“Quota Refugees:” Russian-Speaking Immigrants to Germany

Between 1991 and 2005, Jews and people of Jewish descent from the territories of the former Soviet Union were entitled to immigrate to Germany by claiming what was known as “quota refugee” status.

The immigration of Russian-speaking Jews from the former Soviet Union marked a major turning point in the post-1945 history of Jewish life in Germany. In the successor states of the Soviet Union, Jewishness was considered a nationality, not a religion. All Soviet citizens had been prohibited from the exercise of religion. Jewish religious practices were therefore unfamiliar to most Russian-speaking Jews who had been born in the Soviet Union.

Thus, the new immigrants arrived with passports marked “Yevrey” and a Soviet variety of Judiasm. And ever since the 1990s, they have altered and enriched Jewish communities in Germany, which saw major growth as a result but also faced significant challenges.

The relationship between long-established residents and newcomers has not been without tension. For example, in the USSR, the nationality of “Yevrey” was passed down from a father to his children – in contrast to Jewish religious law, which considers Jewishness to be inherited through the maternal line. The children of many immigrant families are so-called “paternal Jews.” This leads to clashes with institutional Jewish communities that abide by religious law.

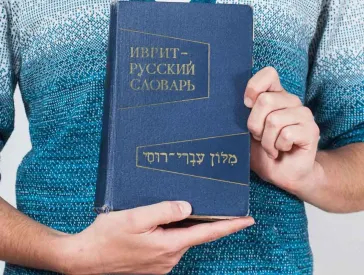

Anatol Benjamin Schapiro brought this very old Hebrew-Russian dictionary to tell his migration story for the Object Days project (learn more); Jewish Museum Berlin; photo: Stephan Pramme.

There are also differences between long-established German Jews and more recent arrivals when it comes to remembrance and commemoration. While 9 November is the most important anniversary for the Jewish community of the former West Germany, Russian-speaking immigrants prefer to commemorate 9 May, the day of Germany’s unconditional surrender and the anniversary of the Red Army’s triumph, which Soviet-Jewish soldiers shared with the entire Soviet Union.

Today, those who arrived in Germany as children or teenagers or were born here are integrated into German society, educated, and politically and culturally active. Especially in literature, younger authors have been particularly prolific. In part, their work offers literary reflections on their own migration stories that underscore the group’s polyphony.

Unlike the ethnic German repatriates from the former Soviet Union, “quota refugees” were not granted German citizenship automatically, but were permitted to apply for it after a certain amount of time had passed. They were eligible for work permits, social security benefits, and “integration assistance” such as a free language course and help with finding housing.

“They call me a ‘hero of the Soviet Union.’” Lev Agranovich, who immigrated to Germany in 1991, has been decorated with twenty-eight honors and medals (learn more); Jewish Museum Berlin; photo: Stephan Pramme.

In this video on the exhibition A is for Jewish, Alina Gromova reports, among other things, on different perspectives on memory and culture among Jews in Germany who are old-established or who have migrated from the former Soviet Union; Jewish Museum Berlin 2020.

When the Immigration Act of 1 January 2005 went into effect, the Quota Refugee Act lapsed. In 2007, the further admittance of Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union was resolved, albeit with stricter requirements than before.

A compasses case, a child's painting, a kosher pan—what do these exhibition objects tell us about the migration experiences of Jews who came to Germany from the former Soviet Union? Theresia Ziehe, a curator of the new core exhibition at the Jewish Museum Berlin, talks about a daughter's longing gaze backwards and a woman's sense of connection to religious tradition in her family; Jewish Museum Berlin 2020. More videos with Our Stories