Bäume, Obst und ein Hauch von New Age

Israelische Traditionen zu Tu bi-schwat

Die Bedeutung von Feiertagen zeigt sich nicht zuletzt daran, ob man ein paar Tage frei von Schule und Arbeit bekommt. So auch in Israel. An diesem zugegeben nicht unbedingt religiösen Kriterium scheitert zwar Tu bi-schwat, das „Neujahrsfest der Bäume“. Israelische Schüler aber dürfen den Tag zumeist in der Natur verbringen. Denn an Tu bi-schwat unternimmt man gewöhnlich einen Ausflug, um Bäume anzupflanzen. Die meisten freuen sich darauf; für einige aber – und zu diesen zählte ich als Schüler selbst – ist es eine Erleichterung, wenn die Baumfürsorge durch eine besondere Form des Beisammenseins im behüteten Klassenzimmer ersetzt wird.

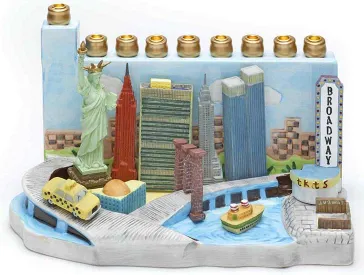

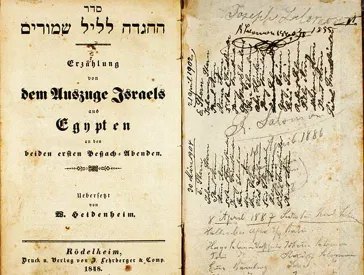

Tatsächlich wird in den letzten fünfzehn Jahren die Tradition der Anpflanzung, die bereits von der zionistischen Bewegung gepflegt wurde, zunehmend von einer neuen ergänzt – dem Seder Tu bi-schwat, dessen Name auf den Seder (hebr.: Ordnung) zu Beginn des Pessach-Fests anspielt und der, wie ich hörte mittlerweile auch in Deutschland begangen wird. Ebenso wie an jenem Abend, genießt man auch am Seder Tu bi-schwat die Gemeinschaft, indem man zusammen isst, trinkt, singt und einen Text liest: die Tu bi-schwat-Haggada (in Anlehnung an die Pessach-Haggada).

Erdacht wurde diese Übertragung des ritualisierten Seder-Abends auf das Neujahrsfest der Bäume bereits im 17. Jahrhundert von dem berühmten Kabbalisten Isaac Luria, aber erst in den 1950er Jahren fand der Seder Tu bi-schwat auch in säkularen Kreisen Israels Anklang: Die Kibbuzim begannen, das „Neujahrsfest der Bäume“ mit Texten und Gesang zu feiern, und Mitte der neunziger Jahre wurde der Seder Tu bi-schwat richtiggehend populär. Anhänger der Ökologie-Bewegung entdeckten das Fest für sich und interpretierten es als einen Tag der Natur, an dem es über ein neues Verhältnis von Mensch und Umwelt nachzudenken gilt. Für mich hat die Kombination aus Kabbala und Naturliebe, die in den Seder Tu bi-schwat einging, stets ein wenig den Geschmack von New Age gehabt.

Während der Seder zu Beginn des Pessach-Fests auf tradierten Texten, Gesängen und Bräuchen beruht, wird an Tu bi-schwat viel improvisiert. Den Jahreszeitenwechsel symbolisiert man zum Beispiel mit vier Gläsern Weiß- und Rotwein – vermischt. Besonders köstlich schmeckt das leider nicht. Im Unterschied zum strengen Protokoll von Pessach aber verleiht dieses Mischmasch dem Abend ein amüsantes Ambiente.

Gleiches gilt auch für Text und Gesang: Es werden nicht alte Choräle, sondern bekannte, moderne Lieder gesungen, die Assoziationen aus dem unmittelbaren Alltag hervorrufen. Auch das Essen ist leichter: An Pessach isst man eine etwas schwer bekömmliche Kombination verschiedener Speisen wie etwa Fleisch, Ei und ungesäuertes Brot, beim Seder Tu bi-schwat hingegen für Israel typisches Obst und Gemüse zusammen mit Trockenfrüchten. Zu den üblichen Rosinen, Aprikosen und Feigen sind in den letzten Jahren tropische Früchte wie Ananas, Kokos oder Papaya hinzugekommen.

Und die Anpflanzungen? Auch sie spiegeln die Zeiten. Eine Bekannte aus einem Kibbuz hat mir erzählt, wie sie und ihre Klassenkameraden vor Jahren an Tu bi-schwat einen „Garten des Friedens“ anbauen sollten: Die Kids nahmen Reißaus, die Bäume hat der arabische Gärtner alleine angepflanzt.

Avner Ofrath, Medien

Zitierempfehlung:

Avner Ofrath (2013), Bäume, Obst und ein Hauch von New Age. Israelische Traditionen zu Tu bi-schwat.

URL: www.jmberlin.de/node/6211

Feiertage: Alte Riten, neue Bräuche (19)

X

X

X

X

X

X