Defiance

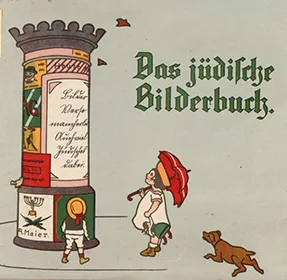

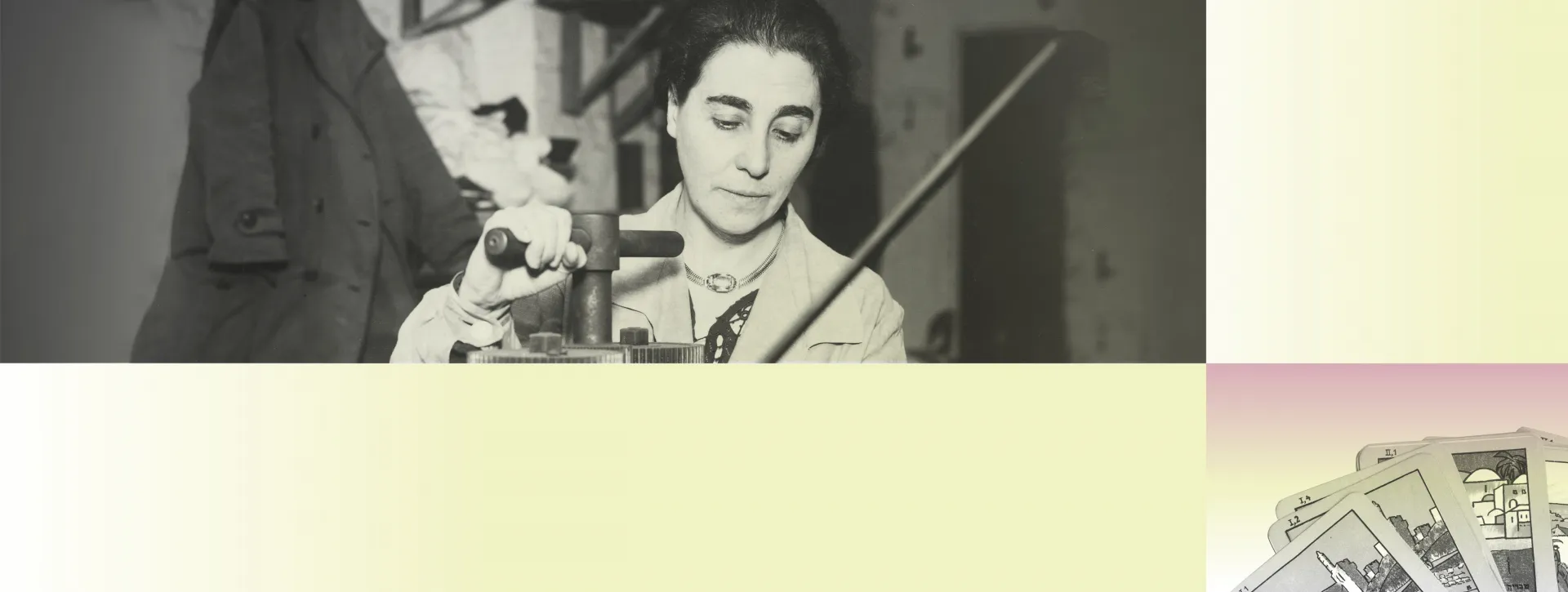

Jewish Women and Design in the Modern Era: exhibition

“German women wanted to show what a cultural force they had become, what they were achieving in all fields, sometimes in a completely new, independently creative way. An unforgettable image. […] We Jewish women could also walk through this exhibition filled with modest pride. Our work was in no way inferior to that of our sisters of other faiths.”

This is how Ella Seligmann described the opening of The Exhibition of Women at Home and at Work in Berlin in February 1912. One year later, in 1933, the National Socialist regime began to systematically destroy the careers and lives of many of these women.

The exhibition at the Jewish Museum Berlin is the first to honor the work of German-Jewish craftswomen who, during a time marked by exclusion and upheaval, forged their own paths. It presents the lives and works of more than 60 Jewish female designers and demonstrates how they overcame societal barriers to fight for change and visibility — and how they paved the way for other women in the process.

Past exhibition

Where

Old Building, level 1

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

Defiance: Jewish Women and Design in the Modern Era

Exhibition Webpage

Current page: Defiance: Jewish Women and Design in the Modern Era (11 Jul to 23 Nov 2025): visual and audio resources relating to the exhibition and information in German Sign Language

Publications

Exhibition catalog: 2025, in German

Digital Content

- Jewish Women and Design in the Modern Era: All biographies at a glance

- Jewish Places: Important places where the Jewish designers lived and worked on our interactive map

- Do you know Eva Samuel?: How the research for the exhibition took off

- Small Puppets – Strong Women: community project accompanying the exhibition (in German)

- Objects from the exhibition in our collection online in German

See also

- Paper doll based on a costume design by Dodo (1907–1998): Create your own movable paper doll!

- Beaded bracelet based on a design by Emma Trietsch (1876–1933): Make your own beaded bracelet!

- Fashion paper doll based on designs by Irene Saltern (1911–2005): Dress your own fashion paper doll!

- Jewish Women Ceramists from Germany after 1933: Online feature on Google Arts & Culture, in German

Sneek Peak into the Exhibition

Information on the accessability of the exhibition

- All exhibition texts are available in German and English.

- There is no information in Plain Language.

- There is no information in British Sign Language (BSL) or International Sign Language (ISL).

- The opening evening will be translated into German Sign Language (GSL).

- There is no hearing amplification in the form of induction systems and neck ring loops.

- The exhibition is accessible.

- Objects and texts are mostly legible from a seated position.

- There are places to sit and rest at various points in the exhibition#.

- Wheelchairs can be borrowed free of charge from the checkroom. You can reserve the wheelchairs in advance by sending an e-mail to besucherservice@jmberlin.de.

- The works of art in the exhibition are not uniformly brightly lit.

- The exhibition texts are predominantly visually rich in contrast.

- There is neither a floor guidance system, nor tactile models in the exhibition.

- There are neither flashing lights, nor loud sound in the exhibition spaces.

- All film stations in the exhibition are silent. All films have German and English subtitles.

You can find up-to-date information on the museum’s accessibility and facilities on our website.

Do you have any further questions or comments on accessibility? Then please write to us using our contact form.

Exhibition Information at a Glance

- When 11 Jul to 23 Nov 2025

- Where Old Building, level 1

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin

See Location on Map

Credits

Director

Hetty Berg

Management

Lars Bahners (Verwaltung), Julia Friedrich (Sammlung), Barbara Thiele (Vermittlung und Digitales)

Executive Assistants and Aides

Milena Fernando, Mathias Groß, Vera von Lehsten, Eva Weinreich

Curator

Michal S. Friedlander

Curatorial Advisor

Martina Lüdicke

Exhibition Manager

Deniz Roth

Project Assistant

Julia Dellith

Student Assistant

Laura Schummers

Voluntary Service

Finn Ferschke, Luise Orth

Head of Exhibitions

Nina Schallenberg

Collection Managemet

Katharina Wippermann (Leitung), Ulrike Gast (Registrar), Iris Blochel-Dittrich, Birgit Maurer-Porat, Valeska Wolfgram (Dokumentation)

Conservators

Barbara Decker, Stephan Lohrengel (paper), Rüdiger Tertel (metal), Ava Hermann, Ines Zimmermann (textile)

Exhibition Design (concept, architectur, graphic design, production management)

Anschlaege.de, Studio for Design

Marketing Campaign

Visual Space Agency, Julia Volkmar

Studio Bens, Jens Ludewig

Exhibition Texts and Copyediting

Michal S. Friedlander (texts), Martina Lüdicke, Marie Naumann, Katharina Wulffius (editing), Henriette Kolb, Anika Reichwald (copyediting)

Translation and Copyediting

Allison Brown (German-English), Michael Ebmeyer, Tanja Klapp (English-German), Kate Sturge (copyediting English)

Graphic design and layout of the craft sheets

Laura Schummers

Exhibition Construction

spreeDesign

Art Handling

Fißler & Kollegen GmbH

Media Planning and Installation

Eidotech

Painter

Lazar Malermeister GmbH

Graphic Production

Atelier Köbbert

Audio Production

Studio Platzhalter

Exhibition Lighting

Victor Kégli

Electrician

Apleona GmbH

Education and Communication

Diana Dressel (Department head), Nina Wilkens

Accompanying Programme

Daniel Wildmann (Department head), Signe Rossbach (Event curator), Maria Röger, Shlomit Tripp, Katja Vathke

Archive

Aubrey Pomerance (Department head), Franziska Bogdanov, Ulrike Neuwirth, Jörg Waßmer

Library

Monika Sommerer (Department head), Bernhard Jensen, Theresa Polley, Ernst Wittmann

Marketing and Communication

Sandra Hollmann (Department head), Katrin Möller, Ha Van Dinh, Margret Karsch, Melanie Franke, Julia Jürgens, Amelie Neumayr

Digital and Publishing

Steffen Jost (Department head), Marie Naumann, Katharina Wulffius (Catalogue), Marina Brafa (Website), Debora Antmann, David Studniberg, Charlotte Struck (Jewish Places), Lea Simon (Research trainee)

Visitor Experience and Research

Christiane Birkert (Department head), Susann Holz, Johannes Rinke

Development

Anja Butzek (Department head), Sarah Winter

FREUNDE DES JMB

Johanna Brandt (management)

Events

Yvonne Niehues (Department head), Juliane Ganzer, Katja Rein, Falk Schneider, Danny Specht-Eichler, Gesa Struve

Legal Department and Tendering

Julia Lietzmann (Department head), Sascha Brejora, Olaf Heinrich, Jonas Nondorf

Finance and Controlling

Grit Schleheider (Department head), Odette Bütow, Rainer Christoffers, Andreas Harm, Denise Kurby, Cindy Niepold, Stefan Rosin, Katja Schwarzer

Human Resources

Brit Linde-Pelz (Department head), Manuela Gümüssoy, Lilith Wendt

Facility Management

Manuela Konzack (Department head), Guido Böttcher, Mirko Dalsch, André Küter, Marcel Kühle, Janine Lehmann, Christian Michaelis, Jan Viegils

ICT

Michael Concepcion (Leitung), Anja Jauert, Kathleen Köhler, Sebastian Nadler

Exhibition Maintenance

Leitwerk Servicing

Janitor Service

FAM

Cleaning

Piepenbrock Reinigung GmbH

Sercurity

Kötter Security SE

Sponsors

With funding provided by the Hauptstadtkulturfonds.

We also thank the David Berg Foundation for their kind support.

Media Cooperations