Weder König David noch Cilly Kugelmann können das Problem lösen

Über die Schwierigkeit der Ausstellungsmacher*innen von „Welcome to Jerusalem“, dem Ideal der Gerechtigkeit gerecht zu werden

In der islamischen Tradition bzw. im Koran selbst wird die biblische Geschichte von David und Urija in einer von der Bibel abweichenden metaphorischen Form erzählt (Koran: Sure 38/21-25): Zwei Brüder kommen zu König David und fordern ihn auf, einen Streit zwischen ihnen zu entscheiden. Einer von beiden skizziert den Sachverhalt. Er erzählt David, dass sein Bruder 99 weibliche Schafe besitze, er selbst jedoch nur eines. Nun habe ihn sein Bruder unter Druck gesetzt, ihm dieses einzige weibliche Schaf auch noch zu überlassen.

Unmittelbar nach dieser knappen Schilderung verkündet David sein Urteil: Mit seinem Wunsch, das eine Schaf den 99 hinzufügen zu wollen, habe der eine Bruder dem anderen Unrecht getan. Der Richterspruch könnte der Erzählung ein Ende setzen, würde David nicht schlagartig von der Erkenntnis getroffen, dass sein Urteil ungerecht war. Er bereut seine Entscheidung zutiefst. Zahllose muslimische Korankommentatoren diskutierten über die plötzliche Wendung in der Erzählung. Eine Erklärung für die Bewertung des Urteils als ungerecht trotz des sich so eindeutig darstellenden Sachverhalts lautet, dass David sein Urteil gefällt habe, nachdem er nur einer Seite zugehört habe. Die Moral der Geschichte ist gemäß dieser Interpretation, dass man in Konflikten oder Streitfällen die Perspektiven und Argumente beider Seiten in seinem Handeln berücksichtigen muss.

Diesem universellen Ideal der Gerechtigkeit, das in der jüdischen wie auch in der islamischen Tradition von zentraler Bedeutung ist, hoffte das Museum in der Ausstellung Welcome to Jerusalem nahezukommen. Man hat sich darum bemüht, möglichst objektiv die unterschiedlichen Perspektiven sowohl sprachlich als auch inhaltlich und darstellerisch zu berücksichtigen. Mit vollem Bewusstsein der Brisanz des Themas – und lange vor Trumps überraschender Jerusalem-Erklärung – versuchte man diese ausgewogene Herangehensweise selbst in den kleinsten Details zu bewahren. Menschen aus verschiedenen Gruppen und Konfliktparteien sollten mit einbezogen werden, aktiv mitwirken und ihre Sichtweise präsentieren. So sprach man arabische sowie jüdische und andere Künstler*innen an und engagierte Guides mit unterschiedlichen Hintergründen.

Einige arabische Künstler*innen lehnten die Beteiligung ab, weil sie Angst davor hatten, in ihrem Umfeld unter den Verdacht der Normalisierung der Beziehungen mit Israel zu fallen. Nicht selten wurde gesagt: man wisse durchaus, dass es sich beim Jüdischen Museum Berlin um eine Bundeseinrichtung und damit um einen höchst erwünschten neutralen Boden und nicht um einen Vertreter des israelischen Staates mit einer Hidden Agenda handele. Der*die normale Bürger*in im arabischen Raum werde dies aber nicht verstehen. Für ihn*sie gebe es keine Trennung zwischen „jüdisch“, „israelisch“ und „zionistisch“. Eine Ausnahme stellte die palästinensische Künstlerin Mona Hatoum dar, die sich mit einem Objekt beteiligte.

Die Wahrnehmungen der Ausstellung und die Reaktionen darauf waren vielleicht nicht trotz des multiperspektivischen Charakters der Ausstellung, sondern gerade deswegen sehr kontrovers. Das ist nicht verwunderlich, denn alles, was sich auf diese Stadt bezieht, wird dichotomisch wahrgenommen.

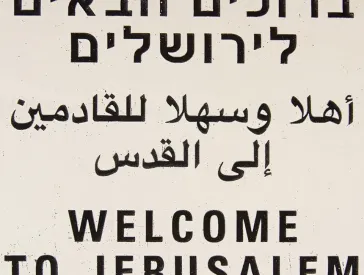

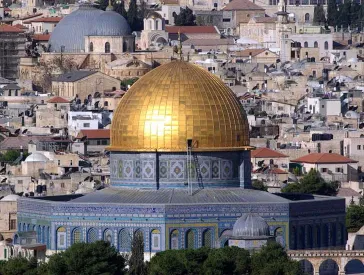

So kritisierten manche die Beteiligung Mona Hatoums, andere die verhältnismäßig geringere Präsenz arabischer Künstler*innen. Für einige waren die muslimischen und für andere die jüdischen Symbole überrepräsentiert. Die eine Seite fragte, warum die Menora auf dem Flyer abgebildet sei. Die andere kritisierte die dominante Darstellung der Kuppel des Felsendoms. Selbst das Willkommens-Schild, das einem Originalstraßenschild nachempfunden ist und als Blickfänger gedacht war, blieb von Kritik nicht verschont: Menschen mit arabischem Hintergrund monierten die Verwendung einer falschen Präposition im Arabischen und betrachteten sie als Übernahme einer wortwörtlichen Übersetzung aus dem Hebräischen, während anderen möglicherweise allein die Existenz der arabischen Schrift zu viel war. In dem grünen Hintergrund des Schildes sahen manche die Farbe des Propheten und damit ein islamisches Symbol. Von anderen wurde er als die Farbe der israelischen Autobahnschilder wahrgenommen und als ein Symbol des israelischen Staats interpretiert.

Wir wissen, dass absolute Objektivität der Darstellung unmöglich und die Subjektivität des*r Betrachter*in unendlich ist. Wie man sagt: Ein Kunstobjekt wird einmal geboren, wenn der*die Künstler*in es fertigstellt und erlebt jedes Mal eine neue Geburt in den Augen des*r jeweiligen Betrachter*in. Daher freuen wir uns auf jede neue Geburt unserer dargestellten Objekte. Egal, was Sie in dem Willkommens-Schild an der Fassade des Museums sehen, bleiben Sie nicht vor dem Schild stehen, sondern gehen Sie einfach rein und lassen Sie unsere Objekte neue Eindrücke bei Ihnen erwecken!

Walid Abd El Gawad, Islamwissenschaftler und W. Michael Blumenthal Fellow am Jüdischen Museum Berlin, stand dem Kurator*innen-Team von „Welcome to Jerusalem“ beratend zur Seite.

Zitierempfehlung:

Walid Abd El Gawad (2018), Weder König David noch Cilly Kugelmann können das Problem lösen. Über die Schwierigkeit der Ausstellungsmacher*innen von „Welcome to Jerusalem“, dem Ideal der Gerechtigkeit gerecht zu werden.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/node/6451

Blick hinter die Kulissen: Beiträge zur Ausstellung „Welcome to Jerusalem“ (9)

X

X