Glücksmomente einer Fotokuratorin

Ilse Bings Fotografie New York – The Elevated and me

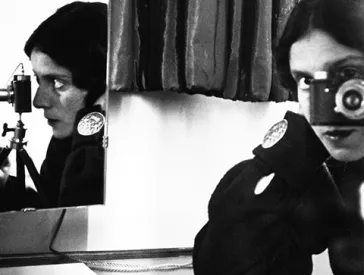

Seit vielen Jahren habe ich ein Selbstporträt der Fotografin Ilse Bing im Blick, das sie 1936 auf ihrer ersten Reise nach New York aufgenommen hat. In den letzten zwanzig Jahren wurde das Bild nur zwei Mal auf dem Markt angeboten: das erste Mal, im Jahr 2009, erzielte ein Vintageabzug in einer Auktion den stolzen Zuschlagspreis von 25.000 Euro.

Aufgrund der Seltenheit und des hohen Verkaufswerts dachte ich damals, dass die bezaubernde Fotografie wohl nie Teil unserer Sammlung werden könne. Sie wurde für mich zum Inbegriff dessen „was ich mir wünschen würde, wenn ich nur könnte….“.

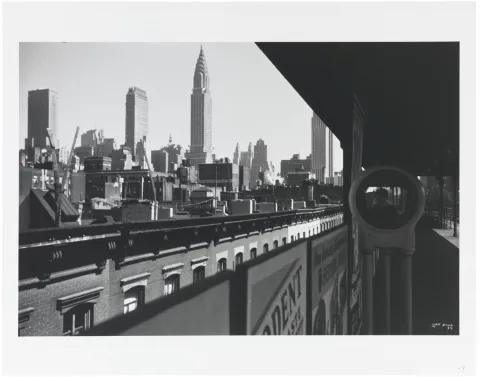

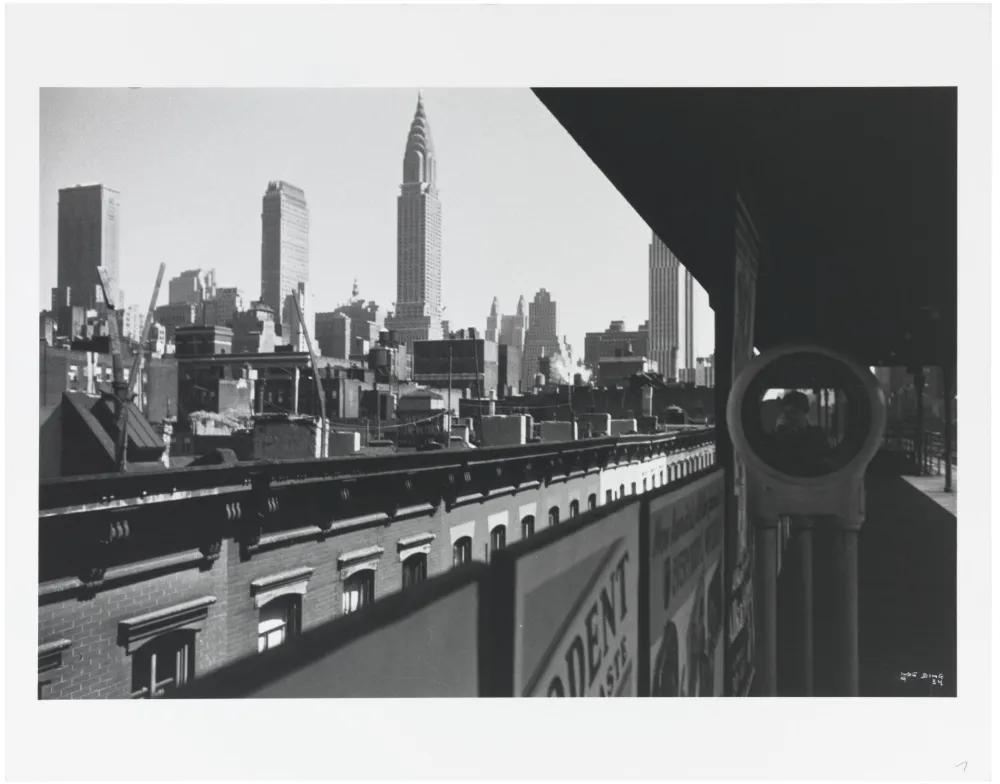

Die Fotografie zeigt eine Station der Hochbahn inmitten der New Yorker Skyline und die Reflektion der Fotografin mit ihrer Leica in einem kleinen runden Spiegel. Der Titel New York – The Elevated and me verweist auf das Wechselspiel zwischen Stadtansicht und Selbstbildnis. Von links kommende strenge Diagonalen bündeln sich im Spiegelbild der Fotografin mit ihrer Kamera. Dabei wirkt die Skyline Manhattans durch die starke Zuspitzung der Linien wie in Bewegung gesetzt. Das Abbild der Fotografin fügt sich in eine komplett menschenleere Umgebung und fragt so nach der Beziehung zwischen Mensch und Stadt. Ilse Bing beobachtet als distanzierte Außenstehende. Zum Zeitpunkt der Aufnahme wusste sie noch nicht, dass sie fünf Jahre später in diese Stadt emigrieren, die amerikanische Staatsbürgerschaft annehmen und bis zu ihrem Tod dort leben würde.

Ilse Bing, New York – The Elevated and me, Abzug (1988) des Originals von 1936; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Inv.-Nr.: 2014/357/0 © Estate of Ilse Bing. Weitere Informationen zu diesem Foto finden Sie in unserer Online-Sammlung

X

X

Ilse Bing, New York – The Elevated and me, Abzug (1988) des Originals von 1936; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Inv.-Nr.: 2014/357/0 © Estate of Ilse Bing. Weitere Informationen zu diesem Foto finden Sie in unserer Online-Sammlung

1899 in Frankfurt am Main geboren, wuchs Ilse Bing in einer bürgerlichen jüdischen Familie auf. Ab 1920 studierte sie Mathematik und Physik, wechselte aber schon bald zur Kunstgeschichte. Da sie für ihre Dissertation Abbildungen benötigte, griff sie selbst zur Kamera. Sie experimentierte mit dem Medium Fotografie und begann 1929 als Fotojournalistin zu arbeiten. Im selben Jahr kaufte sie sich eine Leica, eine damals revolutionäre 35 mm Kamera; Jahre später brachte ihr dies den Namen „Königin der Leica“ ein. Von einer Ausstellung der in Paris lebenden Fotografin Florence Henri war sie so beeindruckt, dass sie sich 1930 entschloss, nach Paris zu ziehen. Im Sommer 1936 reiste sie auf Einladung der June Rhodes Gallery für ihre erste Einzelausstellung nach New York. Ilse Bing war zwar fasziniert von der Stadt, die sich so stark von Paris unterschied, und erhielt verschiedene Auftragsangebote. Diese lehnte sie jedoch ab, um nach Paris zurückzukehren. Hier heiratete sie 1937 den Pianisten Konrad Wolff, einen ebenfalls aus Deutschland stammenden Juden.

Der Einfall deutscher Truppen in Frankreich änderte Ilse Bings Leben schlag artig. 1940 musste sie Paris verlassen und wurde im Internierungslager Gurs festgehalten. Im Juni 1941 gelang ihr zusammen mit ihrem Mann nach einem längeren Aufenthalt in Marseille die Flucht nach Amerika. In New York arbeitete sie weiterhin als Fotografin, konnte jedoch nicht an ihre Pariser Erfolge anknüpfen. Die Zeiten hatten sich verändert: In New York, das immer mehr zur Hauptstadt der fotografischen Medien avancierte, gab es unzählige arbeitsuchende Fotografen.

In den späten 1950er Jahren gab Ilse Bing die Fotografie ganz auf und begann Gedichte zu schreiben, zu zeichnen und Collagen herzustellen. Ihr Werk wurde ab Ende der 1970er Jahre wiederentdeckt, in vielen Ausstellungen präsentiert und fand Eingang in die Sammlungen großer Museen. Bing genoss diese späte Anerkennung; sie starb 1998 in New York. Ilse Bing teilte das Schicksal vieler deutsch-jüdischer Fotografen, deren Lebens- und Emigrationswege über Paris und New York führten. Beiden Städten kommt in der Fotografiegeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts dadurch eine besondere Bedeutung zu. Die Kamera half den emigrierten Fotografen, ihr neues Lebensumfeld zu entdecken und sich in einer fremden Kultur zurechtzufinden. Als anfangs außenstehende Beobachter war ihr Blick nicht selten genauer und kritischer als der ihrer ansässigen Kollegen.

X

X

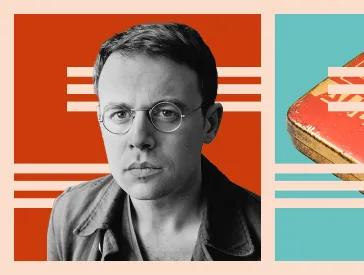

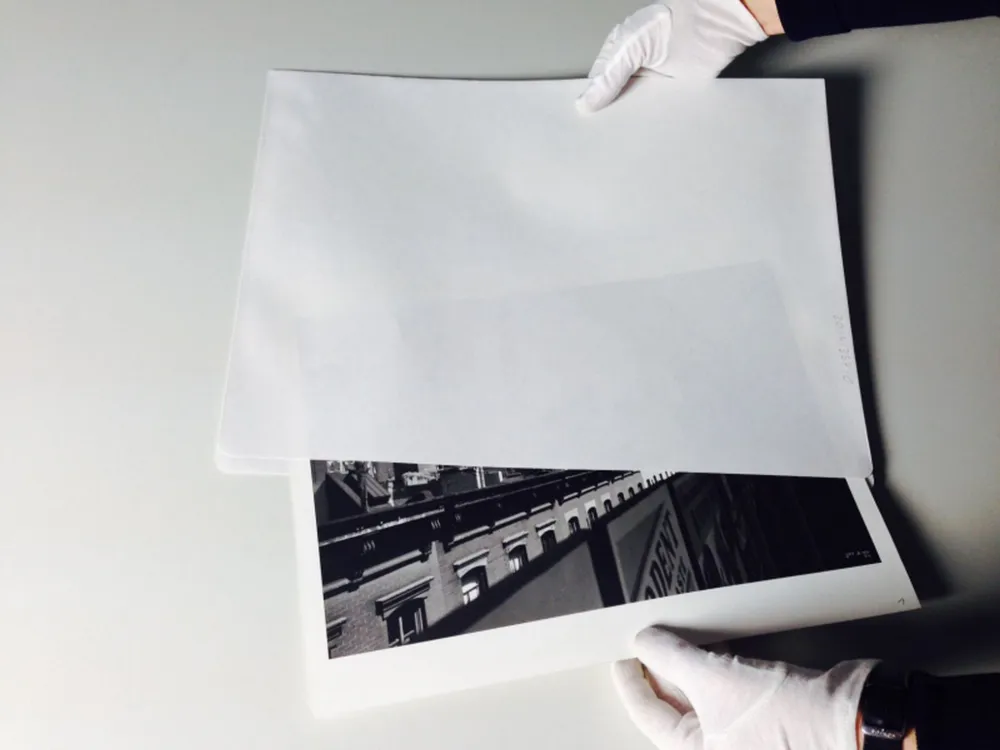

„Endlich in unserer Sammlung“, Theresia Ziehe bei der Begutachtung der Fotografie von Ilse Bing;

Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Foto: Julia Kouzmenko

Die Fotografie New York – The Elevated and me ist Sinnbild für Ilse Bings Emigrationsgeschichte. Sie entwirft ein Wechselverhältnis zwischen Selbstbildnis und städtischer Umgebung und fragt: Wer bin ich? Wer oder was bestimmt meine Identität? Ende 2014 gelang es mir, die lang ersehnte Fotografie zu erwerben.

Für mich war dies ein magischer Moment: Hoffen und Bangen gingen ihm voraus und viele Glücksmomente folgten, als klar wurde, dass die Fotografie, nun um ein vielfaches günstiger als der erste Marktpreis, bald Teil unserer Sammlung sein würde.

Wie jedes Glück, barg auch das meinige einen Wermutstropfen: Unser Neuzugang ist ein Abzug aus dem Jahre 1988. Unten rechts ist der Abzug mit weißer Tusche signiert und datiert, wobei die Autorin die Aufnahme versehentlich auf das Jahr 1934 vordatiert hat. Für eine Fotosammlung in einem kulturhistorischen Museum aber kommt es nicht in erster Linie darauf an, ob es sich um einen Originalabzug aus dem Jahr 1936 oder einen späteren Abzug handelt. Entscheidend bei einer Fotografie sind vielmehr das Motiv und seine Bedeutung.

Ich habe mir lange gewünscht, New York – The Elevated and me in die Fotografische Sammlung aufnehmen zu können. Dass dies nunmehr geglückt ist, wird hoffentlich in Zukunft weitere Menschen beglücken.

Theresia Ziehe, Kuratorin für Fotografie

Zitierempfehlung:

Theresia Ziehe (2015), Glücksmomente einer Fotokuratorin. Ilse Bings Fotografie New York – The Elevated and me.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/node/10670

X

X