in Chinese society. They are particularly valuable because not many such objects have survived after the numerous wars and revolutions over the last 70 years (especially the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”).

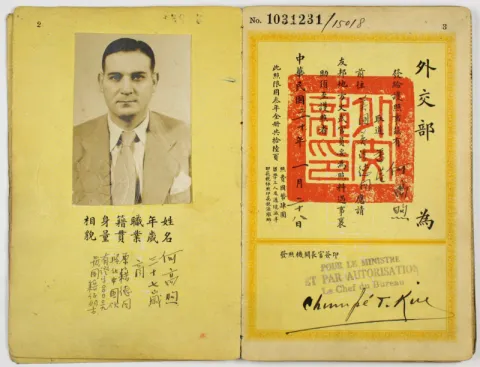

Chinese marriage certificate for Meta Hirschel-Wollny (1922–2000) and Hans Egon Arnheim, 1946; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 1999/253/0, gift of Meta Schiowitz, photo: Jens Ziehe

One of the certificates dates back to 1944 and the other two to 1946. From the two certificates from 1946, we know where the couples were from: the first from Vienna and Berlin; the second from Breslau, Germany (though by that time this city had already been transferred to Poland) and Berlin. These certificates contain an abundance of Chinese symbols: the Chinese dragon (power and good luck), the Chinese phoenix and peony (harmony and prosperity), the Chinese magpie (good fortune and happiness), two mandarin ducks (wedded bliss and fidelity), two butterflies (pursuit for love and freedom like in the legend “butterfly lovers”), the lotus flower (nobility and purity), the peach flower (romance and vitality), and others.

The blessing on each certificate is written in a poetic style containing romantic quotes and allusions from “Classic of Poetry” (c. 600 BC) and Tang poems (c. 7-9 Century AD).

For today’s Chinese people these certificates could serve as a reminder of the importance and traditional values of marriage and family.

After doing some research into the names on the certificates, I found a sad story related to Hans Egon Arnheim (listed on the 2nd certificate). Before his wedding in 1946, he and his fiancée Henny Pia (also from Vienna) escaped Nazi occupied Austria in June 1939 and came to Shanghai together. However, when Henny failed to convince her mother Ella Herzer-Königsberger to join them in Shanghai, she returned to Vienna and disappeared without a trace (Karin Ploog: …Als die Noten laufen lernten…Teil 2: Geschichte und Geschichten der U-Musik bis 1945 Komponisten – Librettisten – Texter, p. 349).

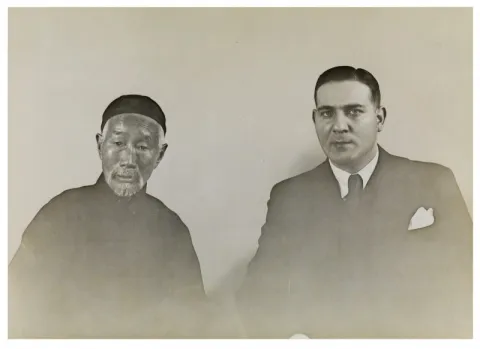

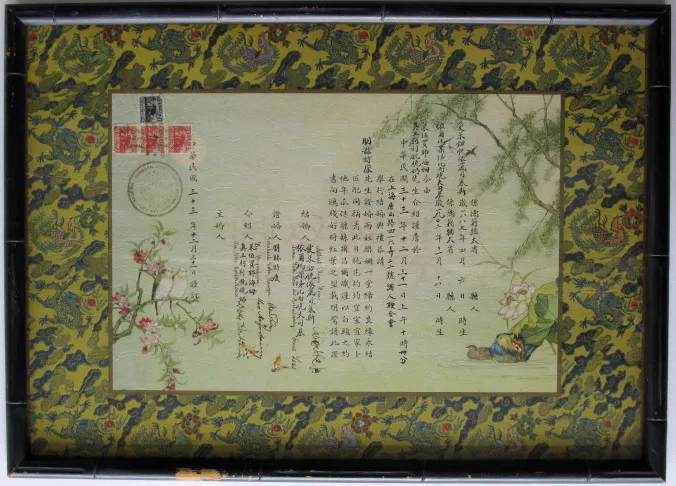

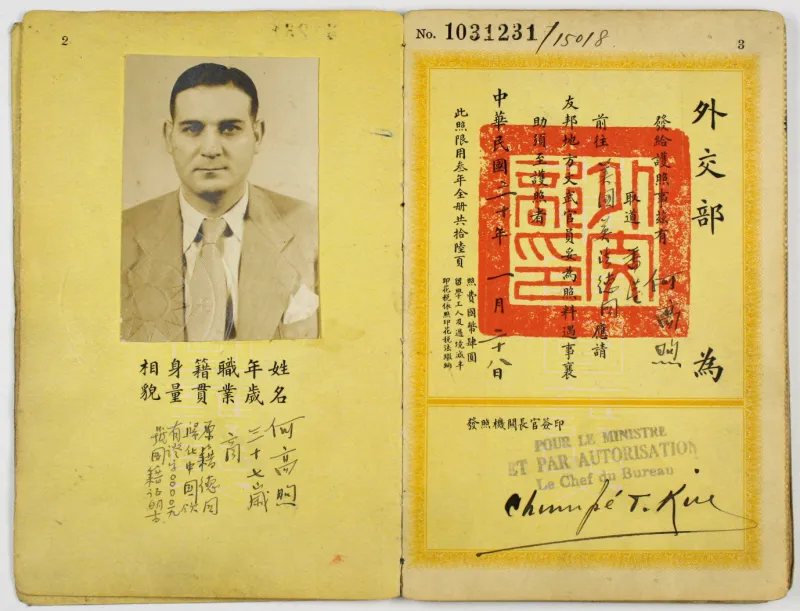

Because of the language and cultural barriers, most Jewish refugees did not have close contact with the local Chinese communities and remained culturally independent. However, in my research I found two interesting objects that show not only cultural influences but how Jewish refugees and Chinese people became part of the same families: a wedding card with a Chinese name “Nee Cheng” and a Chinese passport with a photo of a European-looking face.

I found out that the Chinese woman Miss Nee Cheng was deaf and married to the Ghetto resident David Ludwig Bloch, also deaf, who had miraculously escaped the Dachau Concentration Camp in November 1938. Both Mr. and Mrs. Bloch were art lovers and the wedding card was supposedly designed by Mr. Bloch.

X

X

Chinese passport of Robert Goldschmidt (1904–1980), 1941–1953; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Liliane Ransom

The Jewish man on the Chinese passport is Robert Goldschmidt who was adopted by a Chinese man called Ho Hsien-Li on May 20, 1940 and became the naturalized Chinese Citizen He Gaoxu/Ho Robert Goldschmidt. He received his Chinese passport in war-time Chinese capital Chongqing in January 1941 and later managed to bring some of his family members to China.

All the stories behind these artifacts are Jewish stories, but they are also Chinese stories, even though they are not yet known to Chinese readers. Now I feel I have a new project before me – to tell the stories, in greater detail, to my countrymen. Hopefully they will also be touched, like I have been.

X

X

Robert Goldschmidt (1904–1980) and his Chinese adoptive father Ho Hsien-Li (who died in 1944), ca. 1940–44; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2009/295/44, gift of Liliane Ransom, photo: Jens Ziehe

Wei Zhang, Intern at the Collection, was inspired and touched to see how people from different races, backgrounds, and cultures could become one family out of passion and love for life.

Citation recommendation:

Wei Zhang (2017), When a Certificate Was Not Only a Piece of Paper. How Jewish Memory Objects Preserve Chinese History.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/10673