Androgynous Characters in Isaac Bashevis Singer's Literary Shtetl

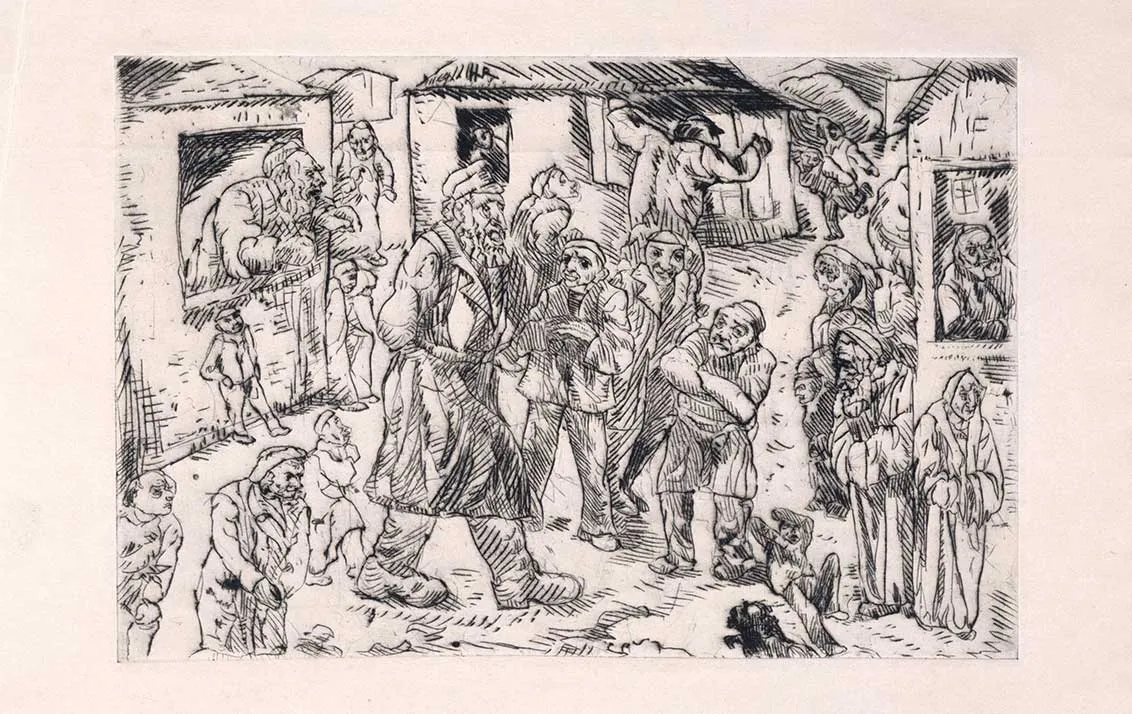

Abraham Palukst (1895–1926), Call to Sabbath Prayer, 1923, Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe. More information on this object can be found in our online collections (in German)

“[Singer’s] Jews are adulterers, divorcées, prostitutes, homosexuals, atheists, converts, thieves, idlers, gluttons [...], saints and sages, merchants and laborers, householders and housewives. They are, in other words, human beings.”

William Desiewicz used these words to describe the characters that populate the literary shtetl of Jewish author Isaac Bashevis Singer (1904–1991). Singer himself was originally from the shtetl. While it was mainly in the United States, where he later moved, that he was active as an author, the shtetl remained the central setting of his stories, and he wrote in Yiddish.

“Adulterers” and “homosexuals”, as well as cross-dressers and queers - characters who break up the gender roles of the shtetl - abound in Singer’s short stories.

What is a shtetl?

Shtetl (Yiddish for little town), before the Second World War, villages, towns or districts with a predominantly Jewish population; everyday language in the shtetlach: Yiddish

What is androgynous ?

Collective term for people who cannot be assigned to the binary categories of “male” or “female”; there are more than two gender categories in the rabbinic literature

Androgyny and Binaries in the Fundamental Texts

How are androgyny and gender roles handled in Judaism more generally? To answer this, it is helpful to take a look at the fundamental texts. In feminist theology, it is now common to analyze the Tanakh through questions specifically about androgyny, gender roles and homosexuality. An example of this is reading the first human, Adam, as an androgynous being in the creation story. This interpretation is not new – it can be found, for example, in the “Wayiḳra Rabbah” Midrash 12:2 – but has now been imbued with modern concepts (e.g. non-binarity).

What is the Tanakh?

Tanakh (Hebrew for the Hebrew Bible), collection of holy scriptures of Judaism; the Torah is part of it

Such sections of the Tanakh and their rabbinic interpretations raise questions about the extent to which the image of gender embedded there is actually binary. Nevertheless, considering the gender-specific purity laws and the clear division of labor in the family construct, it cannot be denied that a clear binary separation between the sexes predominates. The following verse, Deuteronomy 22:5, is an example of this distinction and especially relevant to the topic of androgynous characters: “The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman’s garment: for all that do so are abomination unto the Lord thy God.”

Androgynous characters and people are not foreign to rabbinic literature, where there are clearly more than two gender categories, including, for example, the androgynos and the tumtum. However, there is no agreement among researchers as to whether these should be classified as absolute exceptions within the binary system, or whether they really amount to a “third gender”. Either way, it is important to remember that modern, Western concepts, like intersexuality and transgender, are related to modern, Western constructions of gender, and, as such, are not easily transferable.

Tumtum by Gil Yefman in the glass courtyard of the Jewish Museum Berlin; Courtesy of the artist, photo: Jens Ziehe, production made possible by THE FRIENDS OF THE JMB, supported by Asylum Arts at The Neighborhood and Artis – www.artis.art

What about in Singer?

In the historical shtetl, women and men were clearly bound to binary gender roles, which were primarily derived from religious texts and their interpretation. Historical sources that deal with the violation of these gender roles and the negotiation of an “in-between” are rare.

At least five of the short stories set in Singer’s literary shtetl feature androgynous characters. Many people are probably familiar with Yentl from Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy (1963), who assumes the role of the Yeshiva student Anshel so she can study Torah. In doing so, she mainly uses her external appearance to conceal her identity. When she falls in love with another Yeshiva student and later – in her role as a man – marries a woman, all lines are suddenly blurred: both between genders and between queerness and heterosexuality. This makes the story of Yentl a good example of how androgynous characters are often used in Singer’s stories to explore the theme of homosexuality. By having the androgynous character switch between genders, heteronormative societal rules are experimented with and put to the test.

Pinchosl from Disguised (1986) and Zissel/Zissa from Two (1976) are less well known. Both grow up as boys, marry a woman unwillingly, and finally flee both the marriage and the shtetl to live in a larger city – with a man and in the role of a woman. Pinchosl’s story is told from the perspective of the wife he leaves behind, while Zissel/Zissa is the protagonist of the story. Both characters maintain their faith, or at least their practice of faith, even though they are clearly guilty of sin in the eyes of the narrator and other characters because of their “cross-dressing”.

The short story Androygenus (1975) is a reflection on theological questions told from the perspective of a Rabbi, including reflexions through the physically and behaviorally androgynous character Shevach. For the first time, a figure is depicted who is clearly also biologically “in-between”, and only here is the androgyny not really a subject of the story, but rather serves as a metaphor for dealing with theological questions.

Isaac Bashevis Singer (1904–1991). From the Aufbau image archive; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of the Aufbau collection New York (1934–2004)

Faith and Modernity

In the eyes of the narrators, the actions of Singer’s androgynous characters are judged to be at least questionable from a religious and moral perspective, but they are not denied their Jewish faith. One thing almost all of them have in common is that, despite being aware (or believing themselves to be aware) of “sinning” in their liminal gender expression, they still retain their faith. The clearest example of this is Yentl, for whom nothing is more important than learning the Torah – even if to do so she must, according to some interpretations, break with religious precepts. Here, it must be asked whether any character in Singer is ever represented as actually being morally or religiously flawless, since both his realist narratives and his more supernatural texts depict people in all their subtleties, well beyond simplistic moral classifications. Instead, his characters become the focal points of his intensive, complex interrogation of faith and modernity.

It becomes clear that the self-appraisal of their own androgyny as religiously and morally questionable improves the standing of the androgynous character in Singer’s shtetl. His stories of characters with this self-appraisal, who even show something like remorse, have happier endings. In addition, there are clear differences in the moral evaluation of homosexuality depending on whether or not it happens within the framework of an imitation of heteronormative binary structures or not. Zeitl and Rickel, for example, are judged more harshly than Pinchosl, whose marriage maintains the appearance of heterosexuality.

In Singer’s short stories, clothing and marriage are, among other things, central to the breaking of gender binaries. Cross-dressing becomes an effective tool of fluid transformation between the genders, and marriage represents the basis of the binary gender framework in which the characters operate. Within heteronormative marriage, sexuality becomes a topic that can be spoken about; homosexuality, on the other hand, is only treated in relation to same-sex love and infatuation, not really in terms of homosexual desire and homosexual intercourse.

Ultimately, none of the characters discussed here are really granted an unconditional, true happy ending. Their stories end at best with a life of concealment or heartache, and at worst in an unmarked grave. Does this perhaps make the themes of androgyny and homosexuality easier to digest for a conservative readership? Is Singer leading them to a “just”, punitive fate? Or is he merely depicting a reality? To explore these questions, I would like to delve even deeper into Singer’s work in the future – and everyone is highly recommended to take a look at the stories for themselves.

Helena Lutz is studying Jewish and Cultural Studies at the University of Potsdam. Since 2023, she has been a student assistant in the Digital & Publishing team at the Jewish Museum Berlin. This essay is an abbreviated version of her Bachelor’s thesis, Yentl, Anshel, Zissa: Androgyne Figuren in den Kurzgeschichten Isaac Bashevis Singers (Eng: Yentl, Anshel, Zissa: Adrogynous Characters in the Short Stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer; forthcoming at medaon.de).

Sex: Jewish Positions: Features & Programme

Exhibition Webpage

Sex: Jewish Positions: Exhibition, 17 May to 6 Oct 2024

Publications

- Sex. Jüdische Positionen: Catalog accompanying the exhibition, German edition, 2024

- Sex: Jewish Positions: Catalog accompanying the exhibition, English edition, 2024

Digital Content

- Letʼs Talk About Sex: Online feature accompanying the exhibition

- What do the artists say? Interview series accompanying the exhibition

- Listen to the exhibition’s soundtrack: Playlist on Spotify

- The Song of Songs. Between Literal and Allegorical Loves: Essay by Ilana Pardes

- “Sex Is A Force:” Interview with Talli Rosenbaum

- Current page: Androgynous Characters in I.B. Singer’s Literary Shtetl: Essay by Helena Lutz

- Jewish Places: Find information about Jewish sites related to the exhibition on our interactive map

Citation recommendation:

Helena Lutz (2024), Androgynous Characters in Isaac Bashevis Singer's Literary Shtetl.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/10441