Shoah (1985) by Claude Lanzmann

The French intellectual and filmmaker Claude Lanzmann (1925–2018) dedicated nearly twelve years of his life to researching, filming and editing Shoah. With a runtime of 566 minutes, this epic work remains a unique cinematic testament to the systematic murder of European Jewry, and has become a central reference point in the examination of the Nazi regime’s mass crimes.

Incentive and Research

In 1973, Alouf Hareven, an official in the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, approached Lanzmann with a bold request: to make a film “that is the Shoah.”

Lanzmann had just completed his first documentary film, Pourquoi Israël (Israel, Why). When after much hesitation he finally said yes, he already had an idea of the possible magnitude of this project. The result was Shoah, the film that would define Lanzmann’s career and shape the rest of his work.

The undertaking began with a period of intensive research. The meticulous scholarship of historian Raul Hilberg was especially valuable to Lanzmann, and Hilberg would later appear as one of the film’s protagonists. Together with Corinna Coulmas and Irena Steinfeldt, Lanzmann searched archives in countries such as the USA and Germany for sources and names – not only of survivors, but also of perpetrators. For Lanzmann, the film had to include the voices of both victims and perpetrators. Alongside victims and perpetrators, he also sought testimony from representatives of Allied governments and Jewish organizations.

Preliminary Interviews and Audio Recordings

Lanzmann then began conducting preliminary interviews with possible protagonists. Where necessary, Coulmas and Steinfeldt served as interpreters and also conducted interviews themselves across the globe. Guided by his keen intuition and grounded in thorough research, Lanzmann interviewed eyewitnesses on every aspect of the persecution and extermination of European Jewry.

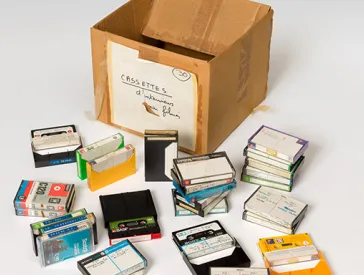

These early interviews were recorded on audio cassette tapes. When speaking with Nazi perpetrators – mostly men, though one woman was among them – the recording device was usually hidden in a bag. More than 220 hours of these audio recordings from the Shoah research phase still exist and have been part of the collection of the Jewish Museum Berlin (JMB) since 2021.

Audio cassette tape documenting the preliminary interview with Mary Sirkin; Jewish Museum Berlin, accession 2021/153/94, gift of the Association Claude et Felix Lanzman

Footage and Outtakes

In the summer of 1978, Lanzmann began systematically shooting the film. The first footage was recorded in Poland at former German death camps, followed by filming in many other countries in this and the following year. To film the interviews with perpetrators, the so-called Paluche – a type of hidden camera – was used. At the time, only a few of these cameras existed worldwide.

Some of the research topics had to be set aside before Claude Lanzmann even started filming, while others were abandoned during the years-long editing process. The unused footage – the Shoah outtakes – is now accessible via the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. Along with the audio archive of the Lanzmann Collection at the JMB, these outtakes give an idea of the film’s extensive preliminary research and thematic scope.

Cinematic Language

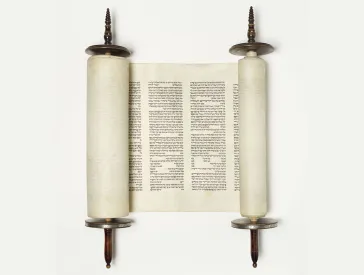

At the center of the film, which premiered in Paris on 30 April 1985, is the mass murder of millions in the extermination camps. Lanzmann describes the survivors he interviews as “revenants

” (those who have returned), who, sometimes at the sites of the extermination itself, sometimes in distant exile, bear witness not only for themselves but for all those who died. He also speaks with other direct witnesses to the extermination: Christian Polish residents who lived with nothing but a fence between them and the camps. Finally, he interviews Nazi perpetrators, who recount their crimes to a hidden camera. The film includes many shots of railway tracks and a locomotive like the one used to deport millions of people to the death camps, along with images of the remnants of the killing sites and the landscapes that surround them.

Film Stills from Claude Lanzmann’s Film Shoah

Lanzmann chose not to use historical footage of corpses or the camps. Instead, he focuses on what remains – the vanishing traces, the emptiness, and the struggle to express the inexpressible. Through his cinematic language and the portrayal of personal testimony and historical landscapes, Lanzmann connects the past to the present. He never saw Shoah as a documentary. Rather, it was an attempt to make the invisible visible.

Reception

Shoah was first screened in Germany in 1986 at the Berlinale, followed by broadcasts on the WDR and NDR networks. The film’s reception was divided. Political circles and parts of the public felt that it threatened West Germany’s self-image. The Bavarian Broadcasting network campaigned successfully to prevent Shoah from being aired on ARD. Reviews in newspapers, magazines and journals, however, were mostly favorable, and the film and its director were awarded numerous prizes on the international stage.

Film Posters

To this day, Shoah is considered a groundbreaking cinematic exploration of the Nazis’ mass crimes against European Jewry. In 2023, both Shoah and the Lanzmann audio archive were added to the UNESCO Memory of the World register.