„Was auch immer du sehen willst – du kommst nach Jerusalem und findest es dort.“

Stimmen von Besucher*innen unserer Jerusalem-Ausstellung

Ich stehe im Gang am Ende der Ausstellung Welcome to Jerusalem und spreche nach dem Zufallsprinzip Besucher*innen an, die offen wirken für ein kurzes Gespräch über die Ausstellung.

War das hier gerade Ihr erster Besuch in Jerusalem?

Elke (um die 50 Jahre alt) aus Berlin war im Jahr 2000 in Jerusalem und hat in der Ausstellung einiges wiedererkannt. Norbert (69) aus Bremen war noch nie dort, aber die Ausstellung hat ihm Lust gemacht, „diesen ungeheuren Mischmasch aus Religionen und Völkern“

zu sehen.

Auf Marianna und Marta aus Italien, die gerade erstmals ‚in der Stadt waren‘, wirkt Jerusalem vor allem alt, international und reich an Geschichte. Lorenza (54), ebenfalls aus Italien, fand die Videoinstallationen in der Ausstellung besonders interessant, weil sie das moderne Jerusalem zeigen, in dem zugleich die Tradition anwesend ist. Alle drei würden wegen der politischen Lage derzeit aber keine reale Reise nach Jerusalem wagen.

Die Israelis Malka (58) und Shani (27) wohnen bei Tel Aviv, kennen aber auch Jerusalem recht gut, Jonny (27) und Nora (24) haben sogar dort geheiratet.

Entspricht das Jerusalembild in der Ausstellung Ihrem Jerusalem?

Shani: „Ja, weil man in den gezeigten Videos alle möglichen Leute aus Jerusalem sieht und in der Ausstellung alles, was Jerusalem repräsentiert.“

Jonny: „Ja und Nein. Wie die Ausstellung all die Religionen, verschiedenen Sichtweisen und politischen Klassen, all die unterschiedlichen Arten von Leuten zeigt – ja, das ist eindeutig richtig so. Und sie zeigt auch Jerusalems geschichtlichen Hintergrund. Aber bei dem Film über den Konflikt fand ich, dass er nur die Ereignisse zeigt, aber nicht, was dazu geführt hat und warum.“

Elke findet die Ausstellung beim Thema Religion „insgesamt schon ausgewogen. Die Ausstellung ist sicherlich mehr der jüdischen Tradition zugewandt, aber es gibt in jedem Raum eine Ausgewogenheit zwischen den Religionen. Und natürlich darf in einem jüdischen Museum der Schwerpunkt auf dem Judentum liegen. Dass auch die anderen zu Worte kommen, finde ich schon sehr in Ordnung.“

X

X

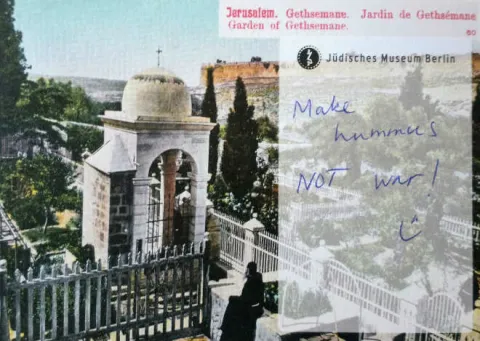

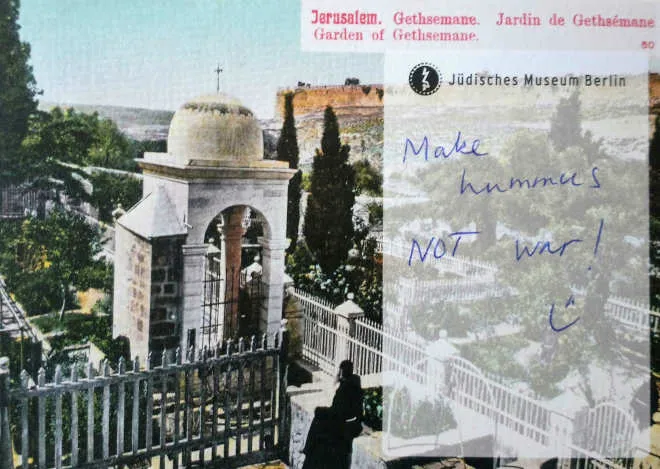

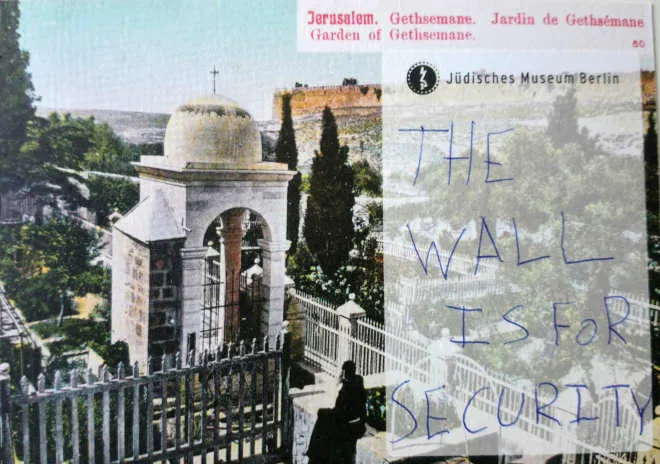

Besucher*innen können einen Kommentar, einen Gruß oder anderes auf eine Postkarte schreiben und sie an einer Wand am Ende der Ausstellung hinterlassen, auf der „nächstes Jahr in Jerusalem“ steht; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Foto: Mirjam Bitter.

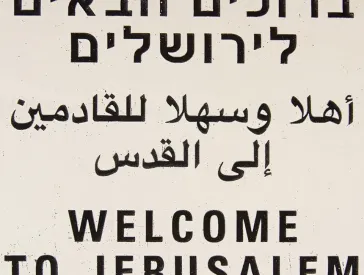

Raumansicht der Ausstellung Welcome to Jerusalem; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Foto: Yves Sucksdorff.

Was verbindet Sie mit Jerusalem?

Da wir israelische Stimmen zu dieser Frage bereits in einem Online-Beitrag präsentiert haben, stelle ich die Frage vor allem den Nicht-Israelis. Die Italienerinnen haben keine persönliche Verbindung zu Jerusalem.

Elkes persönliche Verbindung zu Jerusalem hat mit ihrer Religion zu tun. „Ich bin studierte christliche Theologin. Ich unterrichte Religion an einer staatlichen Schule in Berlin. Bei meinem Besuch wollte ich mir Stätten ansehen, die etwas mit der Bibel zu tun haben, mit dem Glauben und, natürlich, mit dem Judentum. Dementsprechend waren auch hier in der Ausstellung einige Sachen, die für mich interessant waren, die ich aber auch schon kannte.“

Während für sie Jerusalem also „von der religiösen Seite her sehr interessant“

ist, findet sie die dortigen „vielen Auseinandersetzungen schon bedrückend“

.

Norberts Bezug zu Jerusalem ist noch indirekter: „Ich bin Schauspieler. Ich hab mal den Shylock gespielt. Das war eine sehr intensive Auseinandersetzung mit Judentum, auch im Zusammenhang mit Christentum und dem Problem des Stückes (Der Kaufmann von Venedig von William Shakespeare). Ich merke immer wieder, dass mich das zutiefst interessiert, wie sich diese Religionen zueinander, gegeneinander und miteinander behaupten, mit ihren so klaren Meinungen davon, wie die Welt ist. Das ist eine komplizierte Geschichte.“

Ein weiterer Bezugspunkt für Norbert ist die deutsche Geschichte (womit er unter den deutschen Ausstellungsbesucher*innen vermutlich nicht allein ist): „Ich musste, obwohl die Schoa in der Ausstellung gar nicht direkt abgehandelt wird, ständig an diesen Wahnsinn denken, der durch den Holocaust entstanden ist; und was das an Zuspitzung innerhalb des Nahostkonfliktes produziert hat. Das ist mir ständig im Kopf rumgegangen, dass ‚wir‘ Deutsche einen riesigen Anteil an diesem nicht lösbaren Konflikt haben.“

Was waren Ihre Lieblingsräume in der Ausstellung?

Jonny: „Ich mochte den christlichen Raum. Der war sehr schön dekoriert.“

Ich: „Die Kruzifixe?“

Jonny: „Ja.“

Malka: „Ich fand alles schön.“

Shani: „Ja, weil jeder Raum, den du betrittst, eine andere Geschichte erzählt.“

Malka: „Und wir kennen das. Wir haben es in der realen Stadt gesehen und können es hier wiedererkennen.“

Marianna und Marta: „Der letzte Raum mit den Postkarten. Und die Klagemauer. Ich kannte sie schon, aber in der Ausstellung hat sie mich trotzdem beeindruckt.“

Norbert hat der „Raum mit den Konflikten“

besonders gefallen, „weil da sehr klar mal wieder benannt wird, was ein Teil des Problems ist.“

Wie haben Sie den Raum wahrgenommen, der sich mit dem Nahostkonflikt beschäftigt?

Interpretiert hat Norbert den Raum „wie in der Lessing’schen Ringparabel: Was macht man, wenn einer behauptet, ich bin derjenige dem es gehört, und nicht, was Lessing sagt, alle drei haben Recht. Dieses Problem ist für mich in dem Raum nochmal sehr deutlich geworden – was macht man, wenn zwei Religionen oder auch politischen Systemen dasselbe Land versprochen ist?“

X

X

Der Raum Die Reise nach Jerusalem ist dem Thema Pilgern gewidmet, dabei geht es nicht allein, aber doch in erster Linie um christliche Pilgerschaft; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Foto: Yves Sucksdorff.

Jonny und Nora kritisieren den Film, der im Konfliktraum gezeigt wird:

Jonny: „Wenn im Film vorkommt, dass Israel in den Krieg zieht, zeigt er nicht, dass Israel vorher tagtäglich von seinen umliegenden fünf Feinden angegriffen wurde. Ich befürchte, wenn Außenstehende den Film sehen, werden sie denken ‚Oh, die Israelis haben aber eine starke Armee, sie sind weit überlegen, dominieren alles und versuchen die Palästinenser*innen umzubringen‘, was überhaupt nicht so ist, wenn man wirklich nach Jerusalem fährt.“

Nora: „Der Film zeigt nur die Gewalt und nicht das Gute an Jerusalem: zum Beispiel, dass Araber*innen hier die höchste Lebensqualität im gesamten Nahen Osten haben oder dass die jüdische Bevölkerung in die arabischen Gebiete geht und dort einkauft und umgekehrt die arabische Bevölkerung auch in die jüdischen Gebiete kommt. Es gibt auch friedliche Koexistenz, weißt du.“

Elke dagegen findet, die Darstellung des Konfliktes in der Ausstellung sei eher Israel zugewandt, in ihrer Wahrnehmung befürworte die Ausstellung die Errichtung des Staates Israel und spreche sich nicht dafür aus, mit den Palästinenser*innen zu teilen. „Es kommen zwar auch Punkte der Palästinenser zu Wort, aber weniger. Der Konflikt wird in einem eigenen Raum dargestellt, aber sonst wird nicht so viel darauf eingegangen. Ich persönlich stehe beim Nahostkonflikt nicht hinter Israel, sondern eher hinter den anderen Gruppen. Die Palästinenser lebten dort zuerst und ich finde, wie Juden, das jüdische Volk, sich dort benehmen ist nicht adäquat gegenüber dem alten Volk. Es muss dringend eine Lösung gefunden werden, die ich aber nicht sehe, weil schon so viel gegenseitiger Hass aufgebaut wurde.“

X

X

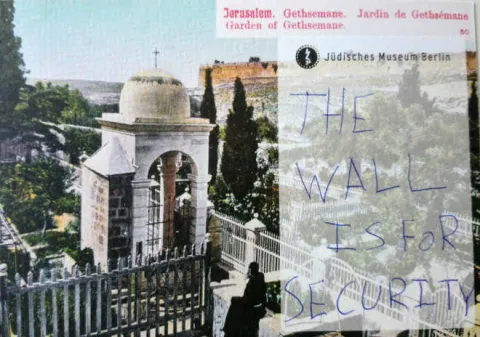

An den Postkarten lässt sich ablesen, dass Besucher*innen mit sehr unterschiedlichen Meinungen zum Nahostkonflikt die Ausstellung besuchen; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Foto: Mirjam Bitter.

Lorenza schlägt sich nicht ganz so eindeutig auf eine Seite, reflektiert aber zugleich ihre begrenzte Sicht und eigene Unausgewogenheiten:

„Die Ausstellung hat meine Meinung nicht verändert, die grundsätzlich gegen kriegerische Auseinandersetzungen ist. Ich verstehe wirklich nicht, was der Bau von Mauern bringen soll oder die Entscheidung, dass eine hierbleiben kann, die andere aber nicht. Auch wenn es sich um Auseinandersetzungen mit langer Geschichte handelt. Wir können vielleicht darüber streiten, was wir für die richtige Religion halten, aber in einer Diskussion und einer Debatte über Prinzipien. Doch jemanden umzubringen, nur weil er oder sie anders denkt als du, ist so weit entfernt von den Prinzipien jeglicher Religion. Mag sein, dass ich da eine sehr einfache Sicht auf die Dinge habe, aber wenn man sich die Lage anschaut, ist es wirklich ein Jammer. Ich glaube, es gibt viele echt nette Menschen in Israel und überall. Aber immer, wenn ich im Fernsehen Palästinenser*innen sehe, die ohne Wasser und Elektrizität leben, verstehe ich nicht warum. Doch mehr als über Israel muss ich mich über den Rest der Welt beklagen, weil auch wir den Stand der Dinge zulassen. Mir scheinen die Kräfte zwischen den Israelis und den Palästinensern so unausgewogen, dass natürlich Israel versuchen sollte, eine Lösung zu finden. Wahrscheinlich habe ich eine begrenzte Sicht und habe für mich schon beschlossen, dass der israelische Staat irgendwie seine Meinung ändern sollte. Insofern bin ich vielleicht selbst unausgewogen zugunsten der Palästinenser*innen. Ich weiß, dass auch sie etwas falsch gemacht haben. Dazu gehört unter anderem der Terrorismus. Sie sind nicht ‚die Guten‘. Aber mir scheint, sie leiden mehr und haben weniger Unterstützung als Israel.“

Nachdem ich so unterschiedliche Meinungen zum Konfliktraum gehört habe, frage ich bei Malka und Shani erstaunt nach, ob sie etwa nichts daran auszusetzen haben:

X

X

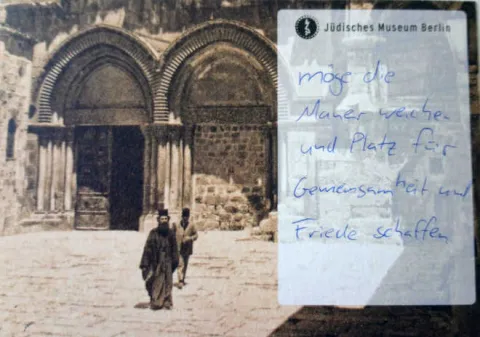

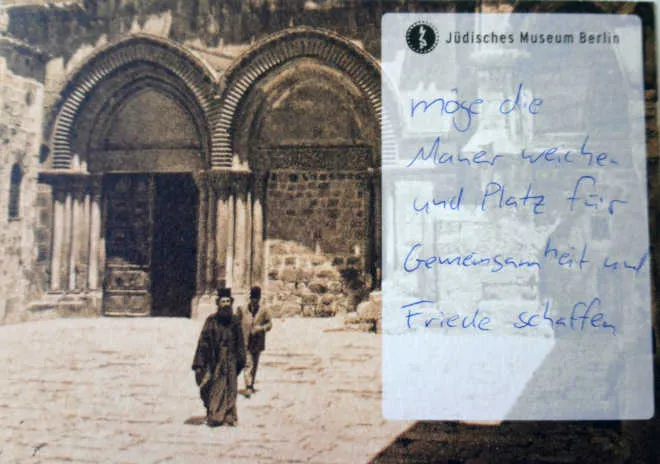

Auf dieser Postkarte hinterließen Besucher*innen den Wunsch: „Möge die Mauer weichen und Platz für Gemeinsamkeit und Friede schaffen“; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Foto: Mirjam Bitter.

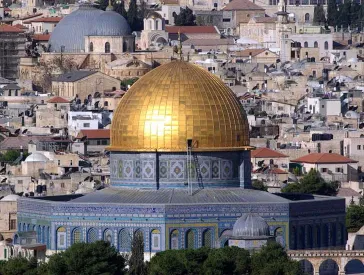

Momentaufnahme aus dem Film im Ausstellungsraum, der sich mit dem Konflikt beschäftigt; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Foto: Yves Sucksdorff.

Malka: „Hmm…“

Shani: „Es ist schon kompliziert genug.“

Malka: „Wir leben an einem schwierigen Ort mit schwierigen Leuten. Und wir sind daran gewöhnt.“

Shani: „Es ist sehr schwer, alles in einem einzigen Raum zu sagen. Es ist halt nicht Schwarz-Weiß, weißt du.“

Malka: „Es ist unmöglich, das alles abzudecken. Du musst es erleben. Jeden Tag. Einen Film darüber zu sehen … ist eben nur ein Film, nicht das wirkliche Leben.“

Shani: „Wir müssen die Lage auch in den Medien bekämpfen. Es geht darum, was die Welt von uns denkt. Das ist ein großes Problem. Und diese Ausstellung ist gut, weil sie auch die andere Seite zeigt. Sie zeigt, dass es bei uns auch Muslime und Christen und Juden gibt, die friedlich zusammenleben, manchmal in derselben Straße oder im selben Gebäude. Und das ist gut. Aber die Welt sieht nur die Palästinenser in Gaza.“

Malka: „Es ist sehr schwer. Und es ist auch für sie schwer. Nicht nur für die Israelis. Alle wollen Frieden. Wir wollen Frieden.“

Was nehme ich selbst von diesen Gesprächen mit Besucher*innen mit?

Mich interessierte, wie Besucher*innen die Ausstellung und die Thematisierung des Nahostkonflikts darin wahrnehmen – wirkt die Ausstellung eher pro-israelisch oder pro-palestinensisch oder neutral? Ich habe ganz unterschiedliche Antworten bekommen.

Lorenza: „Ich hatte nicht das Gefühl, dass die Ausstellung gegen oder für etwas war. Ehrlich. Es ging vor allem um israelische Geschichte und Kultur, aber ich sehe auch die Anstrengung, nicht zu unausgewogen zu sein. Aber auch diese Einschätzung fußt natürlich wieder auf meinen Vorannahmen und meinem Vorwissen.“

Wie Lorenza komme ich zu dem Schluss, dass die Wahrnehmung der Ausstellung stark von unseren Vorannahmen und Haltungen beeinflusst ist. So sagen die von mir eingefangenen Stimmen letztlich mehr über die jeweiligen Besucher*innen als über die Ausstellung aus. Und was Malka über die reale Stadt sagte, mag so vielleicht auch für Jerusalem in Berlin gelten: „Ich glaube, Jerusalem repräsentiert die Welt. Da gibt es so viele unterschiedliche Leute, Essen, Kleidungsstile, Kulturen. Was auch immer du sehen willst – du kommst nach Jerusalem und findest es dort.“

Florian Schmeling war schon zweimal in Jerusalem und ist sich bewusst, dass auch er keine ‚objektive‘ Sicht auf die Ausstellung und erst recht nicht auf den Konflikt hat – ebenso wenig wie Web-Redakteurin Mirjam Bitter, die seine Einzel-Interviews zu diesem Text arrangiert hat.

Zitierempfehlung:

Florian Schmeling (2018), „Was auch immer du sehen willst – du kommst nach Jerusalem und findest es dort.“. Stimmen von Besucher*innen unserer Jerusalem-Ausstellung.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/node/6441

Blick hinter die Kulissen: Beiträge zur Ausstellung „Welcome to Jerusalem“ (9)