LGBTQI+

An Anecdotal Glossary

At first glance, LGBTQI+ seems to be a useful abbreviation that brings together various sexual orientations, gender identities, and walks of life under one umbrella. (In German, the I usually appears before the Q.) Upon closer inspection, however, it becomes clear that the abbreviation itself actually needs its own glossary.

L

L – as in lesbian

And in Judaism?

Same-gender relationships are a complex subject in Judaism. Despite stereotypes, not all Orthodox Jewish communities reject homosexuality and homosexual people. In the United States, there is a rich subculture of queer (more on this adjective under Q) traditionalists, Orthodox queer people, Modern Orthodox queer rights activists, and queer Orthodox congregations. Nevertheless, the rough rule of thumb is that Reform Judaism is more open-minded than Orthodox Judaism, and lesbianness is considered less of a violation of Jewish law than gayness.

Still, the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) includes one of history’s most beautiful lesbian love stories, that of Ruth and Naomi. Although this text – including the declarations of love between the two women – is traditionally read as a symbol of solidarity among women, in the practice of re-reading or queer reading, it is seen as an example of lesbian representation in Jewish scripture.

Ruth and Naomi in the bible illustration by Paul Gustave Doré, 1899; in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“For wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die, and there I will be buried.”

Those were the words of Ruth, a young Moabite, to Naomi, a significantly older Ephratite.

G

G – as in gay

And in Judaism?

In many Orthodox communities, relationships and sex between men are considered to be a violation against the commandment to be fruitful and multiply. The story of Sodom is used as evidence that G-d is against relationships and especially sex between men. Yet upon reading the story, it is clear that the focus of divine retribution is not on sexuality, but on sexualized violence. The narrative does not portray any consensual relationship between two men that G-d would punish. Rather, this is an act of pure violence in which feverish Sodomites attempt to gain sexual access to three angels against their will. The result of this attempted assault is the downfall of two cities. Predominantly Reform, feminist, and queer interpretations therefore read the story of Sodom and Gomorrah as a clear condemnation of sexualized violence, not as a warning against homosexuality. From a queer reading, the story of David and Jonathan in the Book of Samuel attests to gay love in the Tanakh.

B

The B is a bit trickier: B for bi or bisexual

What might sound like slight nuanced differences in fact conceal political debates around the question of self-positioning and the dimensions between sexuality and desire, romance, relationships and physicality, passion, and lived realities.

And in Judaism?

David and Jonathan, drawn by Gottfried Bernhard Göz (1708–1774); in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As in the debates over desire in general, bisexuality is often overlooked or neglected in examinations of sexuality and Judaism, even though bi people face the same obstacles in regard to same-gender relationships and same-gender sex as gay men and lesbians. However, there is a small distinction if they are currently in a relationship perceived as heterosexual. In 2016, Beit Hillel – an organization of well-known Orthodox rabbis in Israel – published a paper asserting that according to halakhah, the reprehensible sin is not (same-gender) desire itself, but only acting upon it. This does not make the Orthodox council’s stance towards gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals less problematic per se, but for many it was still a revolutionary step in the right direction by these Orthodox communities.

T

The letter T represents entire political movements struggling for recognition, with the term transgender having progressively replaced the older word transsexual in English usage. Today, to do justice to the dimensions of these debates and the different lived realities behind them, the shorter form trans (often written trans*, with an asterisk, in German) is often used, and in some cases the T is written twice. It is important to note that trans and transgender, like the words gay, bi, and queer, are only used as adjectives in English. (Lesbian and bisexual can also be used as nouns.) So when referring to people with these identities, you can say lesbians, gay men, bisexuals (or bi people), trans people, and queer people, but not “gays,” or “transgenders.” Because of its complicated history as a reclaimed slur, it is also best to use the word "queer" as an adjective, although some of the queer community proudly use it as a noun amongst themselves."

And in Judaism?

In this regard, Judaism certainly has a leg up on Christianity. Unlike the Christian tradition, Judaism recognizes six genders rather than two. And two of them, from a modern interpretation, describe the lived realities of trans people – even if the spectrum remains very binary, addressing only transitions from female to male (Ay’lonit/איילונית) and male to female (Saris/סריס).1 The descriptions of these genders are largely biologistic, but they also incorporate aspects of habitus, perception, and self-definition. But most importantly, the acknowledgement of these genders inescapably recognizes trans peoples’ right to exist. Judaism recognizes that gender is mutable and changeable and creates space for it outside cis-masculinity and cis-femininity.

I

The letter I has gone through a similar discursive change – especially in the German-speaking world. Traditionally, it stands for “intersex people,” and to this day there are people in Germany who identify by the direct German equivalents Intersexuelle or intersexuelle Personen. However, because the German word “sex” does not also connote gender, and based on the argument that this is not a sexuality, the more common and apt term in German today is intergeschlechtlich, which is closer to “intergender.” Again, the practice of using an asterisk in German – inter* people – is an effort to do justice to the spectrum of debates and lived realities by encompassing both the terms intersexuell and intergeschlechtlich.

And in Judaism?

One interpretation of the origin story in Genesis 2 (best known as the story of Adam and Eve), which is not so unusual in the canon of Jewish knowledge, is that the world’s first human was an inter* person. Two more of the six total genders in Judaism are androgynos (אַנְדְּרוֹגִינוֹ) and tumtum (טֻומְטוּם). Both of them characterize people whose bodies correspond to a unique gender. The contemporary social discourse says there are men, women, and people who deviate from the two. Today, inter* people still struggle to be recognized as a separate gender in their own right. Although Judaism also asserts differences from men and women, it does not define tumtum and androgynos as merely a deviation or malformation thereof, but rather treats them as separate, valid genders. And that’s not all. If we follow the premise that the first human (by the way, adam is not a man’s name, but the Hebrew word for “human”) was androgynos, humanity’s origins began in the hands of an inter* person.

Q

Q – for queer. This term, first coined in US English, has no easy German-language equivalent. Originally used as a slur, it was reclaimed by activists in the 1980s and 1990s as a self-designation. The concept eventually arrived in Germany, where there are very diverse substantive ideas about its meaning and definition. First, it was primarily used politically and in regard to various dimensions of discrimination. Today, the word “queer” is often used as a catch-all for people who diverge from society’s preconceptions about gender, desire, sexuality, and relationships.

And in Judaism?

If we trace queerness back to the political movement of calling existing structures into question and reevaluating systems in keeping with the times, queerness and Judaism are actually soul sisters. Questioning lies at the foundation of Jewish thinking, and these questions must be asked afresh over and over. This goes hand in hand with the knowledge that there are no clear answers, and certainly no simple ones. We reread the Torah every year from the start in the knowledge that what we read changes because we change: the context of our reading changes, and what we need to get out of the text changes. Judaism has a long tradition of transformations and changeability. Queerness places faith in changeability and is, itself, the transformation to structural change.

Ruth. Plate 6 from the file: Ruth by Fritz Lederer (1878–1949); Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

+/*

The plus sign or asterisk represents the idea that a list of lived realities always leaves out many unseen ones. It symbolizes the knowledge that the list is never complete and never a perfect fit: that gender and desire are too complex to be able to be summed up in a row of letters, and that it is in fact debatable whether gender and desire should share the same list at all.

And in Judaism?

Over the past few years, within Jewish communities in Germany, there has been a growing consciousness of the need to pay attention to the gaps. Since the 1980s, groups, activists, initiatives, and associations in Germany have been pointing out that Jewish places must also be places for Jewish LGBTQI+ people. Conversely, ample awareness-raising efforts have been made to ensure that LGBTQI+ communities can be homes for LGBTQI+ Jews. In fact, Judaism has a long tradition of creating space for people who otherwise go unheard. For this reason, in Jewish jurisprudence, a verdict is considered invalid if it is reached by consensus. This is because if everyone is unanimous with no contradictions, other perspectives must be missing. The judges sit in a circle, but for this very reason, that circle is never closed. Only if the permanent presence of vacancies is known and space is set aside for them can other people step in and hopefully fill those vacancies.

The symbol of the vacancy is not an admission of failure, but a space in which knowledge can grow and in which neglected considerations are invited into the canon. The circle broadens, but the gap is never closed because there is always a need to reserve space for the unknown, for the forgotten, for people still finding their voices, and for people who simply have not been listened to yet. The symbolic asterisk or plus sign in the historical practice. Theoretically speaking...

Debora Antmann is a columnist and political educator working at the intersection between Judaism, feminism, and queer studies. She has published about the history of the Jewish feminist movement in variety of media. By now, not only is she a member of the Jewish Museum Berlin’s Digital & Publishing team, but she can even be seen in the permanent exhibition on one of the 21 screens of the Mesubin installation.

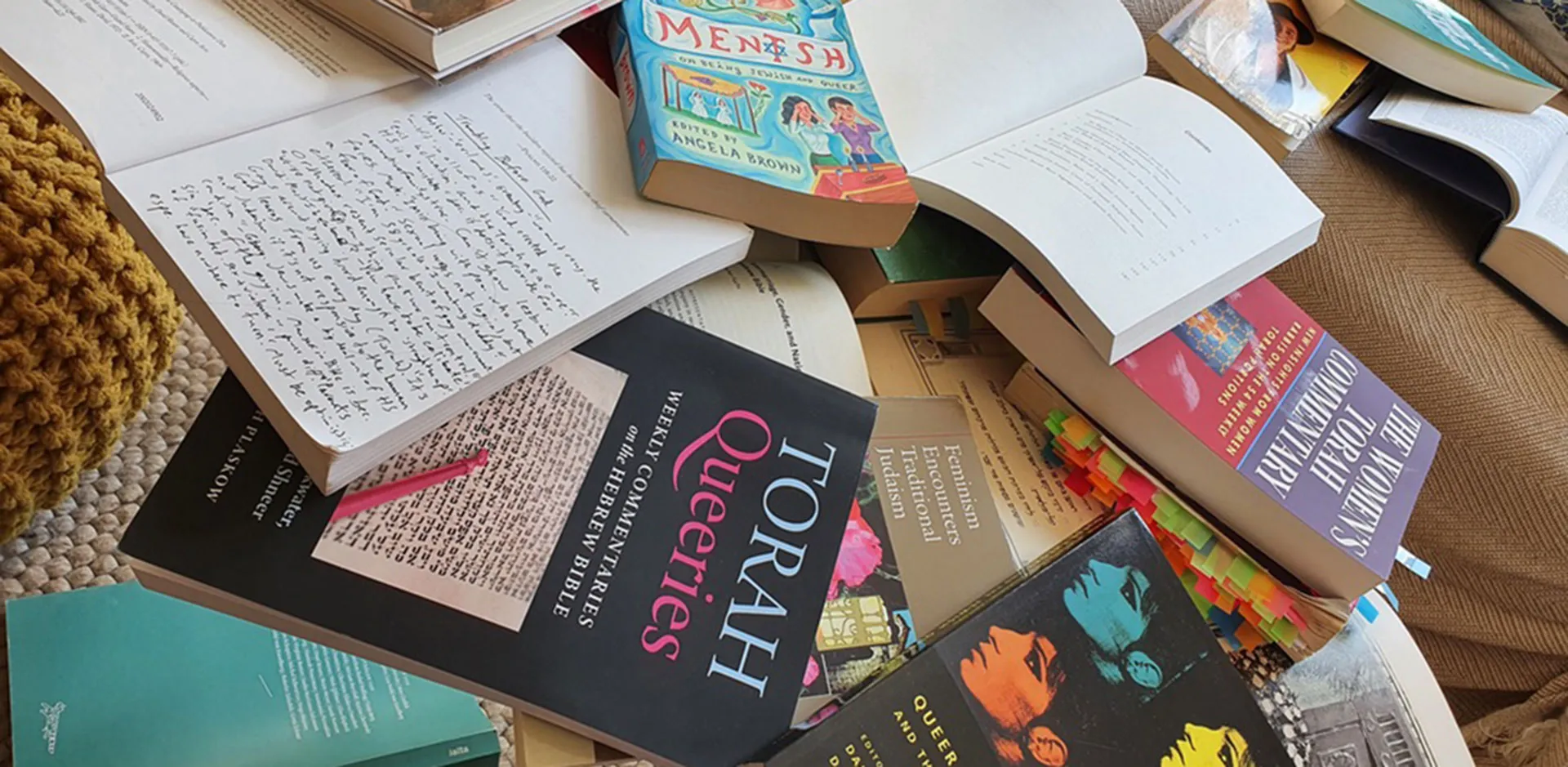

Most queer Jewish specialist literature, such as Torah Queeries, Becoming Eve, Queer Theory and the Jewish Question or Mentsh, is in English and is certainly worth reading; photo: Debora Antmann

- The adjectives in italics are “assigned” genders, that is, the gender assigned to a person at birth, which does not match the gender a person identifies as. ↩︎

Citation recommendation:

Debora Antmann (2021), LGBTQI+. An Anecdotal Glossary.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/en/node/7645