Making the invisible visible

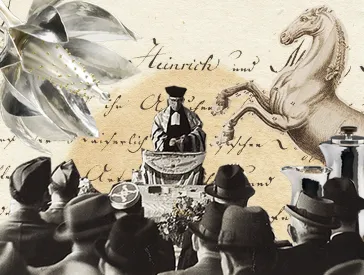

Samson II by Ernest Neuschul, 1923–1955, purchase in 2017

Ernest Neuschul, Samson II, 1924, oil on canvas, 100,5 x 138,5 x 2 cm; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2017/304/0, Misha und Khalil Norland, photo: Roman März. Further information about this photo can be found in our online collections (in German).

The artist Ernest Neuschul was born in 1895 in Aussig in what is today the Czech Republic. He was one of the best-known painters of the New Objectivity movement in the Weimar Republic. However, after fleeing to the United Kingdom, he was largely forgotten in Germany. The work Samson II, which he began in 1923, is a Gesamtkunstwerk of sorts, consisting of a painting and a carved ornamental frame. By the standards of the day, it was monumental in size, measuring 120 by 155 cm.

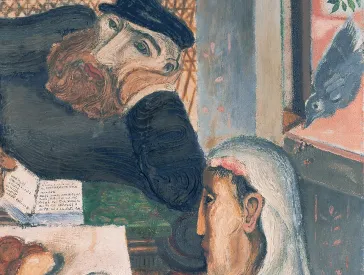

Neuschul applied oil paint in varying thicknesses to a canvas with an irregular coarse weave. In some places there are multiple layers of paint, in others, a layer of paint so thin that the thread structure of the canvas is visible underneath. The painting depicts the scene in which Samson destroys the Philistines’ temple after his hair has grown in and he has regained his superhuman strength.

A painting with unusual layers of paint

When Samson II was purchased for the museum’s collection, we conservators noticed several peculiarities about the layers of paint during our initial examination. While in most places the paint had been gradually mixed on the canvas in order to create smooth color transitions, in others we found very thick layers of unmixed paint that suggested subsequent overpainting.

In order to examine these anomalies without touching the canvas, we exposed the painting to invisible radiation in the ultraviolet, infrared, and X-ray ranges. When comparing the resulting images with the original work, we discovered not only that the artist had reworked the painting several times, but also that the current painting covers a previous version titled Samson I. A black-and-white photo of this version can be found in the artist’s photo album.

Searching for clues

The examination with ultraviolet light revealed a typical natural resin coating in whose greenish fluorescence many dark blotchy patches were visible. Here the artist applied oils over the original layer of paint using stippled brush strokes that still can be seen in places.

The jagged white lines in the sky have a striking pink glow, which suggests that he applied a white lead paint over the varnish here.

The ultraviolet light revealed areas of dark paint over the varnish; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Christoph Schmidt, Gemäldegalerie Berlin.

Ultraviolet Examination

Examining a painting with ultraviolet light allows conservators to identify natural resin varnishes and different types of pigments by their characteristic fluorescence. This is the typical glow that materials give off after being exposed to ultraviolet radiation.

The artist made preliminary charcoal drawings on the primer coat of his paintings.1 With the help of infrared light, we were able to detect a few lines from one drawing in an area with a very thin layer of paint.

We were also surprised to find several signatures by the artist under the currently visible layer of paint. For example, the initials “EN” can be seen in the area with the charcoal drawing, and two additional signatures, in the lower right corner. One of these signatures is also visible in the photo of the preliminary painting Samson I.

Infrared light revealed lines of the preliminary charcoal drawing; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Christoph Schmidt, Gemäldegalerie Berlin

Infrared Examination

When infrared light is used to examine a painting, its rays penetrate the uppermost layers of paint and are reflected by the base. This allows conservators to make visible what is underneath the surface.

With the help of X-rays, we discovered yet another signature in the lower middle section of the painting. Here Neuschul applied a layer of white lead paint over an existing layer of paint and scratched his name in it with the handle of his brush. Due to the displacement of the lead paint, the signature is clearly visible in the X-ray.

X-ray Image

When paintings are exposed to X-ray radiation, the X-rays penetrate the work and are recorded on a film behind it. They show not only metal components such as nails, but also layers of lead pigment paint, which block the X-rays and appear white in the images.

Long creation process

Thanks to these examinations, we now know that Ernest Neuschul initially painted Samson I over a charcoal drawing. The painting bears the signature “Ernest Neuschul / Sept. 1923” in the lower right corner and is mentioned in an exhibition review published by Max Brod in the Prager Abendblatt2 on January 17, 1924.

In the following decades, overshadowed by war and flight, Neuschul made several changes to the painting. He modified the composition of the mountains on the right, painted over details of the columns and the chain on Samson’s foot, altered the signatures, and created a more dramatic sky. Although it is impossible to precisely date these painted-over sections with radiation technology, we learned from captions in the artist’s photo album that the changes were made in the period up to 1955. The Samson theme appears to have preoccupied Neuschul for more than 30 years. Another photo in his album features a painting now considered lost: Samson III.

Franziska Lipp, paintings conservator

Citation recommendation:

Franziska Lipp (2021), Making the invisible visible. Samson II by Ernest Neuschul, 1923–1955, purchase in 2017.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/8433